FEATURES|COLUMNS|Creativity and Contemplation

Resiliency: Releasing Trauma through Embodied Art

Les Dessins du 14 © Fiorenza Menini 14 July 2016

Les Dessins du 14 © Fiorenza Menini 14 July 2016Our humanity is not innate but acquired. We need to recreate and hone it every day. We are nothing without it. We may not be able to stop the violence that seems to be sweeping over us, nor the murderous beliefs [of extremists], but we are in charge of our own humanity, we are responsible for it and we can act to renew it every day.*

In the late summer of 2014, I traveled from Barcelona by train through coastal France over to Rome, visiting dear friends along the way. I took a room in Nice with an artist with whom I happened to share a mutual friend. Fiorenza Menini was my consummate host, who took me to the market to enjoy socca (the local chickpea flour crêpe) and fresh produce. She also shared her artwork with me, both beautiful and intriguing. A successful artist, she shows her photography and performance art in Paris, in the US, and around Europe. I found in Menini a kindred spirit and a new friend. An artist myself, I walked the Promenade des Anglais, taking photographs and enjoying views of the sea.

Two years later, during the annual Bastille Day fireworks celebration, a brutal and senseless truck attack took place on the Promenade. I reached out to Menini and learned about the trauma she had endured being present that night. She had had to run to avoid being struck by the truck barreling toward her, which killed and injured many that awful night. I understood that though she had been relatively unharmed physically, she was left deeply affected: emotionally, psychologically, and physiologically. In deep shock, Menini was seen in the hospital several times after the attack but did not find the necessary help; on the contrary, she felt it only reinforced the trauma rather than alleviating it. Housebound with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for some weeks, and unable to find relief, she faced a wall of incapacity on the part of the medical establishment, and felt her friends pulling away, not knowing how to relate to her state.

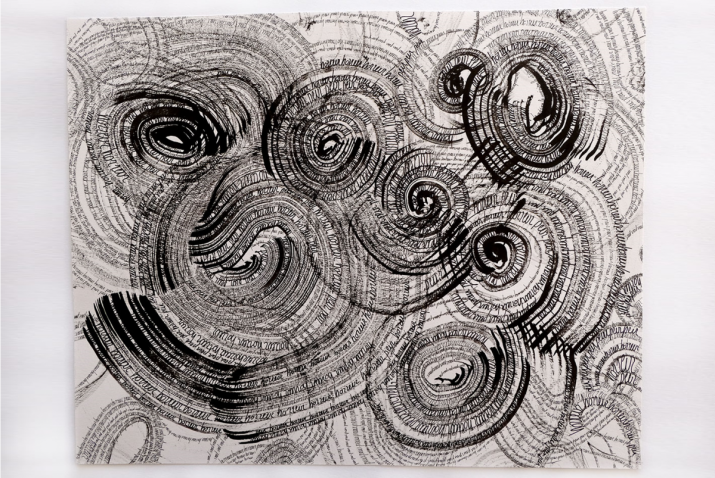

In drawing, she found a path back to humanity and a way to metabolize her felt-sense experiences, knotted in the body. With an urgent need to heal through methods unrelated to the intellect, she laid out paper and ink which she accessed during many sleepless nights. Menini felt divergent sensations passing through her, nonverbal feelings and impressions needing release. Through an instinctive, somatic experience of putting ink directly to paper, using her hands, fingers, and forearms, the embodied trauma began to find outlet. This somatic, immersive method of using large body movements as a human brush were a more immediate and visceral way to express held trauma.

Peur (Fear), detail © Fiorenza Menini 2016

Peur (Fear), detail © Fiorenza Menini 2016Reflecting on these spontaneous works later, Menini saw there were discrete groups of drawings. For example, Fears are drawings made in ink with prints of her fingers, phalanges, or fingertips. Not using a brush or pen, but needing a more direct approach, she would ink and print her skin on paper. The Fears resemble roots or tubers that come out of the ground. She eradicates these roots, unearthing the black, unpredictable forms with fearful words appearing either inside or outside the drawn forms, recalling her feeling of dense terror, and expressing it instinctively, often with large and sudden strokes.

Impacts are large format ink drawings with confused, violent, exploding black lines. Though one cannot really distinguish a truck, it is there. Menini thinks these are among the first drawings of that period but doesn’t fully remember. We do not discern bodies there—only energies and solid forms—great powers that collide and seem to vibrate through existence. With each drawing, she exorcised a stage, a memory, or a sensation, trying to distill it from herself and place it onto the paper.

