Some equate being British with the most barbaric oppressors in history, which they have been. Today it could be Lord and Lady Waxed Mac and Wellie Boots, others might be Mr. and Ms. Cheeto Tan, and Barbie Hair, who are motivated only to scroll their iPhone and maybe access deeper parts of the nasal cavity with nails so long they come dangerously close to the brain. Is being British about Pimm’s and lemonade and summer dresses? Is it those for whom the hair on their head has migrated south, like their low-hanging trousers? Or perhaps it’s those whose use of “Shakespeare’s language” has followed the migration of the aforementioned hair. Maybe it’s the libido-driven rugby lads? Or those who like to drink tea and say sorry—a lot? Or, just possibly, it’s the millions simply trying their damndest to get by in life? To which Brit are you referring? One of the above? Or one of the numerous communities who have crossed the waters to these shores? Asians? Africans? Eastern Europeans? Spanish? French? Maybe the Normans? Scandinavian Vikings? Goodness knows people love laying claim to that ancestry! Germanic Anglo-Saxon? Italian Roman? A Neanderthal who made her way to this landmass more than 40,000 years ago?

FEATURES|COLUMNS|Silk Alchemy

When Worlds Collide, Can I Say Namaste?

Photo by Kirill Palii

Small worlds have always collided. Societies swallow other societies, or at the very least mix bodily fluids until you’re not quite sure where one begins and ends, while the other lies there wondering what just happened, or if that was it.

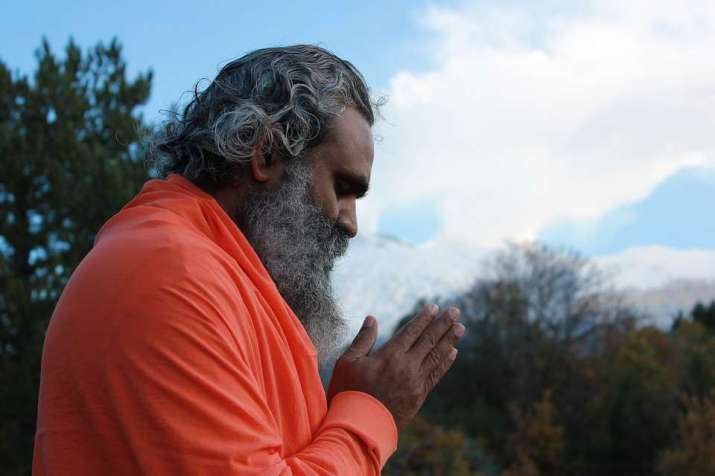

I recently watched a live-feed on social media by someone I know personally—a lovely woman who is doing good things in the world. She was signing off and started to say “namaste” when she cut herself short and shared that someone had reprimanded her for using the salutation, citing cultural appropriation. I was sad and cross. No similar term exists in English in quite the same way, but the sentiment is felt and shared by many. It is the sentiment embodied in the term namaste, and that sentiment has no boundaries.

Of course, we should not cherry-pick from a culture in ways that bastardize it to meet our personal criteria. Nor should we nurture a culture of oppressors who then romanticize the oppressed culture as something almost magical that we want to claim as our own. However, nationalism is as ridiculous as birds claiming a cloud. Please, hear me out!

We humans are a migratory species. Even if some of us are happier with our own little nest, the idea that we determine our identity by the cloud we’ve chosen to call home does seem a little daft in the larger context. By way of illustration, I might ask who are they if “they” are British?

From wikipedia.org

From wikipedia.orgHow far back do these strange conceptions of nationalism need to travel—850,000 years, give or take, to when the first of four differing hominids meandered to the northwest of the landmass before it became separated by water amid dramatic climate change?* Cheddar Man, who gave us exceptional DNA from approximately 10,000 years ago, came from a migratory people who had traveled from the Middle East. They settled here and the British population of today carries around 10 per cent of that DNA. And in all this, I am only speaking of the socially accepted dates, rather than those which contravene our accepted timeline narrative.** (But that’s a rabbit hole for another occasion.)

