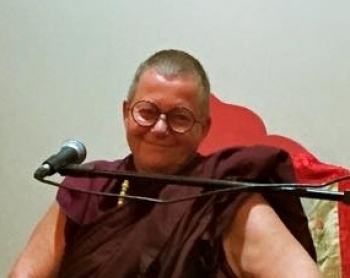

Ani Zamba Chozom was one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Buddhist nun. Born in England in 1948, a serious illness as a teenager aroused in her a strong desire to benefit others. In search of answers to her confusion about life, in the 1960s she traveled overland to India, and has since practiced in many different countries and traditions. Today she lives mainly in Brazil, where her practical teachings, rooted in the simplicity of Dzogchen, are proving an inspiration to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. On a recent visit to Hong Kong, Frances McDonald interviewed her about her fascinating life, which will be published here on Buddhistdoor in eight weekly parts.*

FM: So, you were pretty sick, and in 1978 Chagdud Rinpoche directed you to move to Thailand to spend time with the abbot of Wat Thamkrabok, who you met in 1975 and was a great healer.

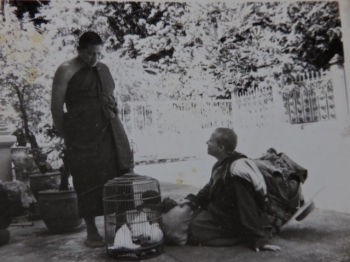

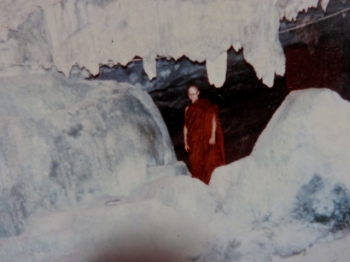

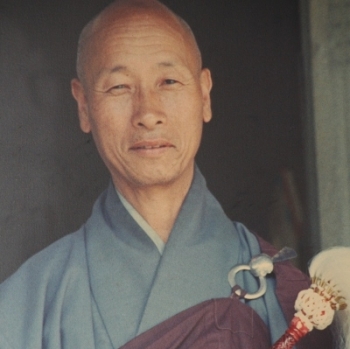

AZ: Chagdud Rinpoche’s advice to me was, “You don’t leave this abbot until he says you’re at least 95 per cent cured.” There I was, saying goodbye to Thinley Norbu Rinpoche, Chagdud Rinpoche, all my teachers, the Tibetan tradition—everything. And I arrived at this monastery in Thailand, which was a center for the cure of drug dependency. So Mother Teresa’s prophecy of me working with drug addicts was being fulfilled, ten years later. I lived there and worked there and practiced there. I lived in this cave-like situation up on a hill at the side of the monastery and set up programs for the rehabilitation center. I did lots of different things. My illness wasn’t cured yet—this was all during the process of being cured. The monk’s way of curing things was very unorthodox. Not only did I take the medicine that the addicts were taking, which was a detoxification for the whole system using over a hundred different kinds of herbs that make you vomit, but just being with this abbot . . . He’d take a glass of water and spit in it, and say, “Right, drink,” and that was all part of the cure.

FM: Did it work?

AZ: Yes. I don’t know how, but it worked! Slowly I began to get better, and got more involved in the center. I tried to initiate different things, and at the same time, carried on with my own practice. I stayed there doing various things, involving myself more and more in social projects, until the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia in 1979. And though I wasn’t completely better I felt strongly the need to be of help, so I said, “I’ve got to go, they really need people down at the Cambodian border. I think I can at least help a bit.” So he said, “You be careful!” Then I left and went down and helped set up the refugee camps along the Thai border.

FM: And then?

AZ: There was an incident in the camps where the Thai government was trying to send the children who were left alone in the camps to other countries—either their parents had been killed or, in their escape from Cambodia after the Vietnamese invaded, they had somehow been separated from their families. I was very against this idea as I felt we had not been given enough time to check more deeply where their parents might be, or if they were alive or not. So some doctors and myself tried to stop the cars from leaving the camps with the children and because of this, I was told that I would not be allowed to enter the camps any longer to help. This upset me a lot as I had taken responsibility for many children there. I then got very ill again and was sent back to the UK to recover. On my return I went back to the camps, but the situation had dramatically changed for the better, so I was no longer needed there to do the work I had been doing.

FM: So where did you go?

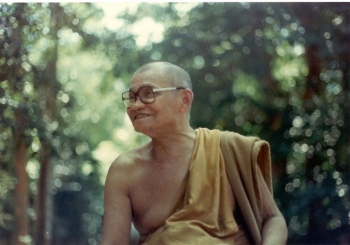

AZ: I began to travel. I wasn’t really well enough, but I felt I really wanted to travel in Thailand. I began to look at the different masters in Thailand, and went to visit Buddhadasa, to listen to his style of teachings. And then Ajahn Chah, a wonderful master in the northeast. I stayed with him and practiced at his Wat [temple]. At that time Ajahn Sumedho was there, Jack Kornfield was there, Joseph Goldstein, many people who have written books, and a few other teachers that people don’t know. I would go around and spend time in different communities and practice, and learn more about the Thai method of shamatha [calm abiding meditation], different skillful means. The Thais emphasize shamatha and vipassana [insight meditation]—very useful. I thought, “The Tibetans could do with more of this. As a basis it would be very helpful.” There’s not so much emphasis on shamatha in the Tibetan tradition.

FM: Did you decide to stay in Thailand?

AZ: No, I went into Burma—I decided I was going to go on a long walk. So I walked from Mae Hong Son, which is way up in the north of Thailand, all along the border of Thailand and Burma, until I came down to Three Pagodas Pass. And then illegally I went into Burma and lived in the forest with the tribes—mostly Mon at that time. These tribes supported me there. My motivation was to find out what was going on. I was looking at the source of the opium trade—I’d been working with the end product, which was all the people who were addicted to heroin. I wanted to see what was happening in Burma that perpetuated this trade, and if there was any way to bring in a kind of crop substitution program. A stupid idea—who’s going to walk days to buy strawberries, whereas they’ll walk for weeks to get the opium! The tribes used the opium more as a barter system. Half a kilo and they got all their rice, or 20 pigs—that’s how they survived. It was all about a way of living and surviving, not like when it came down to street level. So I stayed there for a while, and then after doing all that I decided I wanted more of a challenge in progressing along the path. In Thailand, women were not really seen as equals, and there were no women who I could really go to as examples, practitioners I felt that I could really learn from.

FM: But you hadn’t felt that to be a problem in Nepal or India, with the lamas?

AZ: No, I hadn’t found that at all. I was always stimulated by the teachings and the practice.