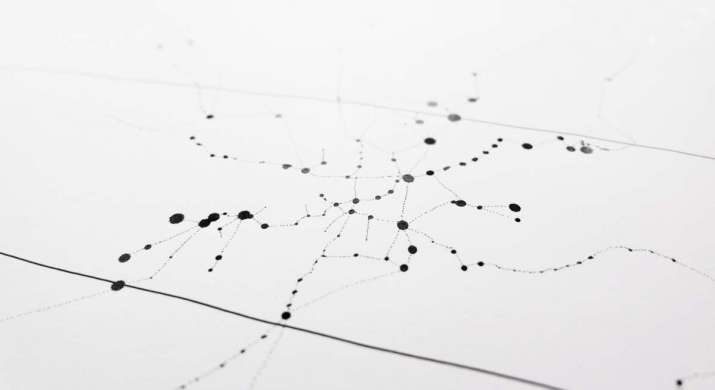

The Wandering Souls set is very special for Menini as they were done at a later stage of coping and provided a deeply restorative, healing process. In contrast to the drawings where her body would release large erratic gestures, Wandering Souls required her concentration, stillness, and patience. Each spot on the big sheets of paper, red or black, corresponds to ink exploded onto the sheet. Each represents a lost soul that she connects to another with (a line of) small dots. It was vital for her not to leave any one alone, and she scanned the paper in search of any tiny soul that could be lost or isolated somewhere, intending to provide their reconnection.

Les Ames Errantes (Wandering Souls, red), detail © Fiorenza Menini 2016

Les Ames Errantes (Wandering Souls, red), detail © Fiorenza Menini 2016Sometimes two lines appear in the drawings, denoting the edges of the Promenade des Anglais. These lost souls Menini is trying to reconnect are those of the missing persons, and Menini suffered greatly thinking of them. She had a terrible sensation that, while the comings and goings of passersby had resumed on the promenade in the months after the attack, there were still unseen souls wandering distraught and alone. This empathic feeling of distress and loneliness was unbearable, and Menini wanted none of them to feel lost. Creating these drawings eased her tension and allowed her to move past deep stress to inwardly relax and visualize the dead reunited with each other, or with the living. The drawings take an aerial view, as if from space, making the drawings appear as constellations.

Aside from these series, a few unique drawings arose. One of these is Trauma, a very simple visual of a red spot on a sheet folded in two, like a Rorschach test or a representation of two cerebral hemispheres. The word “trauma” is located here and there, multiplied like an echo repeating itself endlessly, delimiting the interior and exterior brain. Another, more complex, drawing is constructed out of over a hundred sentences rolled together, words so tiny they are no longer distinguishable. It is Menini’s observation of her own memory, having created and stored the traumatic event. The words “horror” and “fear” are repeated.

Les Ames Errantes (Wandering Souls, black), detail © Fiorenza Menini 2016

Les Ames Errantes (Wandering Souls, black), detail © Fiorenza Menini 2016Another group of large drawings denote physical parts of bodies, especially interior pieces. Like aftershocks of an earthquake, some of these drawings portray great violence and its reverberations. Some look like bones or vertebral columns and are again made with palm prints of her hands or forearms pressed onto paper. She would imagine her hands bathing in ink, and the black ink reaching up to her elbows. Other drawings of this group lose the physical, bony aspect, and look more like garlands, trees, trunks, or more abstract, lighter forms, spiritual beings moving in space.

The Mourners is the only figurative group of drawings, and they are all the same: naked women balled up on the ground, knees bent under bellies, heads buried in the arms, and long black hair, like a river that seems to at once flow away from them, and cover them as protection. Menini describes the role of deep sorrow as both an outward flow and a life-saving (self-protective) veil. Menini did not look at these drawings for a year, and even then, had a hard time doing so. She prepared a text for a public reading in tribute to the victims, during an evening on the one-year anniversary of the massacre. She had been invited to share her story and work in the city of Nice’s forum on resiliency. She did not like the drawings, but this year (2018) she suddenly published two online. Though hesitant to do so, she found it even more embarrassing to keep the drawings hidden.

