FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

Visions from the Zen Mind: Zen Paintings and Calligraphy at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

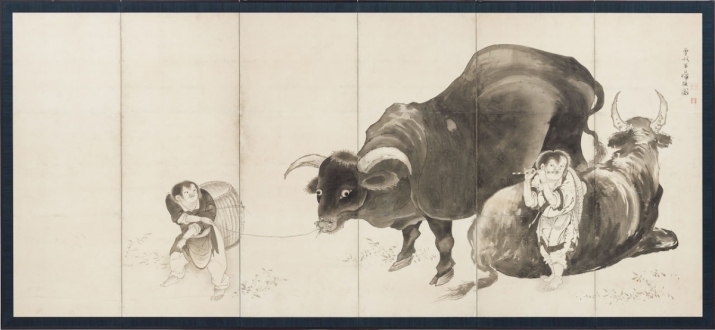

Oxen and Shepherds, by Soga Shohaku (1730–81). Japan, one of a pair of six-panel screens, ink on paper. LACMA, Museum Associates

Oxen and Shepherds, by Soga Shohaku (1730–81). Japan, one of a pair of six-panel screens, ink on paper. LACMA, Museum AssociatesA fuzzy-furred gibbon seated on a rugged boulder reaches an arm out over a rushing river and tries to scoop up the reflection of the full moon in the water. Two impish Chinese fellows wearing ragged clothing, one wielding a broom and the other reading a scroll, interact mischievously with each other and with the calligraphic inscriptions that surround them. The bearded monk Bodhidharma (J. Daruma), wearing a surly expression and red robes, gazes into the distance as if pondering the nature of reality. Close by, processions of black-robed mendicant monks march rhythmically towards and away from the viewer in two slender vertical scrolls, their composition echoing the even more abstract image of a single vertical black line—representing a monk’s staff—plunging sharply downwards as if piercing something of great significance.

Gibbon Reaching for the Reflection of the Moon, by Yogetsu (c. 1485–?). Japan, hanging scroll, ink on paper. LACMA, Far Eastern Art Council Fund (M.83.36)

These images are all visions from the Zen minds of teachers, artists, and acolytes of Japan’s meditational tradition of Buddhism. Created over several centuries by some of the country’s most celebrated Zen painters, the paintings are in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and are currently on view at the museum’s Pavilion for Japanese Art. The exhibition Japanese Painting: From the Zen Mind, which consists of about 30 paintings and calligraphic inscriptions by both professional artists and Zen monks, explores the varied approaches taken by Zen artists to depicting traditional subjects and demonstrates how the attitude and spiritual experience of each artist can produce different qualities in their painting.

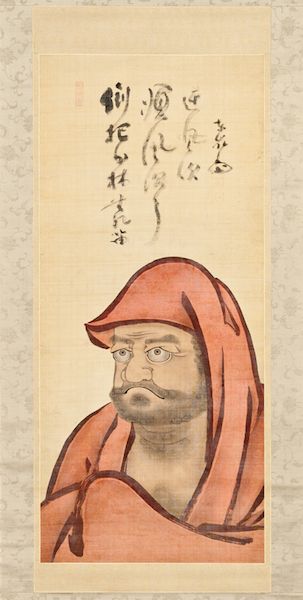

Daruma, by Torei Enji (1721–92). Japan, hanging scroll, ink on silk. LACMA, Gift of the Robert and Helen Kuhn Family Trust (M.2012.106.24)

Zen is a form of Buddhism that rejects practices involving deities and elaborate rituals. Instead, it stresses meditation (Skt. dhyana) as a means of stilling the mind and opening it to truths about reality and existence, and places emphasis on the direct transmission of knowledge from teacher to student—both aspects of Buddhist practice that date back to the time of the Buddha himself, around the 5th century BCE. In the 6th century CE, the Indian monk Bodhidharma is believed to have taken dhyana to China, where it became “Chan” in Chinese. In the late 12th century, at the start of a long period of military rule in Japan, Japanese Buddhist monks traveled to China and studied meditational Buddhism, bringing it back to Japan under the name “Zen.” With it, they also brought powdered tea drinking and current Chinese styles in architecture, poetry, painting, and calligraphy.

