Tam Po Shek. From Buddhistdoor Global

Tam Po Shek. From Buddhistdoor Global From Buddhistdoor Global

From Buddhistdoor GlobalLooking as serene in person as he does on stage, Tam Po Shek welcomed us to his Chinese interior-style apartment garbed in an exquisite tangzhuang (唐裝). The traditional furniture and aesthetics of his home form a statement to his lifelong passion for Hong Kong’s artistic scene. He showed our photographer, Paul, and I the flutes (dong xiao 洞簫) that he lovingly chipped out of bamboo, crafted, and painted. They were exquisite. Already beautiful unadorned (we caught a glimpse of the uncompleted ones), it was difficult to imagine how much more time he would have spent painting the sutras and bodhisattva images on them. It was clear how he earned the informal epithet, “Master of the Flute” (dong xiao da shi 洞簫大師).

Listeners of the Chinese instrument virtuoso may already understand why Tibetan singer Dechen Shak-Dagsay invited him to collaborate on her Chinese edition of Jewel. But it was only by observing him, along with his leisurely pace and hearty mirth, that I understood how he makes each day a work of art, and how his spirituality informs everything he creates.

The Gate of Clouds on a Rainy Night

Mr. Tam was first introduced to Tibetan Buddhism in 1986 – 87. But as the years passed, he studied under the Tien Tai tradition, which he found very satisfying, before settling into Pure Land – the “simplest” of them all. His sense of genuine simplicity had already influenced his art: as the Buddha said, he recalls, the mind creates the world. “Simplicity, jian dan (簡單), is my favorite way of doing and being,” he emphasizes with a twinkle in his eye, repeating his watchword several times throughout our conversation.

Buddhism changed his outlook and the relationship he shared with the world. His fondness for simplicity also grew as his preferences evolved into a minimalistic flair. His musical style

is reminiscent of the Daoist idea of “complexity amidst spontaneity”. Mr. Tam invokes Chinese philosophy to explain his minimalism. “Spirit (ling 零) is what truly draws out affective power (qing gan 情感) in the interaction between artist and viewer, performer and audience. Spirit and music must sing in unity: only then does it purify and beautify,” he says.

One night he heard a mighty storm, and listened to the myriad raindrops tinkling on the roof and hitting the floor amidst the rumble of thunder. This ambience was the sole inspiration for his piece The Gate of Clouds on a Rainy Night (yun men ye yu 雲門夜雨), a flute solo that embodies his present artistic philosophy.

Purpose, Preservation, Passion

Mr. Tam believes in the virtues of traditional culture. He speaks unapologetically about the harm modernism, in its most basic sense, has done to the preservation and progress of Chinese art. As the sun set on Imperial China, reformists believed that the old was to be discarded, and what was new had to be better than what came before – from technology to the arts to culture. To be sure, progress always comes at some expense of the past. But Mr. Tam is concerned this has led to a persistent problem for today’s youth. “By sacrificing preservation at the altar of progress, we have lost the passion that once inspired young people to seek a career in the artistic or cultural professions,” he says. Religion, arts and humanities, along with other things that teach us to tell and critique the human story, were condemned or co-opted by a technocratic society. “The artist’s task is to help their patrons and the public feel a kind of ‘enlightened self-interest’ to participate in art,” he urges. If successful, perhaps the ancient ways can coexist with and even benefit our modernist, technological world.

“It’s difficult to get someone interested in something that they don’t see any use in,” he concedes. “People will throw away things they feel are purposeless. We need to help them rediscover the purpose and fulfillment found in learning traditional Chinese instruments.” He argues his calligraphy class is growing each year because students learn so much about their bodies and habits through practicing their brushstrokes. When they are able to learn so much about themselves and the Chinese heritage, the purpose of calligraphy speaks for itself.

Bearing Witness

On his table is a gift from a friend: a beautiful Rolleiflex T. He has many more camera models, some expressly for only black and white images. Photography matches the same high standards he has for his calligraphy, music, and painting, because it is just one more art form: another means to “capture” the world. For Mr. Tam, it is not the pose or angle or lighting that matters, but the moments of great emotion and life. Particularly dear to him is the work of war photographers, who take immense risks to bear witness to the ultimate drama of life, death.

Mr. Tam carries a flute or guqin (古琴) rather than a rifle, but he also doesn’t follow the conventional rules of photography. “If I have a break when performing,” he laughs, “I take my camera with me for a wander and I just take whatever photos that inspire me.” Yet spontaneous photography is not a matter of pure fun. It can be serious, and serious photography is usually not of the smartphone selfie sort. Good photography presents, without judgment, snapshots of emotional power and significance.

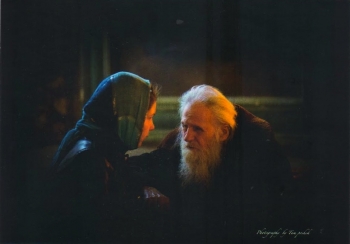

Elder in a Russian Orthodox Church. Photography by Tam Po Shek

Elder in a Russian Orthodox Church. Photography by Tam Po ShekThe common theme of this diverse artist’s work is nurture. Just as Buddhism nourished his spiritual life, he was blessed with the chance to develop the Chinese cultural beat with his talent and hard work. Perhaps the most fitting imagery for his cultivation is a photo he took of an elderly man inside a church in Russia. It is one of the darkest man-made interiors in the world, so one has to be particularly skilled and lucky to shoot anything. The elder looks as if he were huddled in a pillar of light.

Visit Tam Po Shek’s Flickr Photostream here.