FEATURES|THEMES|Women

Reflections from the 14th Sakyadhita International Conference: Nurturing the Theravada Bhikkhuni Sangha

Photo by Olivier Adam

Photo by Olivier AdamAt a Sakyadhita conference, you are in the company of a lot of “firsts” in Buddhism. You might find yourself sharing a meal with one of the first bhikkhunis ordained in the Theravada tradition in Thailand or Indonesia or Vietnam. Or sitting on a bus next to one of the first Western women ordained in the Tibetan or Korean tradition decades ago when such a thing was a real rarity. Or having tea with one of the first scholars to document the life and work of this or that under-studied, eminent woman in Buddhist history. Indeed, amazing, pioneering women (and men) from various Buddhist traditions were present in force at the 14th Sakyadhita International Conference in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, from 23–30 June this year, which was attended by over 1,000 monastic and lay participants from 40 countries.

The latest in a series of conferences organized every two years since 1987 by the Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women, this year’s conference was themed “Compassion and Social Justice.” One of the most important social justice issues in Buddhism’s own backyard, of course, is the lack of equal opportunity for ordination and Buddhist education for women. Although many other important matters were discussed at the conference, this article will report on this topic, and particularly the situation of Theravada nuns, while drawing on experiences shared by other traditions.

Since the early years of Sakyadhita, one key area where energy has been focused is opening the way for women to become fully ordained Buddhist nuns (Pali: bhikkhunis; Skt: bhikshunis) in the Theravada tradition, where the lineage had been discontinued, and in Vajrayana, where it had never been established. While more gradual progress is being made in the latter, in the Theravada tradition the revival of full bhikkhuni ordination has been ongoing for almost 30 years. With the first wave starting in the 1980s, it has become more solidly established since the large-scale international bhikkhuni ordination held in Bodh Gaya in 1998.

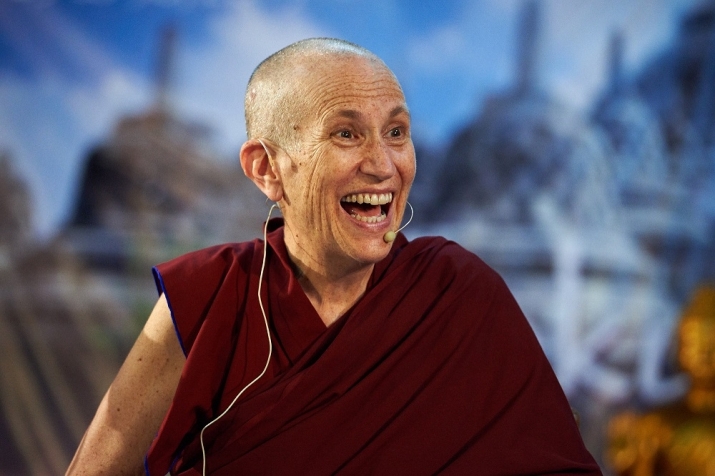

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo. Photo by Olivier Adam

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo. Photo by Olivier AdamThe question is no longer, “Can we revive the Theravada bhikkhuni sangha?” Already done. Those still debating that point are a tad out of date. Theravada bhikkhuni sanghas exist and are growing in different countries from South Asia to Southeast Asia, Australia, Europe, and America. Rather, the salient question now is, “How can the revived bhikkhuni sangha be nurtured and supported so that it takes firm root?”

Nonetheless, before discussing countries where the Theravada bhikkhuni sangha is expanding, it is important to highlight that there are still places where it is struggling to emerge, like Myanmar. One conference participant was a Burmese bhikkhuni ordained and living in Sri Lanka. As the only Burmese woman, Saccavadi Bhikkhuni, previously to have ordained as a Theravada bhikkhuni and returned to Myanmar was imprisoned in 2005—the trauma of which led to her eventual disrobing—it is courageous indeed for this new-generation Burmese bhikkhuni to have taken higher ordination earlier this year. Perhaps one day she might return to bring the bhikkhuni lineage to Myanmar.