Monochrome ink paintings and calligraphic inscriptions, inspired by Chinese examples, became an important part of this direct transmission in Japan’s Zen Buddhist temples. Zen teachers and artists used brush and ink on paper to create abstract, almost philosophical landscapes and images of birds, animals, and comical personages, which were often visual conundrums created to help enlighten the practitioner. In the earlier centuries, Japan’s Zen artists were known more for their painting skills than their level of Buddhist wisdom. Some of the earliest and most breathtaking Zen images are the monochrome landscape paintings rendered with a few deftly brushed outlines and graded ink washes. The rapid brushwork and abbreviation of forms to their bare essence reflect the Zen emphasis on simplicity and spontaneity and a sense of oneness with the natural world. The gibbon by Yogetsu (c. 1485–?) in this exhibition, though not realistic in treatment, nonetheless captures the character of the foolish creature.

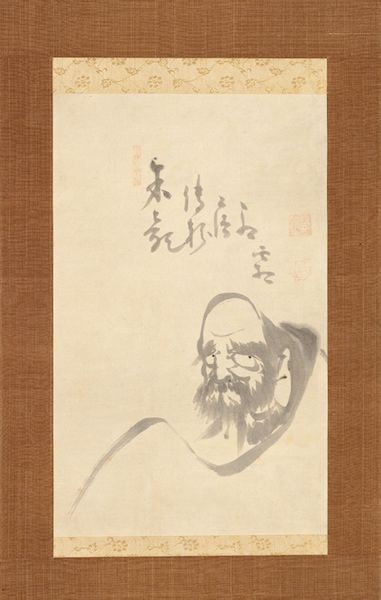

Daruma, by Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768). Japan, hanging scroll, ink on paper. LACMA, Gift of the Robert and Helen Kuhn Family Trust (M.2012.106.9)

By the 17th century, however, the tide had turned, according to LACMA’s curator of Japanese art Hollis Goodall, who curated the present exhibition. “Around this time,” she explains, “Japan’s Zen masters began painting and using calligraphic techniques as a means of creating understandable lessons for acolytes and lay practitioners.” Although they did not always possess the extensive training of many of the earlier Zen artists, these Zen masters nevertheless followed in the footsteps of early Chan and Zen painters, creating monochrome paintings that favor abstraction over realism and that capture the essence of their subjects with a few skillfully executed strokes. “Japan’s later Zen painting,” adds Goodall, “is sometimes wild and humorous and is filled with the insight and the energy of the masters.”

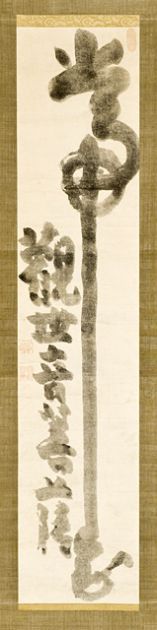

Kannon; Always, pray to the Bodhisattva Kannon, by Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768). Japan, hanging scroll, ink on paper. LACMA, Gift of the Robert and Helen Kuhn Family Trust (M.2012.106.10)

Probably the most revered of these later Zen masters is Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768), a monk credited with revitalizing the Rinzai school of Zen in the Edo period (1603–1868) and dedicated to bringing Zen wisdom to all. Hakuin believed in the importance of continuous, rigorous spiritual training in order to deepen the insight of enlightenment and to manifest it in daily life. Also a talented artist, he used calligraphy and painting later in his life to convey lessons to monks and serious practitioners and also to spread Zen teachings among the wider lay community. His paintings display vivacious brushwork that shows the strong influence of calligraphy. His calligraphy is no less impressive, and can be seen in this exhibition in a slender hanging scroll bearing the inscription “Kannon; Always, pray to the Bodhisattva Kannon.” The two characters in the name “Kannon” (Skt. Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion) are stretched out vertically to resemble a monk’s staff (the subject of another of his works in this exhibition), perhaps an allusion to the power of this deity to provide strength and support to followers and also a generous salute to Buddhist practice outside the traditional Zen arena. Hakuin also painted countless images of Daruma, often abbreviating the images to a bust portrait with a three-quarter view of the monk’s head and shoulders. He gave his Daruma figures big, round eyes with a tiny pupil at the top of the eyeball, and the monk’s body is simply suggested by a single, bold curving brushstroke that denotes the edge of his robe.

