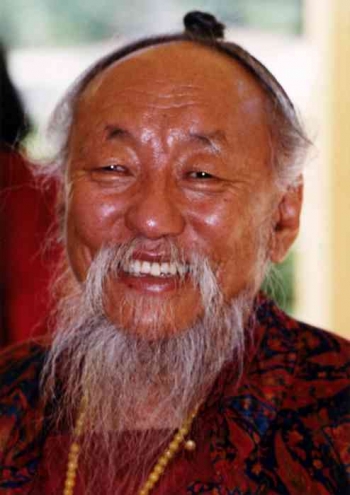

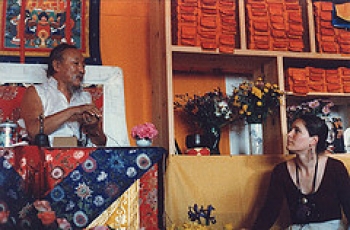

Tsering Everest is the resident lama at Chagdud Gonpa Odsal Ling, a Vajrayana Buddhist center in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Originally from the United States, for 11 years she served as the main interpreter for Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche (1930–2002), a high lama from the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism who arrived in America in 1979 speaking almost no English. Although Lama Tsering does not speak Tibetan and Rinpoche never learned English well, through a past-life connection she was able to understand and “translate” his teachings, “like being able to see the whole painting from just a few strokes.” Immediately following a four-year solitary retreat under Rinpoche’s guidance, in 1995 he ordained her as a lama and asked her to teach in Brazil, which he had visited and where he subsequently established Chagdud Gonpa Khadro Ling and other centers. While Lama Tsering also has many students in the States and travels there each year, she mostly divides her time between her city center and Odsal Ling, a peaceful retreat center on Sao Paulo’s outskirts where she and her husband recently constructed a traditional Tibetan-style temple. This is the first part of an interview in which Frances McDonald talks to Lama Tsering about Vajrayana in the West and the role of tradition.

Frances McDonald: How did the retreat center and temple come about?

Lama Tsering: They came out of an intention to help the people in the region. Even though the city center was thriving, people would not participate on the weekends because most everyone here has a culture of trying to get away on the weekend to recharge. I agree with that, so I talked to Rinpoche and we started looking for a piece of land that was outside of the city but not too far away, where they would have a chance to take it easy and receive teachings and meditate. We first called it “Refugio” because it gave everyone a break, and also meaning taking Refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. So that’s why we ended up with the land, and making the temple there was an extension of that.

FM: What activities take place there?

LT: We have residents at our temple, but as we do have an extended sangha in the region, people come during the week to attend the daily practices. On the weekends our activity is attended by the greater sangha. Those people come for the long version of our Red Tara practice on Saturday, and then on Sunday we use the short practice in Portuguese so that it’s easily accessible and available to new people. Following the practice on Sundays we have an open teaching. Saturdays we usually have work projects going, and the greater sangha comes to do volunteer programs. Beyond this weekly schedule, we also have organized events. And on weekends we have guides who receive the visitors who come to the temple and they give them a little tour. I think the day-to-day functions of the temple are quite lovely, and they support and are enjoyed by many people. We also receive many visiting lamas, particularly Chagdud Khadro, who comes regularly to teach, along with Lama Sherab Drolma, who is a Brazilian lama, and Jigme Tromge Rinpoche also comes at least once a year. In addition, we receive teachings from Dzongsar Khyentse Ripoche, Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche, and other great lamas, including Phakchok Rinpoche.

FM: In most ways Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche was a very traditional teacher, and his students follow a progressive sequence of Vajrayana practices beginning with the sadhana of Red Tara and then moving into the preliminaries (ngöndro) and other deity practices, all the way through to Atiyoga, or Dzogchen. Do the teachers he ordained as lamas have the possibility to change the focus or sequence of the practices if they feel it might benefit the students, or to add in other elements? Do you feel there are any drawbacks to such a traditional approach?

LT: Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche was an amazing teacher, and I had the opportunity to study with him for many years. I would say that he’s a little hard to define. In terms of being a traditional teacher, Rinpoche really seemed to have confidence that we could address the teachings and apply them to our minds. He always trained us in contemplation and questioning and meditating. All along the way, Rinpoche was very kind and thorough in his presentation and in tending to us in order that we could make good use of the practices in our daily life. In terms of the teachings, I try to follow Rinpoche’s way of doing things. I trust it and I believe in it, and I think that I can see over the years the effectiveness of Rinpoche’s way of teaching. He had very delightful examples that were very timeless and applicable, and I enjoyed them very much, but he also allowed me great latitude to use my own examples even during translations of his teachings. As a teacher I do take pleasure in using my examples according to the very traditional teachings that Rinpoche gave, which I really don’t deviate from. Rinpoche was never boring as a teacher. No matter how many times I listened to pure motivation teachings by Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, I never tired of them. They were amazing and fresh and more profound to me each time I heard them, and I think that’s due to the blessings of the lama. As a teacher I refer back always to Rinpoche’s style. I really appreciated it and I don’t think I could do better than that.

FM: In other ways, perhaps Rinpoche could be considered untraditional, in that he ordained a number of women as lamas and was extremely generous with the teachings—his students have a vast array of practices on which to draw. Apparently he didn’t make any distinction between men’s minds and women’s minds, or Asian and Western minds. Could you comment?

LT: I think Rinpoche was kind of visionary in not making those kinds of distinctions. He felt the Dharma needed to come to the West, and even from the United States the Dharma needed to come to South America, which was quite unheard of. Many lamas were coming to the States, but to Brazil? And Rinpoche was elderly. This is an indication of how Rinpoche was about spreading Dharma. He always opened the door, and whoever entered the door he had confidence they were meant to be there, and he gave them everything that he possibly could. He felt that if it wasn’t going to ripen for them in this life, it would certainly ripen in the next, or at a time when it was appropriate for the person listening. I think in a sense Rinpoche was kind of timeless like that.