In neighboring Bangladesh, also, there are no Theravada bhikkhunis yet, but a small group of brave women are blazing the trail by taking samaneri (novice) ordination. Sakyadhita sponsored their attendance at the conference, and their story was presented in a paper written by a sympathetic Bangladeshi bhikkhu. Led by Samaneri Gautami* who, as Runa Barua, had already been a well-respected lay vipassana teacher for 15 years, the initial core group was ordained in November 2011 and has established a samaneri community that has now grown to eight nuns. While they have met with support from some bhikkhus and laypeople in Bangladesh, they have also had to contend with strong opposition.

At one point, a group of senior bhikkhus told Samaneri Gautami to disrobe. Her response? She pointed to copies of the Bhikkhuni Vibhanga, part of the Vinaya (monastic discipline) section of the Tipitika, which had been translated into Bengali (at the behest of a supportive bhikkhu, actually), and said, “If you ban these books, only then will I disrobe.” The existence of the Bhikkhuni Vibhanga, consisting of the monastic disciplinary rules particular to bhikkhunis and their explanations, attests to the fact that the bhikkhuni sangha was established by the Buddha and was an essential part of his dispensation. It delineates the special way of life of a bhikkhuni, full ordination being designed by the Buddha as the vehicle most conducive to full enlightenment. If the bhikkhus could not deny that these texts were an authentic part of the Buddha's teachings as preserved in the Pali canon, Samaneri Gautami saw no grounds for their claim that her ordination as a novice—the precursor of a bhikkhuni—was illegitimate and for their demands that she disrobe. In person, Samaneri Gautami’s steady gaze reveals both an imperturbable calm and a steely strength which belies her youthful appearance and bodes well for the possibility of a future bhikkhuni sangha in Bangladesh.

Bhikshunis from Korea and elsewhere. Photo by Olivier Adam

Bhikshunis from Korea and elsewhere. Photo by Olivier AdamStarting a bhikkhuni sangha, though not easy, is only the first step, however. The next crucial issue to grapple with is how a new bhikkhuni sangha is to be educated and trained. This is one of the main challenges facing the Theravada bhikkhuni sanghas in countries where they have been around for 10–20 years. The question came up again and again during the conference, in panel, workshop, and informal discussions: how to provide solid monastic training—especially in Vinaya, the foundation of bhikkhuni life—to the first generations of Theravada bhikkhunis? Such training is essential for fledgling nuns’ communities worldwide, Theravada or otherwise, to grow and flourish for a long time to come rather than sputter out in their infancy.

In proposing possible solutions, conference participants drew on one of the great strengths of Sakyadhita—that of providing a forum for cross-sectarian dialogue, assistance, and linkages. On the last day, a special focus group discussed the possibility of launching programs of international exchanges for Buddhist nuns. One proposal was for nuns in the Theravada or Vajrayana tradition to spend from three to six months in a nunnery in Korea or Taiwan, where the long-standing Mahayana bhikshuni sanghas have well-established training systems, in order to learn about monastic training and community organization. Korean bhikshunis at the meeting generously offered to extend their hospitality and assistance, and a working group coordinated by Sakyadhita vice-president and Korean national chapter head Dr. Eun-so Cho agreed to carry the discussions further post-conference.

Front, from left - Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, Karma Lekshe Tsomo; back, from left - Dr. Eun-so Cho, Christine Chang (former president of Sakyadhita), Lien Bui (treasurer of Sakyadhita). Photo by Olivier Adam

Front, from left - Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, Karma Lekshe Tsomo; back, from left - Dr. Eun-so Cho, Christine Chang (former president of Sakyadhita), Lien Bui (treasurer of Sakyadhita). Photo by Olivier AdamAnother idea proposed was to leverage the knowledge and experience of senior nuns at the next Sakyadhita gathering to offer cross-sectarian Vinaya workshops where participants could learn about different perspectives on the Vinaya and ways of practicing monastic discipline in different Buddhist traditions. In a conversation with American nun Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron, I learned how this cross-sectarian Vinaya instruction can work in practice. At Sravasti Abbey, the monastery she has founded in Washington State for training Western monastics, the nuns follow the Tibetan tradition but study and practice the Dharmaguptaka bhikshuni Vinaya, which is prevalent in Taiwan, China, Korea, and Vietnam and is the lineage in which Thubten Chodron and her students received bhikshuni ordination. While they receive instruction from teachers such as the Taiwanese Vinaya master Bhikshuni Wu-Yin, they are also adapting their Vinaya practice to American circumstances.

