Ani Zamba Chozom was one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Buddhist nun. Born in England in 1948, a serious illness as a teenager aroused in her a strong desire to benefit others. In search of answers to her confusion about life, in the 1960s she traveled overland to India, and has since practiced in many different countries and traditions. Today she lives mainly in Brazil, where her practical teachings, rooted in the simplicity of Dzogchen, are proving an inspiration to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. On a recent visit to Hong Kong, Frances McDonald interviewed her about her fascinating life, which will be published here on Buddhistdoor in eight weekly parts.*

Frances McDonald: Ani-la, could you tell us the story of when and how you encountered the Dharma?

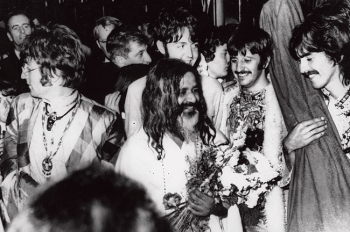

Ani Zamba: That’s quite a difficult question to answer. It was kind of a slow process. I went to India at the end of 1968, ‘69, looking for something that would help me make sense of my confusion. I started going around to all the well-known gurus at that time and listening to what they had to say, and seeing if I really could apply it to my own life. And basically, no, I didn’t get that kind of satisfaction.

FM: Were they Buddhist teachers?

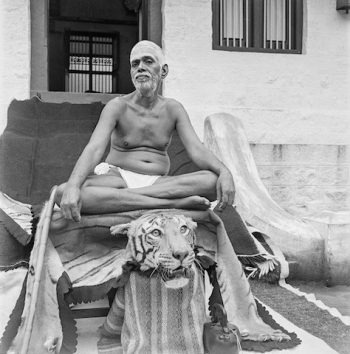

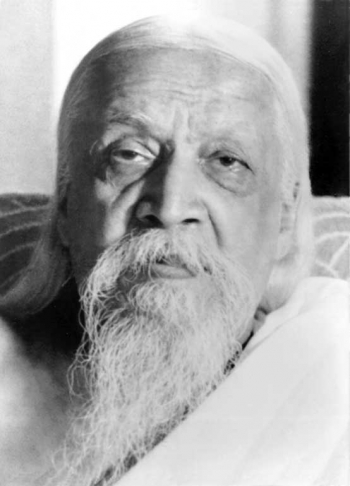

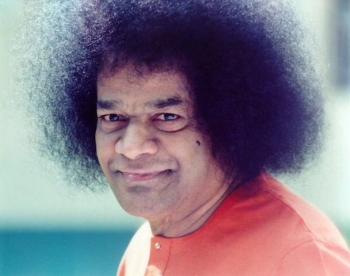

AZ: No, in the beginning it wasn’t Buddhist teachings, I didn’t have any connection with Buddhism in the beginning. This was more Hindu-based or Jain-based—different ashrams. I went from the north of India down to Madras then on to Ramana Maharshi’s ashram, and then Sri Aurobindo’s ashram, and then to Sri Lanka and then up the west coast of India over to Sai Baba, and then to other smaller temples and sannyasins. I would ask questions, but somehow nothing really touched me. I wasn’t into the devotional aspect, bhakti, and that seemed to be mostly what people were asking for—darshan, and all of this. My mind was a bit too scientific for all of that. I said, “Sorry, I can’t just believe like that. I need to question things. I need to understand how it’s going to work, how it can apply to the way I see life, how it can transform the way I see things.

FM: How did you know that the way you saw things needed transforming?

AZ: When I was young, I went through a kind of living death. I was paralyzed and in hospital for a long time. I couldn’t move any part of my body. I had plenty of time to think. In fact, first of all I just wanted to die. I didn’t want to go on because I couldn’t see any way of going on. There was no way that I could live just like a cabbage, waiting for people to turn me over or put food into the tubes that were feeding me. And then a friend who was dying of multiple sclerosis came to see me, and she said, “No, don’t give up! Think of something positive to do with your life if you recover.” I thought, “Something positive to do with my life? I can’t move! I can’t do anything! How can I think of something positive to do?” Then I said—even though I didn’t believe I would recover—“If I ever recover from this, I’ll give my life to helping others.”

FM: And you did recover.

AZ: They found a new drug, and I became one of the primary experiments for this. Slowly the feeling came back in the body, and I learned how to use my muscles again. I slowly learned to walk like a child and move, do simple actions. And I began to see things in a very different way. All my value systems were completely shaken up—I just didn’t have the same value systems as other people around me. I wasn’t interested in having things or relationships. I thought, “People don’t understand what they have; they don’t understand how wonderful it is to be able to put one’s fork from the plate to your mouth.” And I thought, “Maybe I could help people because I appreciate so many things that people don’t appreciate now. Maybe I can help them see the value of simple things.” Once I recovered, that was my kind of fundamental search—how to make my life useful in a way that could benefit others.

FM: Why India?

AZ: That was a kind of a gradual progression. I tried doing all kinds of things in the UK, running social clubs, working in underground newspapers, all kinds of things that I thought might be helpful in some way, but I saw just how futile my exploits were—yes, they brought temporary benefit to people, but they still remained dissatisfied, frustrated, and everything else. There were lots of problems. It was a time when people were taking lots of drugs, and the people I lived with were all arrested—the charge was trumped up, it wasn’t true—and it just became very difficult to live in the UK. Then an old friend came along and invited me to Cyprus. His daughter was close to me and was getting married in Cyprus. Once I got out of the UK I was so glad to get out of the environment I was living in, I thought, “Well, let’s try something new.” In Cyprus I took a job as a governess, and then I ended up running an open-air club and discotheque-restaurant as I had an extensive background in music. Then I went to Israel to study agriculture, and one thing kind of led to another. And then I went back to Cyprus, where I met an amazing woman. She had so many ideas about things, things that I’d never considered before—reincarnation, and so on. She opened me to different ways of thinking about things. And she said, “You know, we both need to go to India. We’re going to find a lot of answers in India.”