FEATURES

The Sensitivity of a Mother

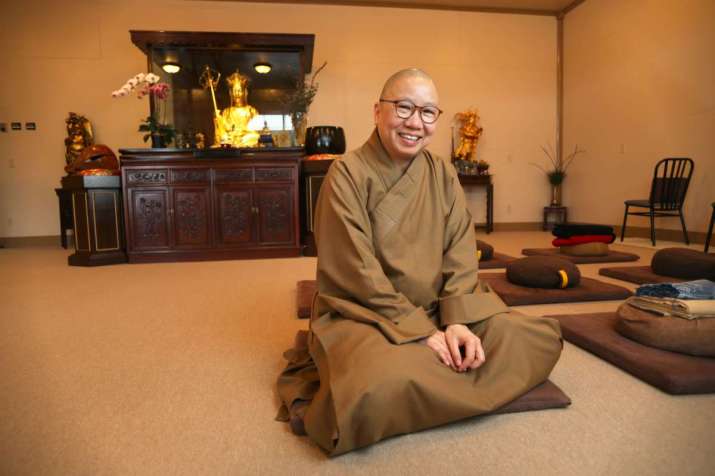

Venerable Yin Kit. Photo by Greg Laychak

Venerable Yin Kit. Photo by Greg LaychakComing to the Canadian west coast as a young Buddhist nun from Hong Kong was not unlike being a new mother, pregnant for the first time. Except the baby I was carrying within me was the responsibility of spreading the Dharma in the West.

Arriving in Canada 24 years ago, all my experiences were so new. Ordained just two years earlier, I arrived in a small town of about 40,000 people, in the “Bible Belt” area of the Fraser Valley in British Columbia. There were easily 65–70 churches, sometimes four at one intersection. I felt like an alien dropped into an unfamiliar and unreceptive world, carrying a precious baby, not knowing how the baby really was. Was it healthy? Was it still alive? Was I carrying it correctly? There was no way to know. But I was aware of a developing sensitivity.

Carrying such a heavy responsibility with my fellow nun who accompanied me to Canada, we naturally worried about the future. But even new mothers know that worrying will not help her child. So, we focused on providing the right food for the growing child. Whatever immediate responsibilities we faced, we dealt with in the moment. Just as a young mother receives the advice of her elders on how to take care of the unborn baby, we received teachings and advice from our elder monastics. Whatever our seniors taught us, we respected and tried to put it into practice.

Our shraddha, or faith and trust, in the Dharma, in our teachers, and in ourselves was so very important. We trusted that we were trying to nourish the baby with the wonderful teachings. We did not know whether we would be able to fulfill the mission, but we had faith that we just needed to give our best efforts on this path and the Dharma would take care of itself.

People would come; people would go. At times, there were differences in opinions and views, and these differences would present challenges. But these challenges would also provided an internal nourishment for the growing baby. We would constantly remind ourselves to return to the teachings, to the path, to awareness, and deal with all the worrying and questions and difficulties one step at a time. We were like a young mother who does her best to maintain a sound mind for her unborn child, so that the child is not affected by her emotional stress.

And just as a mother may notice that certain foods or exercises are not suitable for the unborn child, we began to gradually realize that our traditional practice was not always suited to people in the West. A mother must be perceptive in order to notice any upheavals or challenges the baby faces. She must make the right adjustments at the appropriate time. Like the growing sensitivity of a young mother, we began to develop a deeper sensitivity to the needs of the people we encountered here. In the beginning, we were trying to use the traditional Mahayana practices that we had learned in Hong Kong. But when we became more sensitive to how receptive the outside world was, we began to understand that people in the West were brought up, educated, and interacted with Western religion in an entirely different way. We realized that they may need something different.

We questioned and thought deeply on this. What is the best way to fulfill our responsibility; to look after this child in the womb? Gradually, because of the great blessings from the past teachers, we were able to find ways to fulfill our mission. By the time our baby was born, we had found a path to spread the Dharma in the West. The baby was still very immature, very fragile. Today, we continue to grow and learn and to apply constant reflection, consideration, understanding, and clear communication with our congregation members. Developing sensitivity toward the people who come into this space, the Dharma space, and to understand what their needs are, is indeed crucial. We realized that it is not about what we want to give them, but about what they need or require.

Of course, everyone has the same fundamental need and requires that medicine; to be liberated from suffering. Yet everyone carries their own karma. And how are we going to give that medicine? What kind of medicine are we going to give them so that people become healthier, and maybe even able to look for the medicine themselves, take the medicine themselves, and even learn how to grow their own medicine one day?

Developing this sensitivity is challenging but very rewarding. How can we know how this baby is growing and, when it is born, how can we nourish it? When opportunities come, how do we take up the responsibility and devote all the energy, compassion, faith, and efforts, totally and completely onto the path of Dharma?

Once this child was born, we had to be continuously diligent, objective, and determined to take care of this growing child. We continued to be very open-minded and flexible to change according to the needs of the people we encountered, but also diligently keeping up the practice of morality, concentration, and wisdom ourselves. As a Chinese Buddhist woman in the West, I have learned to be more objective, patient, and humble. This helps to really brush down the ego and allow me to effectively listen and to observe from a wider perspective, and to empathize with greater understanding, sowing the seeds for more people to learn the Dharma, to experience the teachings, and to change for the better.

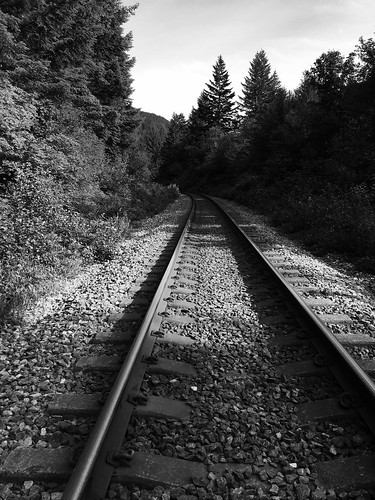

“Follow the right path home:” Po Lam, Chilliwack, British Columbia. Photo by Venerable Yin Kit

“Follow the right path home:” Po Lam, Chilliwack, British Columbia. Photo by Venerable Yin KitThe Buddha said it is very important for us not to take his words blindly but to experience his teachings personally, and then come to adopt those words as the way to live our lives. That direct experience is the way to help us to come out of difficulties and to reach the goal of becoming wise, happy, free, and compassionate. This, I believe, is the true conversion, an insightful and freeing conversion of the internal qualities.

As a Buddhist nun in the West, I have learned that we need to address these needs with sensitivity, respect, and compassion, just as a mother would wholeheartedly and selflessly care for the needs of her child.

Buddhistdoor Global Special Issue 2018