FEATURES|VEHICLES|Mahayana

The Cypress in the Courtyard: An Interview with Venerable Ming Hai

A monk asked Master Zhao Zhou, “Why did Bodhidharma come from the west?”

Master Zhao Zhou replied, “The Cypress in the Courtyard.”

The Gateless Gate (無門關), Master Wu Men Hui Kai (無門慧開)

As vice-president of the Buddhist Association of China and abbot of Bai Lin Temple (柏林禪寺), Venerable Ming Hai (明海) understands perfectly that much needs to be done in terms of propagating the Dharma, especially while Buddhism is undergoing something of a renaissance in China and the general public is showing an unprecedented level of interest in Chan Buddhism.

Holding a degree in philosophy from Peking University, Ven. Ming Hai was ordained as a Chan monk at a young age in 1993, under the supervision of Ven. Jing Hui (淨慧). He has served as the abbot of Bai Lin Temple, in the southeast of Zhao Xian County, in China’s Hebei Province, since 2004. Built in 3rd century, the temple was given the name “Bai Lin,” meaning Cypress Woods, during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) because of the numerous Cypress trees growing nearby at that time. When Ven. attended an academic conference in Hong Kong a few months ago, Buddhistdoor Global had an opportunity to talk with him about Bai Lin Temple and recent developments for Chan Buddhism in mainland China.

“From the late Qing dynasty [1636–1912], Buddhism began to decline in China. It was a collective karma and Bai Lin Temple was inevitably a part of that. As a man sows, so shall he reap; we simply have to accept it.” Ven. Ming Hai explained. “Before that, the temple had trained generations of eminent Chan masters, including Master Zhao Zhou Cong Shen [趙州從諗禪師, 778–897] and Master Yue Xi [月溪禪師, 1130–1200].”

Indeed, Bai Lin Temple has borne witness to the ever-changing religious circumstances in China that ultimately lead to Buddhism’s decline. The temple flourished until the 1940s, when China experienced a series of social and political upheavals, culminating in the devastating Cultural Revolution. Bai Lin Temple eventually became completely dilapidated, and only the stupa of Master Zhao Zhou remained standing.

It was not until 1988, when Ven. Jing Hui was appointed abbot, that there came any hope of renovation. He was astonished to find that only three other venerables remained in residence, and that this once sacred temple was little more than ruins.

“Ven. Jing Hui vowed to renovate the temple and to reinvigorate Chan Buddhism so that Bai Lin Temple could once again become a vital center of Chan,” Ven. Ming Hai recounted. Ven. Jing Hui spared no effort in organizing the renovation of Bai Lin Temple, working diligently to raise funds and urging people across Hebei to show support. By the early 1990s, basic structures such as the main gate, a Guan Yin hall, and a meditation hall were constructed. “Master Jing Hui devoted his life to Bai Lin Temple; we shall not forget his contribution,” Ven. Ming Hai emphasized.

Almost two decades have passed since then, and Bai Lin Temple is now renowned in the Chinese Buddhist community for its emphasis on teaching Chan Practice in Daily Life (生活禪). Ven. Ming Hai explained how the concept began to take shape when Ven. Jing Hui observed that most Chinese Buddhists held the misunderstanding that the study of Chan was only for the very wise. Fearing there would be a divergence detrimental to the propagation of Chan Buddhism, Ven. Jing Hui came up with a campaign to promote the practice of Chan in everyday life, aiming to reconnect the doctrinal and secular aspects of the Chan teachings.

“It is essential that we learn how to skillfully integrate the practice of Chan into the context of daily life,” Ven. Ming Hai observed. “There are so many difficulties we confront every day, ranging from workplace stress and financial problems, to health crises. All of these can actually be eased with the special Chan teachings devised by Master Jing Hui.”

Following the success of the central government’s economic reforms and the implementation of more liberal religious policies, demand for Dharma teachings among the general public grew as people began to recognize that the new abundance of material comfort was no substitute for spiritual welfare. More and more, said Ven. Ming Hai, we see members of the younger generation eschewing technological advances and embracing mindfulness meditation.

But what exactly is meditation? How should one define it? “Meditation is everywhere. It is so common and ubiquitous that it is almost overwhelming. Millions of people call themselves meditators simply because they have taken a course here and there. It is in some ways worrying, but understandable, Ven. Ming Hai noted. “Let’s take an influenza epidemic as an example: whenever a new drug hits the market and its manufacturer promises that it’s some kind of holy grail cure, people will rush to the drugstore. This is exactly the situation we are facing now. People are suffering all sorts of sicknesses, physical and mental, and meditation is the cure. And who doesn’t want to be cured?”

Ven. Ming Hai explained that in China, people sometimes refer to this phenomenon as a “blowout” (井噴), a term is originally used to describe the uncontrolled release of crude from an oil well. “Chinese traditions were undermined by the Cultural Revolution. Then came the revitalization of Buddhism in recent years, attributed to the efforts of numerous Buddhist organizations, temples, monks, nuns, and lay people,” he related. “This sudden resurgence attracted a significant number of people, with no regard for their qualifications. Some of them are only motivated by the prospect of money and reward, with a foolish plan to deceive the innocent and gullible. Meditation and Chan Buddhism are not merchandise to be sold door to door, nor skills to be mastered, and definitely not merely techniques for harnessing the mind. They represent a path toward enlightenment and something to which we should devote our lives.”

