FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

Tara: A Powerful Feminine Force in the Buddhist Pantheon

Tara, Sino-Tibetan, probably 18th century, gilt bronze

with red coral inlay, 6-7/8 x 5-3/8 x 5-7/16 inches.

Collection of Scripps College, Claremont, California

In the northern schools of Buddhism, the rich traditional pantheon of deities is, like in many religious and spiritual traditions, somewhat male-dominated. At the center is Shakyamuni Buddha, a man who lived among us some 2,500 years ago and attained spiritual perfection.

In the Tantric traditions of the Himalayas, there are also the Five Dhyani-Buddhas or Five Tathagatas (self-born, celestial)—Vairocana, Amoghasiddhi, Amitabha, Ratnasambhava, and Akshobhya—all manifestations of various teachings and spiritual powers of the Buddha, and also all male. Bodhisattvas, compassionate beings who have postponed their own enlightenment to remain in this realm and help other sentien beings, are also described in texts and depicted in art as male, although the most revered of these, Avalokiteshvara sometimes assumes female form.

Then there are arhats (holy men), Kings of Light, wrathful deities, and various lesser divinities who help followers along their spiritual path. These too are mostly male and are often depicted embracing their female consorts. Independent female deities are relatively scarce, however there is one Buddhist deity who is not only supremely beautiful in her representations, but is also believed to possess spiritual power that is at least the equal of her male cosmic counterparts: Tara.

Tara is undoubtedly the most powerful female deity in the Buddhist pantheon. Her name means “star” in Sanskrit and she is believed to possess the ability to guide followers, like a star, on their spiritual path. In some northern Buddhist traditions, she is considered a bodhisattva and is often described in texts and depicted in imagery as the female consort of the most widely revered bodhisattva, Avalokiteshvara. In some Buddhist legends, it is said that she was born from one of Avalokiteshvara’s tears, shed in a moment of deep compassion. Other Buddhist legends, however, tell of a devout Buddhist princess who lived millions of years ago who became a bodhisattva, vowing to keep being reborn in female form (rather than in male form, which was considered more advanced on the path to enlightenment) to continue helping others. She remained in a state of meditation for 10 million years, thus releasing tens of millions of beings from suffering. Since then, she has manifested her enlightenment as the goddess Tara.

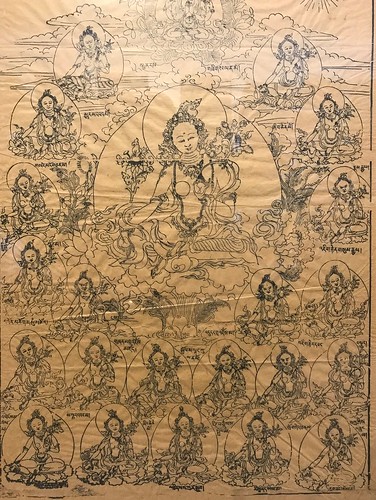

Green Tara and the 21 Taras, Tibetan, 19th century,

woodblock printed ink on paper. Collection of Scripps College

In the Himalayan region, especially in Tibet and Nepal, Tara’s status is more that of a supreme goddess or female buddha than a bodhisattva. She is referred to as the Wisdom Goddess, the Embodiment of Perfected Wisdom, the Goddess of Universal Compassion, and the Mother of all Buddhas. As benefits such a supremely powerful and compassionate deity, she is often depicted in painting and sculpture seated on a lotus throne in a pose that is at once regal and solicitous. The “pose of royal ease,” or lalitasana, is typically adopted by bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Maitreya, usually depicted sitting in lotus position with the right leg hanging down over the edge of the lotus, or bent with the knee up and foot flat on the ground. In Tara’s case, however, her right foot is usually shown positioned on a smaller lotus, not so much relaxing but apparently poised to propel her into action should her followers need her assistance.

Green Tara by Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, 2008. Pieced-silk thangka,

silk, satin, and brocade, gold and pearl, 53 x 35 inches.

Image courtesy of the artist

In Himalayan representations, Tara can appear in as many as 21 forms, and in painting and pieced-silk images, she is depicted in five different colors—like the Five Dhyani-Buddhas—the most common of which are Green Tara (after a Chinese princess in a Buddhist legend) and White Tara (after a Nepalese princess). Green Tara is associated with enlightened activity and active compassion, and is the manifestation from which all her other forms emanate. In the pieced-silk thangka by artist Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, Green Tara is shown seated on her lotus throne holding lotuses, an attribute that she shares with her male counterpart, Avalokiteshvara. Her lotus is usually the blue or night lotus (Skt: utpala), a flower that releases its fragrance with the appearance of the moon. So as well as being associated with the stars, Tara is also related to the moon and the night. As Green Tara, she is also associated with fertility and the growth and nourishment of plants, flowers, and trees.

White Tara by Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo, 2001.

Pieced-silk thangka, silk, satin, and brocade,

58 x 30 inches including brocade frame.

Image courtesy of the artist

White Tara is associated with maternal compassion and healing. In many representations, she has eyes in the palms of her hands and on the soles of her feet, as well as in the center of her forehead, representing her power to see those who are suffering and offer her aid. The pieced-silk thangka illustrated above clearly depicts the eyes in her palms, as she holds her right palm outward to grant the wishes of her followers. White Tara is specifically associated with practices aimed at lengthening one’s lifespan in order to continue the practice of the Dharma and to progress further along the path to spiritual fulfillment.

Tara, Sino-Tibetan 18th–19th century, gilt bronze,

20 x 13-1/2 x 9-1/2 inches. Collection of Scripps College

With all of these attributes, Tara has much to offer female Buddhists. For much of the history of Buddhism, female practitioners have been taught than in order to attain enlightenment they must be reborn as a male; only then can they progress toward full spiritual liberation. The presence of Tara in the Buddhist pantheon over the centuries, both as a bodhisattva and as a female buddha, has offered a sense of inclusivity and hope of spiritual salvation to many female practitioners. Sculptures such as this elegant 18th or 19th century bronze figure from Nepal, which manifests the serenity that comes with the perfected wisdom and the grace that accompanies true compassion, are some of the world’s most exquisite and potent representations of female spirituality.

More Buddhist images by Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo can be found at www.threadsofawakening.com

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Blessings of White Tara Beyond Time and Space

STEM Tara: Bringing Science Education to Buddhist Nuns

The Dakini at the Bus Stop

The Contemporary Newar Art Movement of the Kathmandu Valley

The Making of Buddhist Wood Sculptures in China