FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

The Universe in a Dot of Paint: The Buddhist Imagery of Sherab Khandro

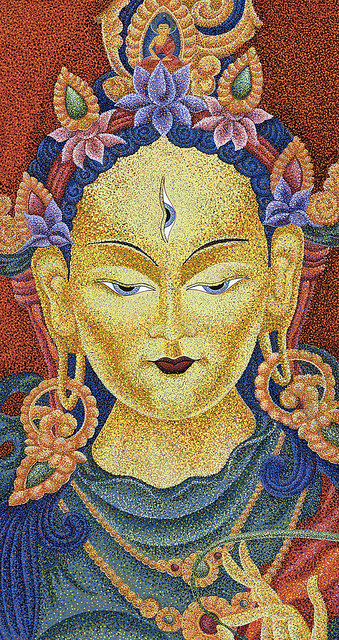

Red Tara: Tara of the Bodhichitta by Sherab Khandro, 2002. Limited edition giclée print, 26x34 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Goldenstein Gallery, Sedona, Arizona

Red Tara: Tara of the Bodhichitta by Sherab Khandro, 2002. Limited edition giclée print, 26x34 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Goldenstein Gallery, Sedona, ArizonaWhen we think of Pointillism, we think of paintings created by French Impressionist artists such as George Seurat (1859–91) and Paul Signac (1863–1935). In Pointillist paintings—like Seurat’s celebrated A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–86)—artists apply thousands of separate dots to a canvas in specific patterns and the dots of color in the finished image blend optically rather than physically, in contrast with more traditional painting styles, in which colors are blended on the palette before being applied to the painting surface. Pointillism has appeared more recently in the work of renowned artists such as Andy Warhol (1928–87) and Chuck Close (b.1940), whose “faux-pointillist” works reference the pixilation of contemporary digital imagery. American artist Sherab Khandro has brought this technique into the realm of Buddhist imagery. In her extraordinary Buddhist paintings, the application of tiny specks of color to the canvas is not simply an exploration of the effect of optics on color perception, but also of the effects of her Buddhist and artistic practice on the world at large.

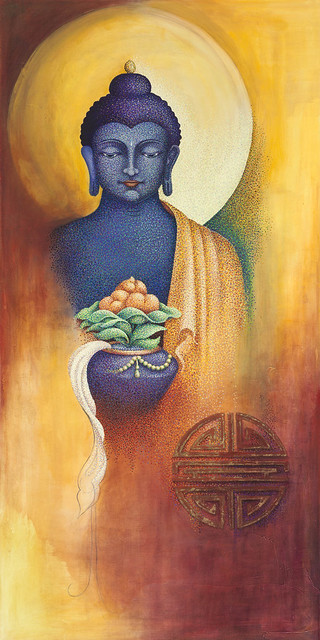

The Lotus King: Padmasambhava by Sherab Khandro, 2003.

Acrylic on board, 60x48 inches. Image courtesy of the artist

and Goldenstein Gallery, Sedona, Arizona

Based in Sedona, Arizona, Sherab “Shey” Khandro has been creating Buddhist paintings, sculptures, and jewelry for more than 25 years. Viewing her paintings from a distance, it is clear that Khandro has mastered the skill of rendering Buddhist deities with the iconographic and iconometric precision required in Buddhist devotional imagery. Yet she achieves this using the Western pointillist technique, rather than with a traditional Buddhist painting method. Her painterly skill is apparent in her spectacular representation of Padmasambhava, or Guru Rinpoche, the 8th century Indian Buddhist master credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet. The image of the Lotus King, depicted seated on a lotus, one foot outstretched in a motion of readiness to help others, features highly precise detailing—created using hundreds of tiny dots of color—while also possessing a soft luminescence that heightens the sense of divinity emanating from the Buddhist master.

Mother Tara: Angel of Peace by Sherab Khandro,

2000. Acrylic on board, 18x34 inches. Image courtesy

of the artist and Goldenstein Gallery, Sedona, Arizona

Her technique also lends a spiritual depth and warmth to her paintings of powerful female deities. In her depictions of the various forms of Tara—the bodhisattva said to be born from the compassionate tear of Avalokiteshvara—she not only represents the compassionate deity with the postures, colors, and decorative elements seen in traditional Buddhist paintings, but with a gentle hazy glow that suggests warmth, comfort, and trust. Her image Mother Tara is particularly radiant, the result of the texture built up using many hundreds of dots. This glow rises to an intense burning in her depictions of lively and often wrathful deities like dakini—dynamic female spirits who feature prominently in Tibetan Buddhist imagery. In her work, Vajravarahi: Dance of the Red Dakini, the divine energy exuded by this being is expressed in a dynamic halo of flames that rises up around her, with extra luminescence created by the build up of dots.

