Ani Zamba Chozom was one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Buddhist nun. Born in England in 1948, a serious illness as a teenager aroused in her a strong desire to benefit others. In search of answers to her confusion about life, in the 1960s she traveled overland to India, and has since practiced in many different countries and traditions. Today she lives mainly in Brazil, where her practical teachings, rooted in the simplicity of Dzogchen, are proving an inspiration to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. On a recent visit to Hong Kong, Frances McDonald interviewed her about her fascinating life, which will be published here on Buddhistdoor in eight weekly parts.*

FM: So Lama Yeshe told you to go away and think about why you wanted to become a nun.

AZ: Yes. So I went back to England and really investigated why I thought becoming a nun was the best way for me to make my life useful and of benefit to others. Was there really a necessity to become a nun, to change my appearance? I thought about all the things I could do with my life—this, that, relationships, jobs, but I wasn’t interested in anything. Nothing could answer my nagging questions of “What’s it all about? Why am I here? Why did I go through all this?” After a few months in the UK, I went back to Nepal and told Lama Yeshe, “Now I know why I want to become a nun. I feel without any doubt—for me personally—I need that kind of commitment, that reminder of what I’m doing, of what I’m committed to doing in this lifetime and why.”

FM: Do you mean in terms of the vows?

AZ: Both the vows and the robes. Taking robes is in itself quite a deep commitment to practice—that you value the discipline as a support to help you along the path so that you can see more clearly and slowly have the ability to make your life of benefit to others, in order to have the skillful means to be able to help other people liberate themselves. You can’t liberate them—you can never save anybody—but if you have the tools and know how to use them you can then help others to liberate themselves. You can show them how the path works, and how they can work with their own neurotic habits and tendencies to free themselves.

FM: Did you take the novice vows right away?

AZ: No, I started with taking the eight precepts every morning, and then slowly this kind of discipline becomes more natural, you have less tendency to want to lie, steal, kill, or harm others in any way. You begin to live in that kind of discipline—it makes you more mindful. Whenever there is a tendency to act in a way that’s harmful, something stops you and you reconsider your action. You may usually be on automatic pilot, which makes you go over to that mosquito and maybe want to get rid of it, harm it. So now, instead of seeing it as a threat in some way, you want to protect it. You have the space—your discipline makes you reconsider your usual habit of trying to maintain your own comfort zone. You think more about the other being. And you don’t feel the need to be dishonest. There’s no reason to lie any more—there’s nothing to protect.

FM: Did Lama Yeshe give you ordination himself?

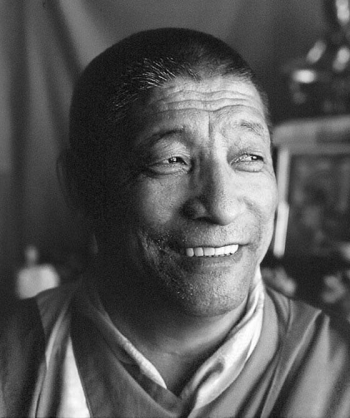

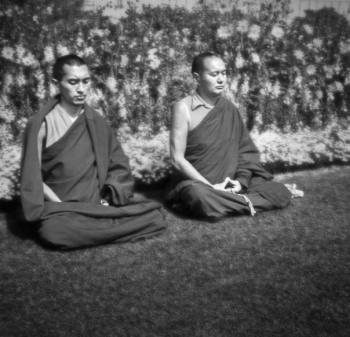

AZ: When I explained to Lama Yeshe my motivation for becoming a nun, he considered whether it was true, whether it was really coming from my heart. And he said, “I won’t give you ordination myself, I’ll take you to my teacher in India—Geshe Rabten.” So I went to Geshe Rabten, who was one of the main advisers to HH the Dalai Lama and a great scholar and practitioner himself. When it came time for the actual ordination ceremony he called down five of the yogis who lived above McLeod Ganj, who were His Holiness’s personal yogis so-to-speak. HH the Dalai Lama really took care of them, he sponsored them. They’d been up there years and years in retreat—incredible beings. Geshe Rabten called the five principal yogis down to be part of the ordination.

FM: Ordination was pretty unusual for Western women in those days.

AZ: Yes, there were very few Westerners around at that time. Lama Yeshe was there for the ordination—this was the novice ordination of 36 precepts. My hair was formally shaved, although I’d already cut it off, and I was given my full set of robes—specific kinds of robes I had to wear in certain ways from then on. That was the beginning of my monastic life.

FM: Did you stay in McLeod Ganj?

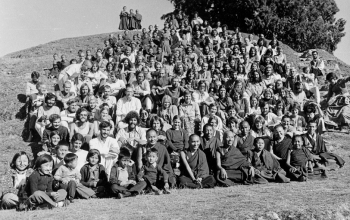

AZ: No, I went back to Nepal, but it wasn’t really working for me living at Kopan. I wanted to be in retreat, so I went off down the valley away from Kopan, where the numbers of people were increasing. I wasn’t into the group aspect at all, I just wanted to be in solitary retreat. Off I went to this wonderful Vajrayogini shrine I found. It was in somebody’s house—actually in a largish barn.

FM: Had Lama Yeshe given you a practice?

AZ: Not as yet. I was doing what I thought I should be doing, which was offerings to Vajrayogini and basic practice. I would kind of meditate—my idea of meditate—at least sitting still and stilling the mind a bit. Studying my Dharma books. But that was not Lama Yeshe’s idea for me! He found out where I was—even though it was a long way from Kopan—and he sent a monk down the valley to find me. There was a knock on the door: “Lama Yeshe says you have to come back and give a public talk this weekend.” “No,” I replied. “I’m just going to stay