FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

The Monks and Mandalas of Ato Sengai

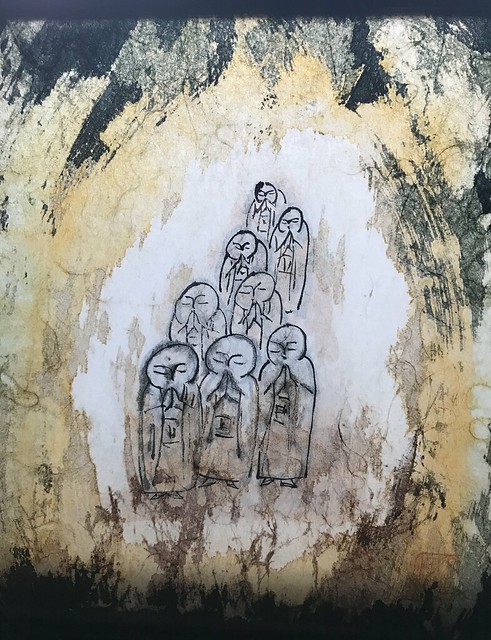

Procession of Monks by Ato Sengai, Japan, c. 1970.

Ink and color on paper. Image courtesy of the author

For more than a decade I have owned a small painting that I adore but know very little about. It depicts a group of Buddhist monks walking in procession toward the viewer, three in the front row, followed by a row of two, then another two, with a single monk bringing up the rear. The shaven-headed monks are drawn simply in black ink, with slender lines denoting their long robes, closed eyes and eyebrows, and hands held in prayer before their mouths. Such arrangements of Buddhist monks are not uncommon in 20th century Buddhist paintings, especially those of the Zen tradition. The well-known Japanese monk-artist Nakahara Nantembo (1839–1925) depicted similar processions of monks, with and without hats and staffs, in black ink on white paper. What is unique about this painting is that the figures are framed with splashes of yellow, brown, and black ink, and is rendered on paper so thin that the painting can be viewed from both sides.

This humble but delightful image is the work of a Japanese Buddhist monk called Ato Sengai, who was born in Japan in 1929 and died in 1996. According to Allison Tolman of the Tolman Collection of Tokyo, he was from Kyushu and created many silkscreen prints of Buddhist subjects. His prints are part of the Sosaku-hanga, or creative woodblock prints tradition in which artists were involved in all stages of the designing and printing process—in contrast to the more traditional Japanese woodblock prints of the earlier ukiyo-e tradition that were a team effort involving a publisher, designer, block-carver and printer. Although many Buddhist monks and priests, especially in the Zen Buddhist tradition, created paintings and wrote calligraphy as teaching tools to spur their disciples on to enlightenment, fewer Buddhist artists have used woodblock or silkscreen printing to express their spirituality or to represent Buddhist themes.

Mandala by Ato Sengai, 1970. Screen print, 62.5 x 54 centimeters.

Collection of the University of Maryland Art Gallery, gift of Mary Spellman Tolman and

Norman H. Tolman. Image courtesy of the University of Maryland Art Gallery

Ato, however, seems to have mastered the technique of silkscreen printing—a method of creating an image on paper, fabric, or some other medium by pressing ink through a screen with areas blocked off by a stencil. He used the technique to create a number of simple yet powerful prints that present traditional Buddhist subjects using a highly contemporary, often abstract approach to design, composition, and color. In a work entitled Mandala in the collection of the University of Maryland Art Gallery, Ato evokes Buddhist mandalas—geometric diagrams that represent the sacred realms of enlightened beings. In this print, concentric circles in bold colors surround a central flame or lotus petal, suggesting a Buddhist deity with a halo. Above the circular mandala is a bold, red semicircle form that may represent a monk’s begging bowl. In another image in the collection of Seattle Art Museum, Ato used screen printing to create a semi-abstract design of a two-wheeled mandala (Japanese: nirin mandara), in which two vivid orange circles filled with vibrant patterns intersect each other. Both images representing the Buddhist universe and likely used for meditation, date to the early 1970s.

Untitled (Mandala) by Ato Sengai, Japan, 20th century.

Printed with dye on paper, 25-1/8 x 19-1/4 inches. Los Angeles County

Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. James Nathan.

Image courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Another silkscreen print in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art also depicts a Buddhist mandala, but in this case, the mandala is more elaborate and floral, based on the Buddhist motif of the lotus flower, which symbolizes the potential within all beings to attain enlightenment. Using bold reds, yellows, and greens, rather than the more Western bright turquoises and cool greens of the semi-abstract mandalas, Ato seems to be looking back to South Asia and the roots of the Buddhist tradition.

Procession of Monks by Ato Sengai, Japan,

c. 1970s. Ink and colors printed on paper.

From worthpoint.com

Ato used such vivid, hot colors in one more print that I am familiar with, another Procession of Monks probably also dating to the 1970s. In this work, the artist again depicted a group of seven monks descending toward the left—this time wearing straw hats and carrying begging bowls. Here, though, the monks are outlined in white (created with a resist) and surrounded by a fiery halo of vivid yellow and orange. Somewhat ironically—and very sadly for this fan of Ato Sengai’s work—I lost this print several years ago in a fire that destroyed part of my home. I imagine that much of the work by this little-known but very gifted Buddhist artist was created to teach important Buddhist lessons to his followers and students. Although I never met him, loving and losing one of his works of art taught me a powerful lesson in impermanence, and it makes me value the painting that I still have all the more.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Butsuzо̄ in the Shell: The Buddhist Sculptures of Takuma Kamine

Buddhist Sensibilities in the Printmaking of Ayomi Yoshida

Power and Beauty: Robert Wilson Takes On the Last Dynasty