FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhism in Japan

The Zen Masters of the Rinzai Tradition

Today, I would like to begin a series of essays on Zen masters within the various Zen Buddhist traditions in Japan. Specifically, I will focus on some of the famous Rinzai masters. However, neither the list nor the descriptions are intended to be comprehensive but are designed to create an interest in these fascinating spiritual leaders and role models. In Japan, temples and pilgrimages commemorate the lives and teachings of these figures. Today, I will introduce Bankei Yōtaku, Hakuin Ekaku, Ikkyū Sōjun, and Takuan Sōhō in alphabetical order.

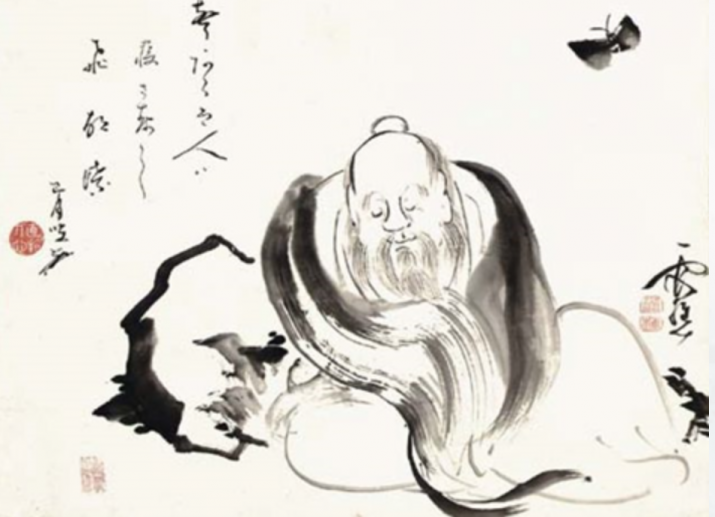

Born in the town of Harima Hamada, today’s Himeji in Hyōgo Prefecture, Bankei Yōtaku (1621–93) is said to have been intrigued by the phrase “luminous virtue” (Jap: myōtoku) when he read the Confucian classic Great Learning (Ch: daxue) at the age of 12. At age 17, Bankei began to train under the Sōtō Zen master Unpo (d. 1719) at Zuiō-ji and attained enlightenment nine years later when he heard the phrase “the mind of the Buddha is without birth” (Jap: busshin fushō). But it was only when he met the Chinese Chan master Daozhe Chaoyuan (Jap: Dōja Chōgen) that he understood the phrase and developed what is known today as “unborn Zen” (Jap: fushōzen). During his active time, Bankei taught at various temples, such as Myōan-ji and served temples like Henshōan. He passed away in 1693 in the temple Ryūmon-ji, which was built under his supervision, and received in 1740 the posthumous name Daihō Shōgen Kokushi.

Bankei Yōtaku. From somathread.ning.com

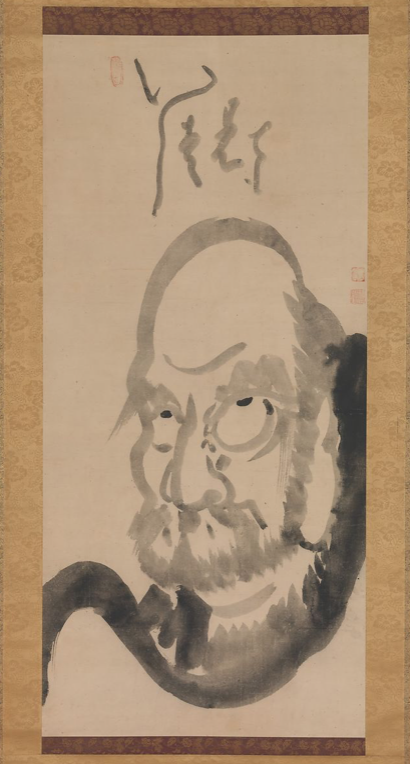

Bankei Yōtaku. From somathread.ning.comHakuin Ekaku (1686–1769) is arguably the most important monk of the Rinzai school of Buddhism and one of the most colorful figures in Japanese Buddhism. Born in Hara in impoverished circumstances, he became religious when the crackling of the fire used to heat the bath water reminded him of the descriptions of hell he had heard from his mother. To alleviate his extreme fear of hell, Hakuin began to chant the name of the Lotus Sūtra (Jap: namu myōhō rengekyō) and to worship the major deity at the Kumamoto Shrine. Disillusioned by the lack of efficacy of both practices, Hakuin turned to Zen Buddhism and studied at Eigan-ji. He continued his post-enlightenment practice under Shōju, who famously twisted Hakuin’s nose and called him a “hole-dwelling devil.” Hakuin’s journey toward enlightenment was arduous and violent, and on this journey he endured the abuse of his master and suffered what he would later call “Zen sickness” (Jap: zenbyō). Hakuin cured his sickness with the help of visualization techniques that he learned from the itinerant Daoist hermit Hakuyu, and suggested later in life that Zen sickness can aid the attainment of enlightenment since it takes the attention away from the self. He finally settled down at Myōshin-ji and made a name for himself because of his systematization of kōans (Ch: gongan) and their fivefold categorization. Both his experience with Zen sickness and his emphasis on kōan reverberated his belief that it was only the “great death” (Jap: daishi) caused by “great doubt” (Jap: daigi) that could finally lead to “great enlightenment” (Jap: daigo). His most important works are Yasen Kanna (Evening Conversations on a Boat) and Orategama (The Embrossed Tea Kettle).