Thubten Chodron. Photo by Olivier Adam

Thubten Chodron. Photo by Olivier AdamIndeed, as Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, president of Sakyadhita, notes, monastics must live within a certain culture and the Vinaya has to be interpreted and practiced in a way that fits in with that culture. While cross-sectarian exchange can be beneficial in many ways, she points out that what nuns learn of the monastic lifestyle from a different tradition must ultimately be filtered back and adapted into their own cultural context.

In order for Theravada bhikkhunis to obtain training suitable for their own tradition, the other possible strategy is to look to their bhikkhu brothers for teaching. This is, of course, the classic method used time and again throughout history to enable new bhikkhuni sanghas to become well established. Ever since the time of the Buddha, when the bhikkhuni sangha was just starting out, the Buddha had the bhikkhus teach the bhikkhunis the Dhamma and Vinaya, including how to recite the Patimokkha (monastic rules) and perform community transactions (sanghakamma), until the bhikkhuni sangha was mature enough to do so themselves and also to train other bhikkhunis. Even when the bhikkhuni sangha was thriving bhikkhus continued to play a role in their education, with there being a Vinaya rule requiring bhikkhunis to request a teaching from the bhikkhus every half-month.

Thubten Chodron (left) wth Karma Lekshe Tsomo. Photo by Olivier Adam

Thubten Chodron (left) wth Karma Lekshe Tsomo. Photo by Olivier AdamFortunately, in contemporary times, there are still bhikkhus who are assisting bhikkhunis, even while senior monks at the top of the monastic administrative hierarchies—instituted in the modern era in countries like Sri Lanka and Thailand—remain opposed to Theravada bhikkhuni ordination. Among the handful of bhikkhus who attended the conference (in this case the minority at a Buddhist gathering!) was Ajahn Brahm, famous for supporting the first ordination of Theravada bhikkhunis in Australia in 2009, which led to his disenfranchisement from a Thailand-based network of forest monks. In his talk, he said, “I feel my life is not complete as a bhikkhu if I don’t help to realize the Buddha’s intention [to establish the four-fold Buddhist assembly.] The Buddha would have asked [us] to help get more bhikkhunis established in this world.

“It’s not just ordination. If you ordain someone you have to look after them. It’s like having a baby. You don’t just have a baby and that’s the end of it. You’ve got to nurture the baby, send it to school, train it, give it good facilities so it can grow. It’s like planting a tree. You’ve got to protect it, nurture it, water it, even fertilize it, and only when that tree is very, very strong and independent can you walk away and leave it alone. So it’s really important to nurture bhikkhunis. That’s one of my jobs. If there is something you can do, then please do it.” Hopefully more bhikkhus will resonate with this view and feel a sense of duty to actively help train bhikkhunis. If they wait for the top-most bhikkhu sangha elders to officially recognize bhikkhunis first before doing anything, it could well be too late.

Ajahn Brahm. Photo by Olivier Adam

Ajahn Brahm. Photo by Olivier AdamHow a strong and independent bhikkhuni/bhikshuni sangha can grow with initial help from bhikkhus/bhikshus can be seen in the case of modern Korea. A wonderful documentary was shown at the conference on Myeong Seong Sunim, one of Korean Buddhism’s luminaries. Ordained as a novice nun in 1952 in the midst of the Korean War, she was part of the generation of nuns that helped to rebuild nunneries and nuns’ educational systems from next to nothing, after being ravaged by decades-long Japanese occupation, World War II, and the Korean War. As a young nun, when education for nuns was still very limited, Myeong Seong studied under many eminent bhikshu masters, until her bhikshu teacher ceded his Dharma seat to her and authorized her to teach in her own right. She chose to dedicate herself to the development of self-sufficient education systems for nuns, and under her leadership, Un Mun Sa Monastic College became one of the leading training centers for Korean bhikshunis. It has graduated over 1,500 nuns in the past 50 years and produced many accomplished teachers.

