FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

The Tree in Buddhist Symbolism and Art

For millennia, trees have occupied an important symbolic place in many of the world’s religious traditions, often representing the essence of life or a link between the human realm and that of the sacred. In the Buddhist tradition, a number of different trees play a critical role in the life of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, most notably at the moments of his birth, his enlightenment, and his death. In particular, the site of the tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment, a pipal tree in Bodh Gaya, India, is still revered today as the locus of his spiritual awakening. Because of its powerful spiritual symbolism, the tree also figures prominently in Buddhist imagery. Unlike many other aspects of Buddhist art and iconography, trees are not depicted using specific rules and can vary greatly in their representation according to the regional styles employed; however, their symbolism as a bridge unifying the material and the spiritual is unchanging.

According to Buddhist legend, Queen Maya, the mother of the prince who would later become the Buddha, Prince Siddhartha, gave birth to him in a miraculous manner in a grove of trees in Lumbini. When she knew that her time was due, she grasped a teak tree with her right hand, and the baby emerged from her right side. This tree is represented in both painted and sculpted scenes of the life of the Buddha, as in a fine Gandharan panel in the collection of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. In this carving, Queen Maya is depicted in the very sensual and elegant Indian triple-bend (Skt. tribhanga), or S-shaped, pose, and is surrounded by ladies-in-waiting on her left and male attendants on her right. Her arm is shown reaching up and grasping one of the curvaceous leaves of the tree above her, and from her right side emerges a miniature, fully formed figure of the Buddha. Since the scene represents a legendary moment, its symbolism is far more important than a sense of realism. The leaves of this tree more closely resemble the acanthus leaves of Greco-Roman sculpture than the simple oval leaves of a teak tree.

Scene of the Birth of the Buddha. Gandhara, Kushan dynasty, late 2nd–early 3rd

century, schist. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

From commons.wikimedia.org

The young Prince Siddhartha grew up in a life of luxury, but around the age of 30 left his palace life behind to discover the truth about life and suffering, a journey that again led him to a tree. According to Buddhist tradition, although he studied for years under various spiritual teachers, he was unable to attain the spiritual enlightenment he sought until he arrived in the place now known as Bodh Gaya, where a pipal tree (L. Ficus religiosa) had (supposedly) sprouted on the day of his birth. Somehow he recognized the tree, and sat down beneath it to meditate until he attained spiritual release. He is believed to have remained under the tree in a state of deep meditation for several days before achieving nirvana and becoming the Buddha. Thus the tree also became known as the Bodhi tree, or the tree of enlightenment. The moment of the Buddha’s awakening under this tree is portrayed in painting, sculpture, and manuscripts, particularly in Southeast Asia. A Thai Buddhist sculpture from the Mon-Dvaravati period (7th–9th century) shows the Buddha seated peacefully in full lotus position beneath the generous canopy of the tree. As in most depictions of the Bodhi tree, the leaves have the highly distinctive, heart-shaped leaves of the real pipal tree.

The Buddha Seated under the Bodhi Tree. Thailand,

Mon-Dvaravati period (7th–9th century), terracotta. The

Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Gifts of friends of Jim

Thompson, in his memory, 1991. From metmuseum.org

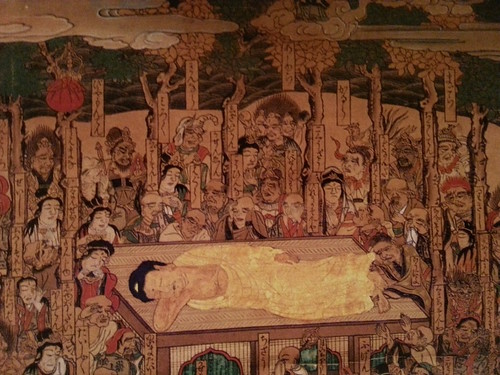

The final moments of the Buddha’s life are also represented under trees. When the Buddha was aged 80 or 81, he is believed to have suffered from food poisoning and retreated to a grove of sal or sala trees (L. Shorea rubusta) in Kushinagara in modern Bihar. He advised his closest disciple Ananda to position him with his head to the north between two of the trees. There, lying on a bed and surrounded by his faithful disciples, he passed away and entered the state of final enlightenment, or parinirvana. In many sculptures depicting the Buddha’s passing the trees are not represented, but in paintings of this scene, which are popular in Japanese Buddhist iconography, his deathbed is surrounded by tall, slender sal trees with gold or yellow leaves.

Death Scene of the Buddha (detail). Japan, Edo period (1600–1868), hand-

colored woodblock print on paper. Image courtesy of Sam Fogg, London

Trees appear in other aspects of Buddhist art as well, including scenes of the Buddhist paradises, in which they are depicted laden with jewels, representing the spiritual wealth of those progressing towards enlightenment. There is also a tree, the Rose-Apple Tree, on the summit of Mount Meru at the very center of the Buddhist cosmos. This tree serves as a cosmic pillar connecting Heaven and Earth. Considering the central role of the tree in the Buddhist cosmos, it is not surprising that trees are central in the life and legends of the Buddha and his enlightenment and that they connect his material existence to his spiritual one. When the Buddha was born, he assumed his human, material form; when he attained enlightenment, he achieved a higher spiritual level; when he died, he shed his physical form and fully entered the spiritual realm. A tree was present at each of these moments, serving as an arboreal bridge between our material realm and enlightenment.