FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

The Many Forms of Avalokiteshvara

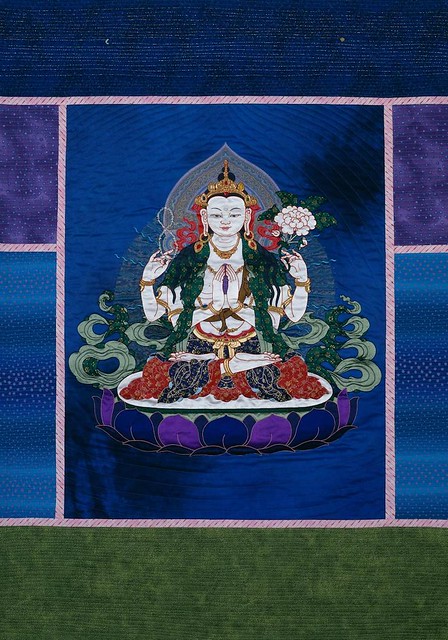

Chenrezig by Leslie Rinchen Wongmo. Pieced silk thangka, 2000.

Image courtesy of Leslie Rinchen Wongmo*

To many practitioners of the Mahayana schools of Buddhism of East Asia and the esoteric traditions of the Himalayas and Japan, bodhisattvas, or “enlightenment beings,” hold as much importance in daily practice and beliefs as Shakyamuni Buddha himself. Unlike the Buddha, who attained enlightenment and then transcended the human realm, bodhisattvas are said to have postponed their own enlightenment, or nirvana, to remain in this world to help other sentient beings attain enlightenment. Of the many bodhisattvas in the Buddhist pantheon, the most widely revered is Avalokiteshvara (meaning “the lord who gazes down”), a compassionate being who is believed to possess the ability to look in all directions to see who is suffering and to offer salvation. One of the most fascinating figures in Asian Buddhist imagery, Avalokiteshvara is represented in a multitude of forms, from a simple princely bodhisattva holding a lotus, to a complex, multi-armed deity, and even a mother holding a child. In recent years, this bodhisattva’s presence has extended beyond the realm of Buddhism and into areas of secular life.

Avalokiteshvara’s devotion to helping others is understood to be limitless, and to many Buddhists he is seen as embodying the compassion of all Buddhas. According to certain Buddhist texts, the deity took a vow to postpone his own enlightenment until all blades of grass and grains of sand have become enlightened; only then will he transcend this material realm to become a Buddha. In the Lotus Sutra, a text revered by many practitioners throughout East Asia, the deity is the subject of a whole chapter, which describes him as possessing many different powers and the ability to assume many forms in order to share the Buddha’s teachings and relieve the suffering of followers. This colorful description accounts for his diverse representations in Buddhist imagery. In many paintings and sculptures, Avalokiteshvara is shown in the typical garb of a bodhisattva, a prince-like figure wearing robes, a crown, and jewelry (to symbolize his presence in our material realm). Avalokiteshvara can be distinguished from other bodhisattvas by the lotus he holds in one hand, symbolizing the potential in us all to attain enlightenment (just as a pure lotus can grow in the muddiest water). He also typically wears a small image of Amitabha Buddha (or Amitayus), in his crown, representing his spiritual association with this particular Buddha.

In China, the deity is known as Guanyin, and for several centuries has been depicted in both male and female forms. The fluid gender of this deity in a number of Buddhist cultures has been the subject of copious research in Asia and beyond, but may best be explained as a consequence of his freedom to assume any form to respond to the many needs of followers. Many Chinese Guanyin figures have a graceful feminine appearance, but are either considered male or without gender. However, from around the 12th century onwards in China, the deity became associated with a princess named Miaoshan, a figure in an ancient tale who demonstrated tremendous compassion. From this period, female figures of Guanyin became very popular, with some renderings depicted the deity with prominent breasts and cradling a baby, representing her power to give and protect children. With the arrival of Jesuit missionaries in southern China in the early 17th century, these images of Guanyin became associated with images of the Virgin Mary and the baby Jesus, and Guanyin became known in the West as the Buddhist “Goddess of Compassion,” or “Goddess of Mercy.”

Detail of the Thousand-Armed Avalokitesvara by Shashi Dhoj

Tulachan, Tibet, c. 2010. Image courtesy of the Bowers Museum,

Santa Ana, CA

One of the bodhisattva’s most powerful and complex forms has 11 heads and 1,000 arms. This form of Avalokiteshvara is portrayed most often in the esoteric traditions of Tibet and Japan. The heads represent his 11 principal virtues (including non-attachment, non-violence, and faith), which he uses to conquer the 11 desires that obstruct the path to enlightenment. Avalokiteshvara’s 1,000 arms symbolize his many powers, which he uses to save all beings and lead them toward enlightenment. The central pair of arms is shown in a gesture of prayer, and the outer arms hold many different attributes, including weapons that represent the various ways in which he can offer help to his followers. The hands are often adorned with eyes that signify his omniscience and ability to see in all directions to identify suffering. To Vajrayana Buddhists, Avalokiteshvara (or Chenrezig), has particular significance in all of his forms and is considered the patron deity of Tibet, watching over the Land of the Snows. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is believed to be an incarnation of this bodhisattva and, as such, a living symbol of infinite compassion.

In Japan, Avalokiteshvara (or Kannon), has been one of the most influential Buddhist deities. Because Japanese Buddhism includes devotional sects, esoteric practices, and Zen meditational Buddhism, it is perhaps in Japan where images of Avalakiteshvara are most diverse, and have long been depicted in paintings, cast in bronze, sculpted into stone, and carved out of wood, coated with lacquer, and sprinkled with gold powder. In the Zen tradition, which usually rejects iconic imagery, the deity has been the subject of many monochrome brush paintings and is a reminder of the importance of compassion. In these paintings, the deity is often depicted with a playful or mischievous expression.

One of the most surprising depictions of the Avalokiteshvara dates to 1934. In 1930, two Japanese brothers, Goro and Saburo Uchida, founded a company that specialized in precision optical instruments. Four years later, they created their first camera, which they named the Kwanon, after the deity Kannon, presumably because of his association with flawless, precise vision. Their logo featured a simple black-and-white image of Kannon with 1,000 arms. In 1947, the company’s name was changed to Canon, and the Buddhist logo was dropped. Despite fluctuations in Japan’s economic circumstances, the company remains one of the country’s largest public companies to this day. Inspired by the most compassionate of all Buddhist deities, the name was an auspicious choice indeed!