To make matters worse, Ven. Ming Hai noted, some students treat Chan merely as a manual of solutions for our daily problems. He cautioned that this unfortunate situation is widespread, especially in these troubled times when people are desperate to escape their frantic lives for a little of peace of mind. It may be intolerable, he counseled, but we must be patient; teaching the Dharma is never an easy or straightforward task.

Ven. Ming Hai, a student of Ven. Jing Hui even before he took refuge and was ordained by the master, expressed his gratitude at being able to stay close to his teacher, learning how to become a true bodhisattva. “The master himself is indeed a bodhisattva. He has always acted with a calm and peaceful mind, exerting himself solely for the benefit of the Three Jewels, rather than secular trivialities. We can learn a great deal from these masters of the older generations. The spirit of the bodhisattva is not only central to the Mahayana Buddhist tradition; it is a pillar of Chinese Buddhism. In 2,000 years of Buddhism, China has experienced four large-scale anti-Buddhist persecutions,* yet it continues to thrive and most of the time has flourished as a state religion. Why? Because the Dharma has been with the people for a long time and Buddhism has had a major influence on our spiritual lives—it is almost inseparable from the ordinary experiences of our lives.”

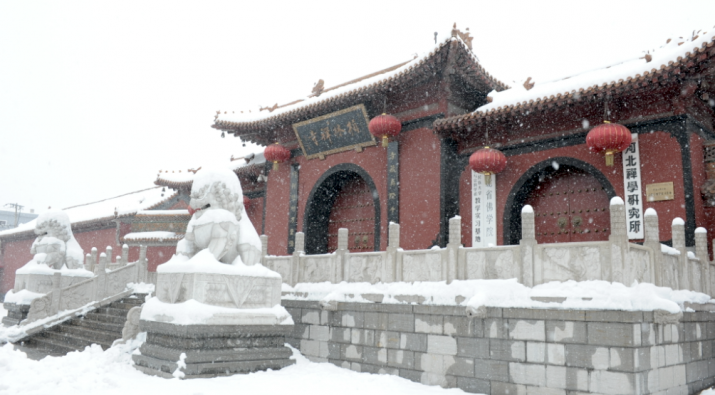

Bai Lin Temple. Image courtesy of Bai Lin Temple

Bai Lin Temple. Image courtesy of Bai Lin TempleVen. Ming Hai humbly refers himself as a bridge, with all his works built upon the foundation laid by Ven. Jing Hui, whose work, in turn, is built on the foundation of his teacher, Master Xu Yun (虛雲), all the way to the beginning of the Cao Dong school (曹洞宗).** This lineage, Ven. Ming Hai observed, is always there for anyone to pick up, and he is more than willing to offer assistance to those who want to cross the river of life and death—especially young people, which is why Bai Lin Temple has organized a summer camp for youths each year since 1993. “It’s designed specifically for the younger generation, so that they can appreciate the Dharma and emulate the life of a Chan Buddhist,” said Ven. Ming Hai. “Many have been inspired by the event and figures show that a higher proportion of participants are university students.” Various kinds of summer camps have since sprung up across China, hosting tens of thousands of students.***

“A number of decades ago, scientists were claiming that they had discovered the truth about our world. To them, the demise of religion was inevitable. Of course, there are big questions that science will never be able to answer, and this is when people turn to religions and spiritual studies,” Ven. Ming Hai related.

According to a 2012 report by the Washington, DC-based Pew Research Center on The Global Religious Landscape, 5.8 billion people expressed a religious affiliation, representing a remarkable 84 per cent of the global population as of 2010. “The world is now facing a widespread stress epidemic that appears to be running out of control. As long as we continue to indulge in this very materialistic culture and lifestyle, there will be no end to suffering,” said Ven. Ming Hai.

Many people in China believe in a strange mix of materialistic socialism; Ven. Ming Hai even jokingly labeled them as devoted disciples of Materialism with a capital M—in his words, “a quasi-religious belief.” Yet, Buddhism is in no way antagonistic to materialism. The Dharma is always about the “Middle Way”—a middle ground between the binary polarity of attachment and detachment (or non-attachment); one doesn’t necessary need to immediately abandon all worldly possessions and sink into poverty in order to practice Chan Buddhism. As Ven. reiterated, one must maintain a right attitude toward wealth to ensure it is obtained rightfully and in a balanced way.

“The sublimation of spiritualism is wisdom, and the sublimation of materialism is merit. The accumulation of merit and wisdom (福慧雙修) is a fundamental concept in Buddhism,” he concluded.

* Four anti-Buddhist persecutions were carried out from the 5th–10th centuries. The first two were initiated by Northern Zhou Emperor Wu Di (周武帝) in 574 and 577. The third was ordered by the Taoist Tang Emperor Wu Zong (唐武宗) in 845. The final one was attributed to the order of Later Zhou Emperor Shi Zong (周世宗) in 955.

** Caodong is one of the five schools of Chan Buddhism. It was founded in the Tang dynasty and is well known for its silent illumination (默照禪) techniques. According to the lineage, Master Xu Yun was the 47th patriarch, making Ven. Jing Hui the 48th and Ven. Ming Hai the 49th.

*** Synergy or Collision: University students encountering Buddhism in China (Bill M. Mak)

This article is part of “Buddhism in the People’s Republic,” a special project focusing on the schools of Mahayana Buddhism in contemporary China. Through this project, Buddhistdoor Global’s editorial team and expert contributors aim to provide a concise, insightful, and informative overview of the history of contemporary Chinese Buddhism, and the modern practices and influences that are shaping the changing face of modern China.