What the Korean bhikshunis managed to build up in just half a century shines a beacon of hope. Indeed, the inspiring examples set and generous offers of assistance by the well-established Mahayana bhikshunis and Theravada bhikkhus are very uplifting. It is also heartening to see how more senior Theravada bhikkhunis are reaching out to help their younger sisters, such as the organization of training for Indian bhikkhunis supported by Sri Lankan, Vietnamese, and Thai theri bhikkhunis (bhikkhunis ordained for ten or more vassas, or rains retreats). Still, it will no doubt take a lot more hard work to build up a solid monastic education and stable monasteries for Theravada bhikkhunis around the world.

Before feeling too daunted, it’s good to remember a delightful moment from the conference. Ayya Santini Bhikkhuni, when asked how she dealt with the challenges she faced as one of the pioneers of the Theravada bhikkhuni sangha in Indonesia, smiled and quipped: “Well, we didn’t ordain as bhikkhunis to relax!”

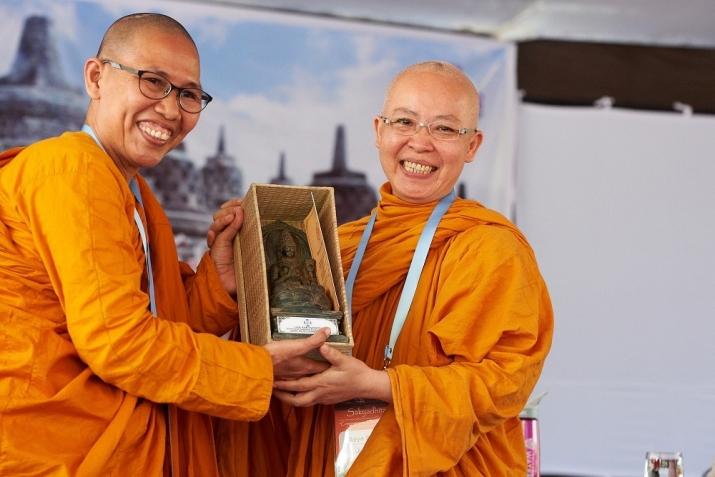

Ayya Santini (right) with Ayya Nyana Pundarika Bhikkhuni (organzing committee member). Photo by Olivier Adam

Ayya Santini (right) with Ayya Nyana Pundarika Bhikkhuni (organzing committee member). Photo by Olivier AdamAs the “firsts” in the modern Theravada bhikkhuni sanghas are joined by burgeoning ranks of “seconds,” “thirds,” and now “thousandths,” the job at hand is for the international four-fold Buddhist community to work together to support their training, development, and growth. For, as was stated again and again by conference participants, only when all four pillars of Buddhist society—bhikkhus, bhikkhunis, lay male devotees, and lay female devotees—are firmly established can the Buddhasasana (Buddha’s dispensation) thrive and be a force for compassion and social justice in the world.

Munissara Bhikkhuni was born to Thai parents in Manila, Philippines, in 1978. She holds a BA in history from Harvard University and an MA in Southeast Asian Studies from Chulalongkorn University. After working as a researcher, journalist, university lecturer, and teacher at a Buddhist school, she went forth as a samaneri in July 2009 and took bhikkhuni ordination in March 2012. She is currently based at Suddhacitta Bhikkhuni Arama in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

* See The Journey of Women Going Forth into the Bhikkhuni Order in Bangladesh: An Interview with Samaneri Gautami, Part 1 (Buddhistdoor Global)