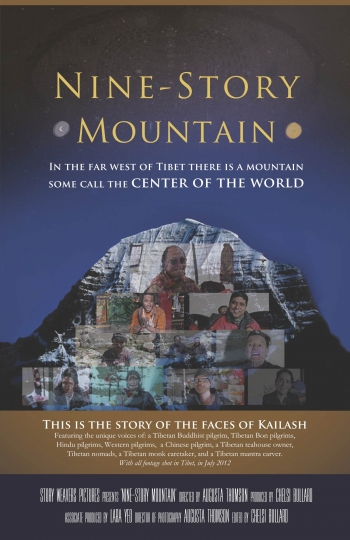

Good filmmaking provides immersion in illusion. When we sit down for what is usually more than an hour to stare at a screen, we need the film to convince and effectively trick us into believing we are doing more than that. We need to be captivated by the movie’s journey. Whichever techniques and philosophy the filmmaker decides to pursue, the illusion offered by their movie needs to be meaningful and affective. It is for this reason that well-made documentaries about real lives, people, and stories are even more valuable than excellent fictional movies. Documentaries like Augusta Thomson’s Nine-Story Mountain are doubly appreciated because they not only immerse you in a fantastic world (in this case, the world of Mount Kailash and its Buddhist-Hindu-Bön cultures), but a world that truly exists and invites real-life engagement.

FEATURES|THEMES|Art and Archaeology

Stories of the Holiest Summit on Earth

Buddhistdoor Global | 2014-03-13 |

Dark blue and quicksilver shades of Lake Manasarovar. Screenshot from the film.

Dark blue and quicksilver shades of Lake Manasarovar. Screenshot from the film. Upen, a Hindu pilgrim. Screenshot from the film.

Upen, a Hindu pilgrim. Screenshot from the film. Atsi and Tharpa share their ideas about Mount Kailash with the crew. Screenshot from the film.

Atsi and Tharpa share their ideas about Mount Kailash with the crew. Screenshot from the film. Lara Yeo with a fellow pilgrim. Screenshot from the film.

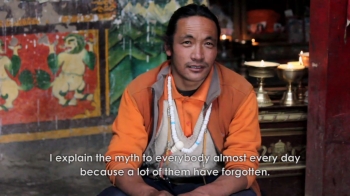

Lara Yeo with a fellow pilgrim. Screenshot from the film. Migyur Dorje gives story-maps to visitors to his temple to preserve the myths. Screenshot from the film.

Migyur Dorje gives story-maps to visitors to his temple to preserve the myths. Screenshot from the film. Don Nelson reflects on the meaning of pilgrimage and Mount Kailash. Screenshot from the film.

Don Nelson reflects on the meaning of pilgrimage and Mount Kailash. Screenshot from the film. Nine-Story Mountain premiered on March 7, 2014.

Nine-Story Mountain premiered on March 7, 2014.Although the immersion is undeniably present in Thomson’s film (and it is of the gentle, gradual kind), she is not presenting an illusion like other film directors. Mount Kailash is no fiction, its stories are still being inherited, and the film successfully summons the viewer to join the core crew of Thomson, graduate student Lara Yeo, and photographer Don Nelson on the kailash kora. The journey of the movie has suddenly become something greater. It is now a pilgrimage. As Thomson has noted, this is not a film about pilgrimage but a pilgrimage through film.

The structure of Nine-Story Mountain is straightforward. It combines footage taken by Nelson, the entourage’s photographer, with film footage of scenic landmarks and interviews with an array of different travelers. The communal and individual tales are told in a linear manner, beginning at Lhasa and concluding at Nyalam County (both in Tibet). The material is woven together with a basic but effective combination of prudently timed text, an on-screen “faded journal” effect to remind the audience of different milestones, and creative animations that bring the wider story and some of the local myths to life.

The panoramic visuals are from Nelson’s still photography and his masterful use of different angles, from wide-panning shots of Mount Kailash or Topchen Valley to medium-distance footage of Trangmar Gorge and Lake Manasarovar. Thomson’s own filming of nomad tents, tourist campsites, or stone mantra carvers with an HD camera is quite sufficient given the fine visual results. The selected music (both produced in-house and sourced from various artists) is atmospheric and respectful, and the film is embroidered with many legends and fables that are beautifully illustrated and animated. The main strength of the film is that it is not dependent on the equipment budget or even the planning that led to its production (it was upon visiting Lake Manasarovar that Thomson felt that the pilgrimage could gradually evolve into a movie).

At the heart of the film’s special ambience is Thomson and Yeo’s unforced but eloquent storytelling. The narration and interviews are presented professionally and naturally. Thomson is able to inform and challenge her audiences with an engaging account that does not distract from the camera’s subjects and scenery. She also opens up plenty of questions for the viewers to reflect on. The interaction the crew enjoys with different pilgrims is particularly welcome because they unite the natural majesty of Mount Kailash and its trekking route with the intimacy of smiling Hindu gurus, Tibetan Bön and Buddhist locals, Chinese pilgrims, and many more human faces. Difficult times and complicated questions are not glossed over or ignored. Indeed, the story is all the more poignant when we are able to learn of Gauresh and Samut’s struggle with the high altitude and rough terrain or Yeo’s occasional exhaustion. Papar Tashi’s concern about pilgrims’ environmental footprints, or Migyur Dorje’s story-maps for travelers and locals unaware of Mount Kailash’s legends, are critical aides-mémoires that the peak has an ecological and mythic life of its own, with real people devoted to preserving it.

The core crew had to work hard at multitasking. Excluding external input and outsourced material, the full film staff numbers no more than ten, among it a translator, an illustrator, and a composer. This film is an immense credit to the team’s impressive post-production coordination. It is a labor of love, supported by many who shared the core team’s depth of sophistication and sense of hard work. In the

context of a documentary aimed at raising awareness of Mount Kailash, love for the work is what distinguishes a documentary like this from others. Its vision is not only to spread knowledge, which many other non-fiction films do as well. It articulates the significance of pilgrimage for locals as well as a Western trio. Here, journalism and filmmaking develop into an act of cultural preservation.

Circumambulation always brings us full circle. Pilgrimage and blessings radiate outward from Mount Kailash for Hindus, Buddhists, and Bön devotees alike. In a similar way that the unclimbable status of Mount Kailash lends it an even more profound dignity, the film can only ever be a glimpse of the simultaneous splendor and intimacy a pilgrimage offers. Nevertheless, it is a superb film experience, and one that notably doesn’t rely on illusion. There is also a clear but very gentle moral to the entire tale. It outlines the ethical duty by pilgrims and journalists to tell the mountain’s story, which has riches that cannot be exhausted.

See more about the film on Buddhistdoor

Categories:

Comments:

Share your thoughts: