Original Author: Osamu Tezuka

Director: Kozo Morishita

Studio: Toei Animation

Distributed by: Warner Bros. Pictures and Toei Animation

Release date: 28/05/2011

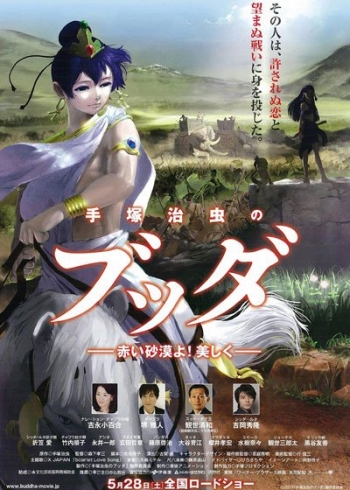

As far as I know, there have been no animated films to begin with that enjoy the same financial backing and sheer effort as Osamu Tezuka’s “Buddha”, which will be presented in three instalments. “The Great Departure” is the first movie in this manga-to-silver screen trilogy, which I watched in Amsterdam on the first night of the sixth Buddhist Film Festival Europe (1 – 3 October 2011). It is a visually sumptuous and artistically awe-inspiring film, with intriguing reinterpretations and some regrettable omissions that differ from both its manga original and the canonical accounts of the Buddha’s early life. It offers sprawling, scenic panoramas of northern India and the Himalayas, and a gritty and gory panorama of war, violent deaths and eviscerated corpses. It utilizes the latest in animation to show off the miracles of young Siddhartha, from the opening where the bodhisattva hare throws its own body into the fire to the white, six-tusked elephant that enters the stunningly drawn Queen M?y?.

Featuring an all-star voice actor cast, including Nana Mizuki as Siddhartha’s lover and the twenty-sixth Grandmaster of the Kanze School of Noh and Kyogen as the Buddha’s father, “The Great Departure” falls short in certain areas, but remains an incredible animated epic that will further propel the ineffable figure of the Buddha into Western and Japanese pop culture. Easily my favourite animated film so far, I very much look forward to welcoming the next two movies of the trilogy.

The title of the movie should render my need to provide a synopsis moot, but the title omits the several central characters, many of who are Tezuka’s original creations and not present in the Buddhist s?tras. They are: the slave Chapra and his mother, child telepath Tata, bloodthirsty warrior Bandhaka, ill-fated ascetic Naradatta, and Siddhartha’s low-caste lover, Migaila. These characters help to shape a movie that addresses not only the Buddha’s early life, but also the intersectional injustices of the caste system that wreak injustice upon the sudras while condemning those of the k?atriya (warrior or aristocratic) class to institutional oppression. The main message of the movie is that everyone – be they Prince, pauper, warrior, or commoner – loses in the caste system.

?uddhodhana, King of the ??kyas

Ruling from his throne in Kapilavastu, ?uddhodhana is the king of the ??kya clan and the ruler who needs to defend his realm from the encroaching kingdom of Kosala, whose leaders are hungry for Kapilavastu’s abundant natural resources. Despite being voiced by Kiyokazu Kanze, the current Grandmaster of the Kanze School of Noh and Kyogen, ?uddhodhana’s character is one of the more disappointing ones. He is one-dimensional, simplistic, and rather shallower than his portrayal in both the manga original