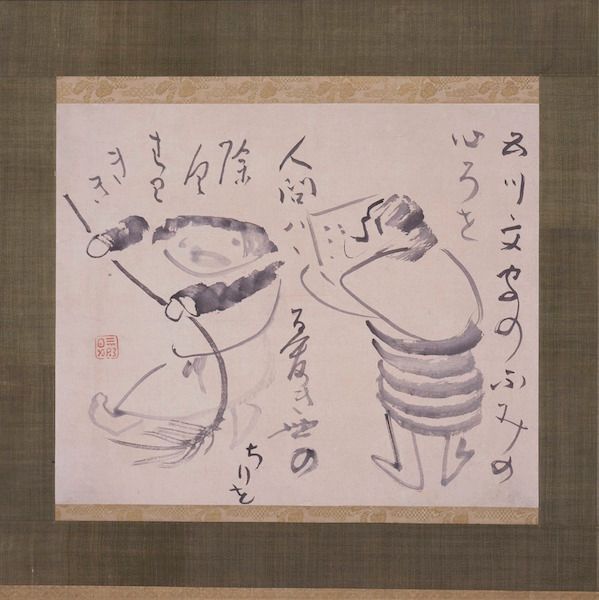

Kanzan and Jittoku, by Sengai Gibon (1750–1837). Japan, hanging scroll, ink on paper. LACMA, Gift of Murray Smith (AC1999.253.2)

Also represented in this exhibition is Sengai Gibon (1750–1837), a Zen master and artist known for his controversial teachings and writings as well as his light-hearted Zen painting style. Famously depicting the Buddha as a frog and abstracting Buddhist teachings into geometric forms, he demonstrates through his witty and whimsical paintings how humor can be used to teach profound truths about reality. In this exhibition, we see two very different portrayals by this artist of the poet Hanshan and his simpleton sidekick Shide (J. Kanzan and Jittoku), two Chinese eccentrics celebrated in Zen painting for their simplicity and spontaneous merriment. In one painting he presents the two figures together, Kanzan reading from a scroll and Jittoku sweeping comically with a flimsy broom. His playful, almost childlike brushstrokes for the figures and the surrounding calligraphic inscription reflect his free artistic spirit and populist approach to Zen teaching, which he believed should be made understandable to all, including ordinary townsfolk and farmers.

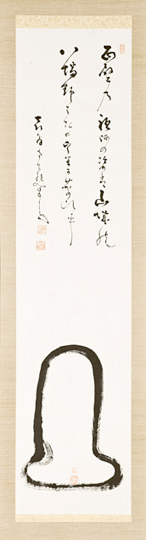

Daruma Facing a Cave Wall while Meditating, by Nakahara Nantenbo (1839–1925). Japan, 1916, hanging scroll, ink on paper. LACMA, Gift of Murray Smith in honor of the museum’s 25th anniversary (M.2004.282.1)

Following in the footsteps of great Edo-period artists like Hakuin and Sengai, the Zen master Nakahara Nantenbo (1839–1925) also expressed his Zen Buddhist beliefs through painting and calligraphy. Known for his strict discipline, which often included beatings with his Nandina wood staff (J. nantenbo), he created most of his paintings and calligraphy when in his late seventies and early eighties as part of his daily religious practice. His portrayal of Daruma in this exhibition represents the meditating monk with a single stroke. Though his figure resembles a pear more than a man, the strength of his brushwork and his conviction in the truth of the Zen teachings helps us see a monk who is so devoted to his meditation practice that, as he sits for hours facing a wall, he has perhaps transcended his human self.

Although most of these paintings were created as part of a monk-artist’s daily Zen Buddhist practice or as tools by teachers who hoped to transmit Zen teachings to their disciples, the works hold broad appeal beyond the context of Zen Buddhist temples. Goodall credits the interchange of ideas between abstract expressionist gestural painters and Zen monks brushing calligraphy or Zen subjects with making Zen painting easier to understand in the West. “However,” she adds, “those who have taken a deeper interest in Zen painting often enjoy it for its multiple layers of cultural and spiritual meaning.” Museum-goers in the Los Angeles area are fortunate to have access to the works and thus the minds of these Japanese Zen masters, who conveyed so much through so few strokes of a bamboo brush.