In retrospect, Menini says that each drawing made the invisible visible on several levels. Having removed tubers of fear from her own body, she could then symbolically reconstruct the bodies of the victims, refitting bones, reconstructing pelvises, releasing caught energies, reconnecting lost souls. She describes this process poetically, as: “Finding the symbolic language, traversing pockets of trauma, melting crystallized memories, letting tears flow and faces disappear. I flew far into the sky, then back into the pure suffering of an exploding eye or a dividing brain. The light came back as I went through all the bodies, all the souls present, the aftershocks, and all the memories, to return once again to humanity.”** It impressed upon me how her drawings trace Menini’s journey from trauma toward healing and recollection. The shock was so intense that without the drawings, she says, she would have no memory of that night at all, from the moment the fatal truck appeared. Up until that moment, she had been taking photographs of the evening’s revelers. In retrospect, some of these pictures hold an uncanny foreboding.

Photos du 14, Promenade des Anglais © Fiorenza Menini 2016

Photos du 14, Promenade des Anglais © Fiorenza Menini 2016She states, “These photos are beyond me, they seem to have their own life, their own story.”*** They were taken just minutes before the truck's impact on the Promenade des Anglais, before she found herself facing the truck. It took her 13 months to process these photos of passersby on the promenade. She had arrived late, when the fireworks had almost finished. The photos were taken a few minutes or seconds before the attack. Like other survivors, she was unable to join the crowd on the day of the one-year commemoration in Nice. Instead, she chose to spend the day editing the photos with great care and delicacy. She was surprised by their strangeness and beauty, as she is not a photojournalist but a visual artist. We are fragile beings, humans. Drawing and meditation helped her find herself, as well as connecting with others who had similar experiences.

Enduring trauma, such as in a terrorist attack, affects the very chemistry, sinews, and spirit of one’s being. Having studied dance/movement therapy and having researched worldwide applications of embodied ways of healing trauma in-depth, I am curious, both professionally and in a deeply personal way, about how artists metabolize trauma through the creative process. As a writer, Maria Popova eloquently states of the work of performance artist Marina Abramović, who suffered chronic trauma during childhood, “Her medium is, above all, the human spirit—something she handles with meticulous care and deep respect, with staunch opposition to nihilism, and always with an eye toward the essential sense of purpose that nourishes the human experience.”**** The same could be said of my experience over four years with Fiorenza Menini, whose strong spirit and creative renewal shine through a number of tragedies she has witnessed and endured.

Photos du 14, Promenade des Anglais © Fiorenza Menini 2016

Photos du 14, Promenade des Anglais © Fiorenza Menini 2016Menini was quite generous in responding to my questions about her experiences following the attack and her willingness to share the drawings she had created in the days and weeks afterward. Healing from trauma is deeply necessary on personal, creative, community, and global levels. My deep gratitude to artists of all kinds who lead the way for us all.

Sarah C. Beasley (Sera Kunzang Lhamo), a Nyingma practitioner since 2000, is an experienced teacher, writer, editor, and artist. She has a degree in Studio Art and a Graduate Certificate in Education. Sarah spent close to seven years in retreat under the guidance of Lama Tharchin Rinpoche and Thinley Norbu Rinpoche. She offers a workshop, Meditations for Death, Dying & Living, which includes an Expressive Arts component. With a lifelong passion for wilderness, she has summited Mt. Kenya and Mt. Baker, among other peaks. Her work can be seen at Moondrop Meditation.

* Personal correspondence with Fiorenza Menini, 23 July 2018.

** Personal correspondence with Fiorenza Menini, 23 July 2018.

*** Les photos du 14 (Fiorenza Floraline Menini)

**** Some of Today’s Most Prominent Artists on Courage, Creativity, Criticism, Success, and What It Means to Be a Great Artist (Brainpickings)

References

Harris, David Alan. “Pathways to embodied empathy and reconciliation after atrocity: Former boy soldiers in a dance/movement therapy group in Sierra Leone.” Intervention 5, 3; 2007. 203–31

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Threads of Tranquillity in the Paintings of Trang T. Lê

The Wisdom of Not-Knowing: essays on Psychotherapy, Buddhism and life experience – Book Review

Spiritual Bypassing and the Dangers of Unresolved Emotional Wounds

Self, Other, and the Spaces Between: Behind the Lens with Niçoise Photographer Fiorenza Menini

Improving the Lives of People with ALS through Mindfulness