Culture, on the other hand, is a different matter. We make that. Although we, as a species, haven’t changed much over the millennia, we like to think we have. But we still spin out the same old stories lifetime over lifetime, like a scratched old record. We’ve simply morphed the landscape around us, metaphorically as well as physically. Today we have technology and consider ourselves very clever. The ancients had swords and also considered themselves very clever.

The objectives seem to be the same, however: acquisition. The motivation to acquire is often rooted in an inadequacy, be it a feeling or a sense of desperation that may be beyond one's control. For example, drought leads to crops failing and people starving. And this creates a very natural desperation to acquire food. Today, a lack of funds threatens in a similar way to crop failure. This can lead some to push themselves in work to reap those rewards, while someone else may take to crime. Inadequacy can lead people to desperate and irrational responses. When feeling emotionally inadequate, acquisition takes on a different energy. At one extreme, the oppressed may become the oppressor, or the ignored teenager may be driven to become a starlet.

Namaste

NamasteAcquisitiveness can take many forms. At its best, it is a drive to acquire wisdom and abilities beyond our current level. At its worst? Well, let us simply say that very few cultures seem to have managed acquisition in ways that have improved on the crassness of just punching someone and taking what they want. Historically, however, it would appear that a few—very few—have engaged in what we could call a non-zero-sum game; a win-win for all concerned. According to archaeological finds, some cultures seem to have used their time to live together, to create, to embrace their creativity and use it for trade. This type of culture could grow rather than grieve. It is also curious to me that these societies seem to have been either egalitarian or matriarchal.*** I do wonder about the implications of this when thinking about the aforesaid “inadequacy” of sword-driven acquisition among other cultures.

Landscapes will morph people who settle, of course, and this creates routines and behaviors typically based on survival—the when and how of food acquisition being one of the most fundamental. These routines become events that create historical experiences for the communities involved, forming cultural identities.

Then cultures clash, like children forming territorial gangs in a playground.

I am simplifying, of course, but my point is that, as a species, we are missing the point. For starters, “culture is not your friend,” as the late American ethnobotanist and mystic Terence Mckenna said during his 1998 “Valley of Novelty” series of lectures:

Culture is for other peoples’ convenience and the convenience of various institutions, churches, companies, tax collection schemes, what have you. It is not your friend. It insults you. It disempowers you. It uses and abuses you. None of us are well-treated by culture.

And so it behooves us not to buy into this constructed existence. Instead, we must rise above it. Recall the astronauts who looked back on this small, shimmering lapis-emerald globe hanging in the vastness of space. Recall our higher consciousness that incarnates to experience itself. Global happenings are a mess. We cause unimaginable pain and abject suffering for fleeting satisfaction, and it’s deplorable and pathetic. It’s time we recognized the playground for what it is and relearned how to play with each other—nicely. Aim for that non-zero-sum game again.

Photo by Ivan Samkov

* Thanks to fossil finds and DNA analysis, four distinct hominin have been identified in the British Isles. Antecessor, heidelbergensis, neanderthalensis, and sapiens. Ref: Josie Mills “Migration Event: When did the first humans arrive in Britain?” 24 February 2019

** A controversial subject. There are archaeological finds that date hominin closely associated with modern man as significantly older than the given timeline. Bones, as well as tools, have been found in bedrock and coal dating back well over a million years. In some cases, significantly over 10 million years. There are many well-researched talks and papers out there. Dr. Michael Cremo is one of many worth a read to research this fascinating subject. If it is indeed the case that the humanoid species is millions of years older than we’re told, it raises questions pertaining to ancient religious myths, and to why governing bodies are so adamant about not holding open discussions.

*** Archaeological finds such as in the Indus Valley, Çatalhöyük, pre-dynastic Egypt, and earlier, where communities of people simply got on with living. To do this, each simply did what they could, regardless of gender. We must be so careful not to surmise their lives; today, opinions still reflect on ancient people as if being a woman with equal standing or even leadership was anomalous to human nature. All behaviour and art was for ritual. These assumptions have often been filtered through a very biased mindset.

See more

Tilly Campbell-Allen (Dakini as Art)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

God of the Unknown: The Buddha in Chilean Magazines at the Turn of the 20th Century

Connecting the Past and Present of Shugendo – The Revival of Japan’s Ancient Mountain Ascetic Tradition, Part Five

From Bias to Balance: Liberating the Roots of Perception