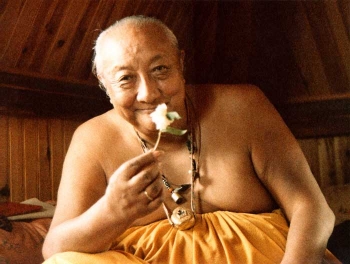

Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche (b. 1963) is the third son of Kangyur Rinpoche, and was recognized as one of the incarnations of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö—one of the greatest Tibetan masters of the last century—by HH Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, HH Dudjom Rinpoche, and HH the 16th Karmapa. Rinpoche grew up in Darjeeling in India and received teachings from many teachers, primarily his father, Dudjom Rinpoche, Trulshik Rinpoche, and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, with whom he spent a great deal of time. He is now based at the Chanteloube Centre of Studies in Dordogne, France, where he leads retreats and seminars with his two older brothers Tulku Pema Wangyal Rinpoche and Rangdröl Rinpoche. Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche also oversees the work of the Padmakara Translation Group, which has translated a number of important texts from Tibetan into Western languages. Frances McDonald interviewed Rinpoche on a recent visit to Hong Kong.

Frances McDonald: Rinpoche, you and Tulku Pema Wangyal Rinpoche have been hosting long retreats in the Dordogne for many years now, I think since 1980? Has there been an increase or decrease in interest in the three-year retreat over the years?

Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche: There’s still an increase in people wanting to do the retreat. I don’t know whether the people who are wanting to do it are totally aware of what it entails, but there’s definitely no decrease.

FM: How many people do you get, approximately?

JKR: I think there’s more than a hundred at the moment wanting to do the retreat, although there hasn’t been any kind of advertising or anything. And there’s definitely not a hundred places!

FM: How many places do you have?

JKR: I think fifty, or around that much.

FM: Do the students require some kind of background to do the retreat?

JKR: I think so, yes. Of course, it would be great if most of the students knew what they were going to be doing. Not just for retreats—I think even for wanting to study the Dharma, it’s really important that people know what it’s about. It’s very difficult for people to know even with Buddhist teachings whether it’s a religion, whether it’s a philosophy . . . similarly for retreat, I think people might have quite a lot of misunderstandings about what retreat might do. Some might think, “I’m going to go into retreat, and this is going to make me happy. This is going to take care of all my confusion and all my difficulties.” It’s not quite that! As we know, going to school or getting a job is not going to solve all our problems. It might help us see things differently. Similarly with retreat. I think it’s really helpful if people can understand what it entails. For those who do the retreat there is a questionnaire that they need to answer, as to whether they have any background in Buddhist practices or not. If they have, then, is there anyone who can advise us as to whether they are ready to do retreat or not. There are quite a lot of things that need addressing.

FM: What do you feel are the benefits of the traditional three-year retreat for Westerners?

JKR: Well, from one point of view that’s an interesting question, but from a certain point of view, it’s really not! When we say “traditional retreat,” we seem to stress the traditional aspect—it’s not necessarily a tradition. These retreats were put together so that people can practice in a manner where they are least disturbed and where they have the most information possible for doing retreat. Because that continued, it became a tradition, but I don’t think that there is a “traditional” retreat.

FM: It doesn’t follow a similar curriculum as in Tibet?

JKR: It does, but I mean, as to what a tradition is, that’s really quite interesting. Most of these traditions weren’t started off as a tradition. It’s really like the tradition of teaching the alphabet— because it was handed down from one to another, it became a tradition. As to the real benefit of traditional retreat—it’s almost the same as saying, “What is the benefit of practicing, as a Buddhist”? Well, the benefit of practicing, or of meditating, obviously is in order that we can start studying the process of becoming a Buddha. And the process of becoming a Buddha, depending on different individuals, has different requirements. For example, somebody who is very good at balancing will require less training in walking a tightrope than somebody who doesn’t at all have any balance, even in their daily life. Retreat is a way we can train ourselves to develop such a balance. So from that point of view, “What’s the benefit of doing a traditional retreat,”? it’s more like, “What’s the benefit of practicing? What’s the benefit of following the Buddha’s teachings”? For a Buddhist, the benefit should be that it takes us a little bit closer to understanding what becoming awakened is about.

FM: You also run “parallel retreats,” in which students do the same practices but over a longer period of time, while still staying at home and doing a job. Could you say something about those?

JKR: They’ve been set up mainly for people who would like to follow the stricter three-year retreats but who don’t have the means, whether through time or responsibilities. It’s mainly trying to follow that but without being closed off in a retreat situation.

FM: Do you feel the benefits are the same?

JKR: The outcome should be the same. As to whether the benefits are the same, it’s difficult to say because it really depends on each individual, how much time they’re able to give to it.

FM: There can be a lot of problems readjusting after a closed three-year retreat.

JKR: Of course. There’s trouble readjusting with everything, not just retreat! Many people who are married for very many years also have trouble readjusting. These days especially, when a lot of people lose jobs, they have trouble readjusting to