Hakuin Ekaku. From metmuseum.org

Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481) is one of the most well known and controversial Zen masters of Rinzai’s Daitoku-ji lineage. Japanese TV has dedicated an immensely popular anime series to his childhood. Since his mother was dismissed from the court of the emperor Go Komatsu, Ikkyū grew up in relative poverty and was entrusted to a local temple at an early age. However, he is remembered best as the Japanese representative of the “crazy monks” who made a name for themselves by breaking the precepts, more specifically by eating meat, drinking alcohol, and frequenting brothels. Ikkyū, who called himself “crazy cloud” (Jap: kyō‘un) and advocated “crazy Zen” (Jap: kyōzen), is further famous for his rather explicit poetry that leaves little to the imagination and his life-long infatuation with the blind singer Shin. Bernard Faure suggests that Ikkyū was guilty of sexual as well as literary transgressions. However, he was highly critical of corrupt monks and subordinated his transgressions to the bodhisattva vows.*

Ikkyū Sōjun. From terebess.hu

Takuan Sōhō (1573–1645), born in Izushi, was a disciple of Shun’oku Sōen and a confidant to Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604–51). He served the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism as the head priest of Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, starting in 1607, was exiled to Ideba in today’s Yamagata Prefecture in 1629, and became the founder of Tōkai-ji in 1638. A certified Zen master, Takuan gained popular acclaim as the teacher of the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645). His intellectual accomplishment lies in the theory of self-cultivation, as developed in his treatise The Mysterious Records of the Mind of Unmovable Wisdom (Jap: Fudō-chishin-myōroku). In this sword-fighting manual, he applies basic ideas from the Platform Sūtra (Ch: Tanjing; Jap: Dangyō), most prominently, the juxtaposition of the “abiding mind” (Jap: jūshin) and the “no mind” (Jap: mushin) to sketch the process of psychophysical transformation that he believed any practitioner of meditation or martial arts undergoes. Discussing the ideal mindset of a practitioner of sword fighting (Jap: kenjutsu), Takuan lays out his basic metaphysics, ethics, and religious ideology. The text commences by distinguishing between two states of mind: the “delusional mind” (Jap: mōshin) that “abides in a place” (Jap: jūchi) and the “no-mind” that flows freely through the body of the practitioner as well as the body of the opponent. The no-mind, Takuan explains, flows like water and is illustrated by the thousand arms of Kannon Bodhisattva (Ch: Guanyin). Kannon can move her arms simultaneously, since she is not attached to any individual one of them. This means that the ideal mental state, which I have referred to in an earlier essay,** is that of complete detachment. The practice of both Zen meditation and sword fighting is designed to transform the delusion of the everyday mind that is attached to thoughts, emotions, and the objects of the senses, into “no-mind.” “No-mind” is the state, Takuan continues, where “all buddhas” (Jap: shobutsu) and “sentient beings” (Jap: shūjō) are “one” (Jap: funi). Such an attitude of detachment is not only beneficial to combat but constitutes the attainment of buddhahood. Interestingly enough, Takuan adds the suggestion that such a mind also realizes that the three teachings, Buddhism, Shintō, and Confucianism, are originally one. He thus applies the Chinese notion of the “three teachings” (Ch: sanjiao; Jap: sangyō) to the Japanese context.

Takuan Sōhō. From budojapan.com

Takuan Sōhō. From budojapan.comWhat do we learn from these masters? Does it make sense to include them in one short essay besides the value of being introduced to their life and thought? I do think so. If we read the fundamental teaching of these Zen masters in the sequence provided by the alphabetical order, we arrive at the following line of thought: the teaching of Zen is “unborn,” it neither is external to ourselves nor does it lead to new insights, but rather is awakened in our actions. This awakening Hakuin described as the “great death” that is preceded by “great doubt.” In other words, doubt pushes us to a new way of understanding reality. Then, our interaction with the world and with others changes, compassion becomes more important than rules and principles, we see persons as individuals. Thus, we become fluid like water or versatile like Kannon, who is not focused on one arm and one approach but is open to all situations and to all people. This is the teaching of these masters.

* What Use is Morality for Meditation? (Buddhistdoor Global)

** The Metaphorical Sword (Buddhistdoor Global)

References

Favre, Bernhard. 1998. The Red Thread: A Buddhist Approach to Sexuality. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Animals in Priestly Robes in Japanese Art

Rarified, Recondite, and Abstruse: Zeami’s Nine Stages

The Zen of Temples