Vajravarahi: Dance of the Red Dakini, by Sherab Khandro,

2005. Acrylic on board, 60x48 inches. Image courtesy of

the artist and Goldenstein Gallery, Sedona, Arizona

Khandro’s success as an artist undoubtedly relates to her deep grounding in traditional Tibetan Buddhist teachings as well as her extensive study of Buddhist iconography and artistic techniques. At the age of 30, Khandro (the Buddhist name she took when she became ordained) took the very unusual step for a young woman in Maryland of becoming ordained as a nun with a local Tibetan Buddhist community, Kunzang Palyul Chöeling. For the next 15 years, she lived in the monastery and studied with exiled Tibetan Buddhist teachers, becoming versed in Buddhist teachings as well as ancient and modern metaphysics and physics, and practicing daily meditation. Although she renounced the material world, she and her fellow adepts were surrounded in the monastery by the beauty of sacred Tibetan Buddhist paintings and sculptures that were displayed during rituals and used for visualization practices.

While at the monastery, Khandro not only nurtured her spiritual self but also became aware of her artistic abilities. “My spiritual teacher helped me give birth to my heart,” she explains. “And it was there I found the artist.” At the monastery, she recounts, “I would practice drawing and painting as I began to study sacred imagery with the visiting Tibetan monks. However, most of my artwork at that time was focused on sculpture. I was very involved in building stupas [Buddhist reliquaries].”

When Khandro left the monastery in 2005, she chose to pursue a career as an artist. Her goal was to create spiritual imagery, but rather than follow traditional Tibetan Buddhist painting techniques and styles, she adopted the Neo-Impressionism style of pointillism in her paintings—a style previously unknown in the Buddhist art world. She encountered the painting technique in a color class while studying art at a local college during her early years as a nun. “Our final project was a small pointillist painting,” she recalls. “I chose a devotional image and as I sank into my painting, the colors and the distinctness of each moment as the brush touched the canvas took me into an offering meditation. I found myself filled with gratitude, all the vibrant colors playing off of one another, each moment, each stroke of the brush an intersection of time and space offered for the benefit of all. I was hooked by this practice.” Although much of her early work as an artist focused on sculpture, she felt called to paint after moving to Sedona in 1998, and has been in love with this painting technique ever since.

For Khandro, the process of manifesting these images out of dots of paint is as important as the final image itself. In every Buddhist painting she creates, she is manifesting a prayer, making a visual offering. With each stroke of the brush, she offers to the world a prayer of compassion. Each dot is a jeweled universe, offered as a prayer to the Buddha to end suffering in the world. “It is a meditation,” she reveals. “I feel expanded and purposeful as I paint. I feel connected to all living beings, to my vow as an aspiring bodhisattva, and to the real possibility of a world free of suffering. I feel joyful and loving.” Although this painting process has its roots in European artistic experiments, the act of applying thousands of tiny colored dots to a surface as an act of meditation and a prayer for love and peace is not entirely unfamiliar to Tibetan Buddhists. In many ways, the process is akin to the tradition of creating sand mandalas, the brightly colored Buddhist diagrams that are formed by sprinkling thousands of grains of colored sand into an intricate outline onto a flat surface. For the monks who spend many hours rhythmically sprinkling the colored sand, each grain is also an offering and a prayer for peace. Like Khandro, they are engaged in a powerful act of meditation in the hope that the spiritual energy and prayers generated through the process will spread love, compassion, healing, and peace in the world. With both of these painstakingly intricate art forms, the Buddhist artists creating them are infusing each grain of sand or dot of paint with such impassioned prayers that when we view the final image, not only are our eyes moved to blend colors together but our hearts cannot help but be stirred too.

Our Time is Now by Sherab Khandro, 2017. Acrylic

on canvas, 24x48 inches. Image courtesy of the

artist and Goldenstein Gallery, Sedona, Arizona

Sherab Khandro works in Sedona, Arizona, and is an artist in residence at the Goldenstein Gallery. More about her Buddhist paintings, limited edition prints, sculpture, jewelry, talks, and guided meditations can be found at sherabkhandro.com.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Bull-headed Wrath: The Propagation of Daiitoku Myōō Iconography

Fabiana Nakano: Expressing Self and Universe Through a Contemporary Mandala

An Eye, a Lens, a Dance