Meir Shahar’s Oedipal God: The Chinese Nezha and His Indian Origins is a tour de force that has raised the bar for gripping writing and scholarly daring in Buddhist Studies. The god of this study, Nezha, is a beloved but relatively inconsequential divinity in Chinese Buddhism. Often seen in Chinese folk temples as an attendant to Guanyin, he cannot match her importance or that of other prime bodhisattvas in the Buddhist pantheon. Yet through him, Shahar has masterfully brought together two towering schools of thought, Buddhism and Freudian psychology, in one valuable book. He also reminds us of Nezha’s tantric origins and how he was part of an entire spiritual tradition that diffused into Tang dynasty (618–907) China.

Professor Meir Shahar. From wikipedia.org

Professor Meir Shahar. From wikipedia.orgThe 17th century Chinese text The Canonization of the Gods sets the scene for Nezha’s portrayal in Chinese culture as a defiant, unfilial boy. According to the story, which is set in the Zhou era (1046–771 BCE), his father, the general Li Jing, cut him out from a ball of flesh that emerged from his mother Lady Yin after a three-year pregnancy. At the age of seven, following a dispute, Nezha killed the heir of the dragon king, before engaging in a vicious fight with Li Jing, who hated his son for bringing the dragon king’s wrath on the Li family. Nezha offered to commit suicide, and declared that he would “return” his sinful body to his parents. The dragon king’s coterie and his father assented, the latter notably indifferent to Nezha’s death as opposed to the stricken Lady Yin.

The second half of the Nezha story brings the father-son conflict into the foreground much more brazenly than does Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, the Greek tragedy that provided the name for Sigmund Freud’s theory of the Oedipus complex (the desire of the young son for his mother and the fantasy of deposing his father in order to be the sole recipient of her affections). The dead boy’s wandering spirit sought help from his teacher, the Daoist immortal Taiyi, who advised that he could be resurrected through incense offerings in a temple of his own.

Nezha therefore appeared to his grieving mother in a dream, demanding that she build him a temple. Lady Yin did so, but fearing her husband’s wrath (as he was glad their son was dead), decided not to inform him. However, Li Jing did find out, and after chasing out all the temple pilgrims, burned it down in a rage. Furious, Nezha incarnated on earth in an indestructible body and engaged in a titanic struggle with Li Jing until they were forced into an uneasy truce. This violent and frankly unpleasant story, particularly to Chinese sensibilities, still has not prevented Nezha from becoming a popular deity in a Confucian society.

As Shahar’s introduction points out, the book does two things: it explores the applicability of Freudian theories to Chinese culture, and analyzes the impact of esoteric Buddhism on the Chinese conception of divinity. Particular credit has to be given to the translator and imperial monk Amoghavajra (704–74), who brought a relatively obscure tantric deity into the popular sphere of Chinese worship through translating the tantric manual Rituals of Vaishravana, a text attributed to his authorship. But this tantric genealogy is not revealed until Chapter 8. Chapter 1 first analyzes the widespread trope of the father-son conflict in world and Chinese literature. Chapter 2 then examines the tension between the father-son conflict and the universal demand of Chinese culture: filial piety, or deference to elders, and especially to the patriarch.

In Chapter 3, the author dives into a Freudian analysis of Nezha’s story, which has the additional function of identifying Freudian themes in Chinese literature and society. Shahar pays tribute to Chinese scholars who have already identified Nezha as the Chinese counterpart to Oedipus Rex. The mother is the first woman a male knows and attaches to, but his father is an unsurpassable rival: not just physically or economically (the young boy is dependent on the father’s breadwinning), but by fact of the father-mother union on which the son’s very existence depends. The son’s fantasy is therefore hopeless, and he must sublimate it both for his own good and for that of society. It is the first lesson in limitations that the child learns, the very first “coming to terms” he must experience in order to be a socially and sexually adjusted man (pp. 38–40). Where there is a family, there is necessarily the Oedipus complex (or the Elektra complex for females, the primal desire for the father that also needs to be channeled).

There are few cultures that exalt the trope of the mother-son bond both in literature and real life like Chinese culture does, and Shahar provides a balanced hypothesis of why this might be so, attributing the primacy of the mother-son bond to Confucian social mores and the codependence of a woman and her son under post-Song (960–1279) patriarchy (pp. 56–8). Some psychologists believe that the Chinese experience of the Oedipus complex was slightly “superior” to that of the West: “. . . because the oedipal attachment to the mother was allowed to be vented, it rarely led to a confrontation between son and father (the latter accepting his spouse’s bond with his offspring)” (p. 57). This is quite different to the Western, non-Confucian experience where, as we see in Oedipus Rex, King Lear, and many other masterpieces, the son always ends up killing the father, only to suffer divine repercussions or tragedy in return.

Chapter 4 discusses Nezha’s various appearances in Asian pop culture, ranging from a Communist liberator and revolutionary to an edgy, maladjusted teen in a Taiwanese soap, or even a protagonist in post-1990s Japanese manga and anime. Chapter 5 examines the most famous aspect of the deity, his martial prowess, and the background to his myriad superpowers. Chapter 6 goes on to explain how Nezha’s second-most famous motif, his appearance as a Peter Pan-like perpetual boy, came to be. The shadow of the father again moves to the forefront in Chapter 7, which focuses on our protagonist in the Daoist interpretation.

Nezha’s Buddhist heritage is fully revealed in Chapter 8. Shahar explains how he originally served as messenger to his father, the Buddhist deity Vaishravana, who is associated with wealth and war (p. 153). Tantric masters like Amoghavajra and Vajrabodhi (671–741) believed that Vaishravana’s children were also his messengers, and that they could be invoked through mantras and mandalas (pp. 158–60). These junior deities blessed Vaishravana’s followers with wealth, but they also commanded his armies, which in 742 Amoghavajra famously invoked to repel Emperor Xuanzong’s (r. 712–56) enemies in Rituals of Vaishravana. It was Amoghavajra who transcribed the name of one of these children-generals, Nalakubara, into the Chinese equivalent Nazhajuwaluo, which then became Nazha (seven centuries later, the mouth radical would be added to the first character in the name, resulting in the slight change to Nezha). In Chapter 9, Nalakubara’s Indian origins are traced back to the Krishna myth, outlining antecedents that would eventually provide the backdrop for the Chinese story to emerge.

Shahar’s book is challenging in the best sense of the word. It traces Nezha’s esoteric ties to tantric Buddhism, and brings to the forefront the many influences that cultural forces have had on the god: most notably, Hindu antecedents, the Oedipus complex, and tensions of filial piety in Chinese literature and society. This is a fine example of Buddhist Studies and an engaging introduction to the interdisciplinary approach.

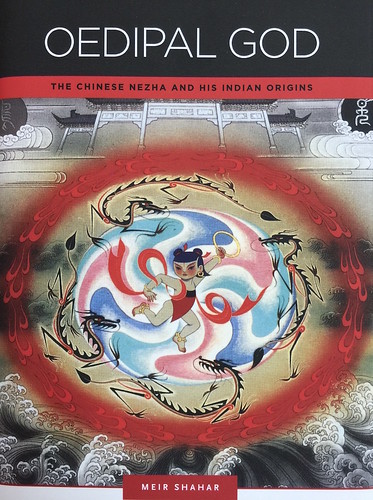

Oedipal God: The Chinese Nezha and His Indian Origins, by Meir Shahar, was published by University of Hawai‘i Press, Honolulu, in 2015.