FEATURES|THEMES|Environment and Wildlife

Visions of Spiritual Ecology: Diane Barker’s Photography of Tibetan Nomadic Life in China

Sonam Wangbo and his friend Dawa in pastures filled with edelweiss. We were on our way up to the family’s summer camp in high alpine pastures. Dahu Valley, Kham, 2017. Photo by Diane Barker

Sonam Wangbo and his friend Dawa in pastures filled with edelweiss. We were on our way up to the family’s summer camp in high alpine pastures. Dahu Valley, Kham, 2017. Photo by Diane BarkerFew outsiders to the Tibet-Qinghai Plateau have had the same access as Diane Barker, a painter-turned-photographer who has moved in diverse circles across Asia since the 1990s. At present, her photographic focus is on the drokpa, which translates roughly to “people of the solitudes.” These nomadic communities embody the oldest traditions of life in this remote region: patterns of herding, horsemanship, and kinship bonds that date well into the earliest periods of Tibetan history. The great irony, as she puts it herself, is that although she has a deep bond with the drokpa, camping and being in the cold are not things she enjoys (and in Tibet, the nights are extremely cold). “I’m not a great hiker in outlandish places either,” she says. “I’m more of an ambler through gentle British countryside. I do really enjoy riding Tibetan horses though. Anyway, love chooses you, not the other way round, and for me my fascination with the drokpa is a love affair.”

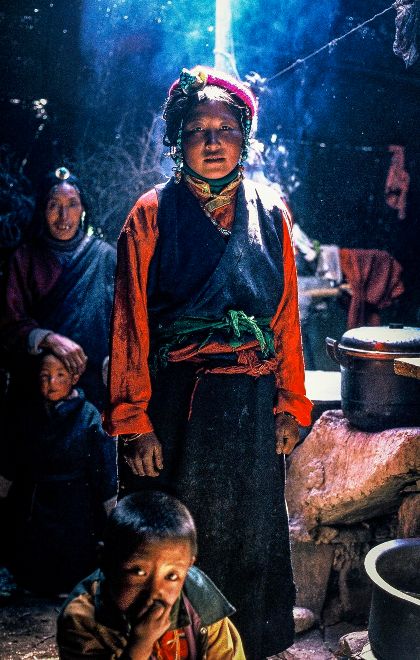

Woman in a pool of light. Sersong's daughter in the family tent.

Taelung area, Kham, 2000. Photo by Diane Barker

Diane’s interest in photography began at an early age. Her mother was instrumental in facilitating this passion, buying her first camera at 12 and giving her books about great photographers such as Bill Brandt and Henri Cartier Bresson. Some years later, her father’s friend, learning that she was studying the history of art at university, gave her two boxes of books on art. “Nearly all of them were about great American photographers, like Dorothea Lange and Edward Steichen. I began to take photography seriously as a way to record and express life, and I would spend nights in the darkroom of the university, printing black and white photos.”

Bashful nomad cowboys came to town, strutting their macho stuff until I pursued them with a camera and then they came over all shy. Dechen, Kham, 2000. Photo by Diane Barker

Bashful nomad cowboys came to town, strutting their macho stuff until I pursued them with a camera and then they came over all shy. Dechen, Kham, 2000. Photo by Diane BarkerLater, Diane would find her spiritual teacher in the mystic tradition of Sufism. Nevertheless, since 1978 she has maintained a strong connection with Vajrayana Buddhism, and by 1994 she acted on her fascination with Tibetan culture and began taking photos of different Tibetan communities in India. “I have always had a feeling for indigenous, earth-based cultures. When I was very young, I read the comic strip life story of Chief Crazy Horse of the Lakota and fell in love. I was entranced by his story and the portrayal of his beautiful earth-based lifestyle. In the 1970s, I traveled in America. Visiting the museum in Phoenix, Arizona, I was deeply moved by their collection of First Nation artifacts. There were exquisite fetishes, pots, clothes, baskets, jewelry, and more, all lovingly created from available natural materials. I was very inspired. Then almost immediately I felt a tremendous sadness at how all this was, as I perceived it then, lost. Where had this astonishing culture gone?”

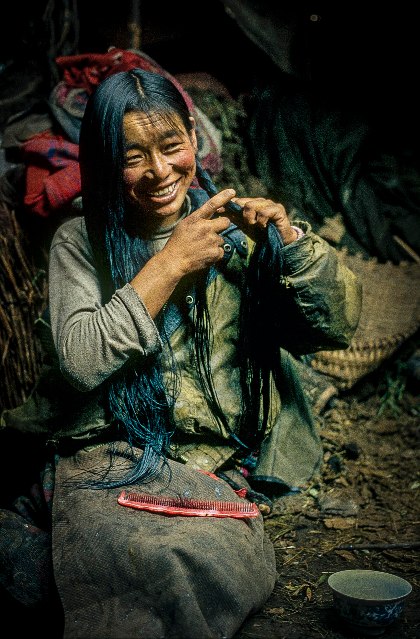

Tashi braiding her hair. South Amdo grasslands, 2000.

Photo by Diane Barker

Years later, Diane was commissioned by a publisher in New Delhi to take photos of nomads in Ladakh: “They gave me a deadline of only three weeks without giving me any contacts or directions on how to find them. Consequently the deadline came and went and I still had not come across any nomads, but my search turned into an obsession. Finally, I found four young men who reluctantly agreed to take me to the Changthang desert where they were headed.”

As it turned out, she found her nomads within a day. “We drove off the road into the desert and eventually crested a rise and came down to a salt lake, where there was a small white picnic tent with horses nearby. Out of it emerged these glorious wild and earthy men with long hair, earrings, and homespun clothes and felt boots—and I was smitten. I realized that here was a beautiful earth-based indigenous culture that was still alive and intact. I was deeply struck by how there seemed to be no separation between them and their environment—there was an extraordinary sense of oneness that I had never encountered before.”

Palmo returns from milking on a frosty July morning in summer pastures in Ramashong Valley, Kham, 2015. Photo by Diane Barker

Palmo returns from milking on a frosty July morning in summer pastures in Ramashong Valley, Kham, 2015. Photo by Diane BarkerWhile she felt the grand, primal resonance in her encounter with the nomads, one experience that she remembers particularly vividly—and, through her current work, enjoys returning to whenever she can—is the warmth and openness of the Tibetan families.

“When my friend Hilary and I first set out on horseback for a nomad camp in Amdo, I remember that it was raining and cold, and yet, as we climbed up into the grasslands, I felt as if I’d waited my whole life for this moment and I couldn’t have been happier. I remember the sound of horse bells as we rode for a day and a half and the excitement I felt on the second day, when we finally saw the black tents of the drokpa in the distance. Even though I was longing to take a look inside, our host, Choegyal, led us past the many black tents of the community spread over a large area before we finally arrived at his home, on a ridge overlooking a valley. As we entered his tent I was overcome by the welcoming warmth and dryness inside and the pervasive smell of tsampa (their staple food), butter, and smoke. That night Hilary and I set up our own small tents, and I soon realised that mine was totally inadequate for high plateau camping, and I longed to be in the warmth of a black yak wool tent. Despite my Western fleece and windproof and waterproof layers, I was cold and miserable until our very tolerant hosts lent me a heavy yak wool blanket to sleep under.”

She describes the fortnight she spent in this camp as a magical one. “I fondly remember all the times Choegyal’s wife Tashi and I, with no common language, would mime earthy jokes about yaks’ flatulence and end up rolling about with laughter. Choegyal had been given a solar-powered ghetto blaster and I had a mixtape of songs, which he played on it, and I remember him dancing round the tent to his favourite track, Fisherman’s Blues, by the Irish folk band the Waterboys. In fact, years later I met Mike Scott of the Waterboys at an event in London and shared the story with him.”

Image courtesy Diane Barker

Image courtesy Diane BarkerIt is impossible for industrialized economies to return to an indigenous way of living. Our transition into a highly technologized world is inevitable. Nevertheless, Diane has come to appreciate how the nomads’ stewardship of the land, which she describes as gentle, self-sustaining, and organic, is very pertinent today and can teach us important things amid the global climate crisis. “They live their life in harmony with the seasons and are mindful of the health of their animals and that of the high-altitude grasslands. In fact, environmental scientists now realize that yaks ensure the biodiversity of the grasslands. Nomads have always been very careful not to harm their environment. Anything they no longer needed was easily biodegradable—clay stoves, for example, were left behind to disintegrate back into the earth when they moved on. Their footprint was very light,” she notes.

“Tibetan nomads are not driven by market forces, consumerism, and greed, but instead live their simple lifestyle in preference to a settled urban one. Traditionally yaks (and often sheep and goats) provided the drokpa with most of their needs: food, wool for clothes and their tents, hides for bags, dried yak dung as fuel for their stoves, and so on. For other needs, such as barley for tsampa, Tibetan nomads would operate as a small co-operative, to barter with farmers in the valleys.”

The guys. Ani Tenzin Yangchen’s winter home, Rakchennang Valley, Nangchen, Kham, 2018.

Photo by Diane Barker

“The Tibetan belief that the land is sacred, animated by earth-protector spirits (that they should respect and not offend), demonstrates their sensitivity to and protection of their environment. Unfortunately, we in the industrialized world have long lost the belief that our earth is sacred. We exploit and plunder it as if it’s an infinite resource, but if we learned from the nomads, and Tibetans in general, we would think carefully about everything we do in relation to our mother the Earth. We have forgotten that we are one with her. Sadly, separation seems to dominate our global consciousness in these times and, if we do not heed the warnings of our Earth—floods, wildfires, melting glaciers, loss of species—it could lead to our extinction.”

For now, her photographic style and interests seem to reflect the mentality of the nomads she has come to count as among her close friends: instinctive, intuitive, and non-analytic. “When I photograph people I fall in love with them and I hope that my passion for the drokpa’s dignity, uncomplicated nature and inner stillness is reflected in my photos.” The very definition of Tibetan nomadic life is that they are surrounded by the grandeur and vastness of nature. There is nothing else to impinge on their lives, and her photos reflect their connection with that land.

See more

Diane Barker

My Best Day - Diane Barker, Victims' commissioner Claire Waxman, Playwright Tanika Gupta (BBC Women’s Hour)

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Green Himalayas: Ladakh Launches Ambitious Climate Change Project

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Jacques Bacot’s Rebel Tibet, Part One: Early 20th Century Travels to Kham

Jacques Bacot’s Rebel Tibet, Part Two: From the Great Temples to Early Modern Tibetology

Jacques Bacot’s Rebel Tibet, Part Three: Buddhism in Interwar and Postwar France

Tibet on the Silk Road from a Curator’s Eye: An Exhibition Tour with Dr. David Pritzker

Candid Amdo