Born in a comfortable Parisian suburb in 1868, the only daughter of an elderly couple, young Alexandra quickly developed an independent mind. She is said to have run away from home at the age of two, the prelude to a long life of travel and discovery. As a teenager, she became deeply interested in religion. While still writing personal notes and prayers to God and considering Jesus her “master,” she soon rejected Catholicism—like many French intellectuals of her time, she considered Christianity a patriarchal, oppressive, superstitious religion, the morals of which she believed were contrived only to suppress people’s real needs and desires. Seeking an alternative path, she read extensively about Greek philosophy (especially Stoicism), ancient Greek and Egyptian cults, Kabbalah, Islam, and Western esotericism. At the age of 20, she became a Freemason like her father and frequented other esoteric groups, including the Theosophical Society, which played a key role in her discovery of the spiritual traditions of Asia.

FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

Who was Alexandra David-Neel? A Brief Story of a Buddhist Anarchist

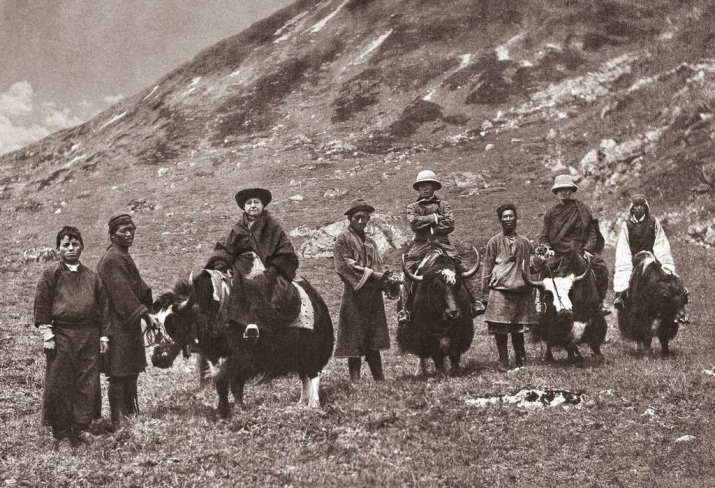

Alexandra David-Neel in Tibet. From oldcivilizations.wordpress.com

Alexandra David-Neel in Tibet. From oldcivilizations.wordpress.comAlexandra David-Neel (1868–1969), a French traveler and a prolific writer, is variously celebrated for being “the first Buddhist in France,” “a fearless explorer,” “the first Western woman to reach Lhasa,” “a mystic,” “a great sage,” “a bridge between Tibet and the West,” and “a White lama.” Although not entirely untrue, many of those appellations tend toward the mythological rather than the historical and it is therefore worthwhile to ask the question, in what sense was David-Neel a Buddhist?

Alexandra as a teenager, 1886. From wikipedia.org

Alexandra as a teenager, 1886. From wikipedia.orgDuring this period she also deepened her knowledge of Buddhism in the few Parisian places where it was being discovered: the Guimet Museum, the Sorbonne, and the Collège de France. It is often mentioned in accounts of her life that David-Neel later converted in front of an imposing Buddha statue at the Guimet Museum and remained a committed Buddhist until her death 80 years later in 1969. Some observers—including David-Neel herself, half jokingly—interpret her conversion to Buddhism and subsequent travels to Asia as an indication that she had lived in Asia in an earlier lifetime. As it is often said in the “Fortress of Meditation,” a small estate in Provence that was her last home and became a museum and the headquarters of the David-Neel Foundation, “Alexandra understood Eastern philosophies with a yellow soul.” Although a Westerner, born into a European society, David-Neel was described as having an Asian mind, to explain why she left the country of her birth and was able to live so easily, for so many years, among Buddhists, Hindus, Shintoists, and Taoists.

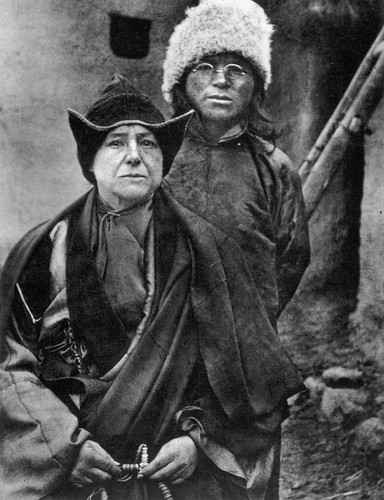

David-Neel with her traveling companion Lama Aphur

Yongden, whom she met in 1914. From

duerkennstmichnicht.wordpress.com

Historians of religion, however, can seek to understand David-Neel’s passion for Asia and for Buddhism from a more empirical perspective—highlighting her intellectual formation and examining her social activities in the specific context of her time and place: the Parisian bourgeoisie of the late 19th century, then fascinated by all things “Oriental” and prey to intense religious uncertainty. When David-Neel discovered Buddhism in the late 1880s, she was a social rebel—a disciple of the renowned geographer, journalist, anarchist, and pedagogue Elisée Reclus, and a member of various radical and feminist groups. Reclus introduced her to other anarchist thinkers, such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Mikhail Bakunin, and Max Stirner. Like most leftist ideologies, anarchism derives from the French Enlightenment: it is atheistic, materialistic, individualistic, and wishes to overthrow the established order, considered oppressive and authoritarian by its very nature. Instead, proponents of anarchism aim to establish a non-hierarchical society, within which each individual can act freely, without contradiction by any state, law, custom, moral, or religion. She adopted this worldview while in her twenties and Marie-Madeleine Peyronnet, David-Neel’s personal secretary for the last 10 years of her life, notes that she remained a convinced anarchist until her death.

It is within this particular context that David-Neel identified as a Buddhist. She expressed a desire to live an “intense and integral life,” untied from the expectations of other people. At that time, women were expected to either become a wife and mother or to seek employment in industry, trade, or agriculture. It was rare for women to attain an intellectual position in society—which David-Neel longed for. Female writers and artists were generally unpaid for their work. Only actresses, who were becoming both popular and controversial during La Belle Époque (a period of peace, prosperity, and optimism in Western Europe in the years leading up to the First World War), were professional artists.

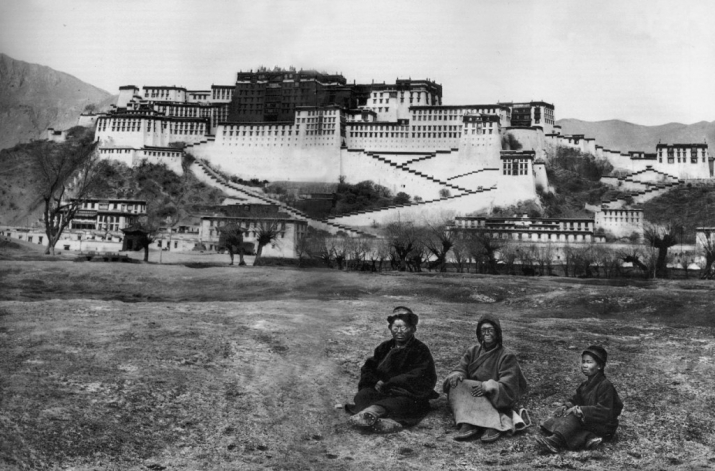

David-Neel, Lama Yongden, and a young Tibetan pose in front of the Potala Palace, Lhasa, in 1924. from iter.org

David-Neel, Lama Yongden, and a young Tibetan pose in front of the Potala Palace, Lhasa, in 1924. from iter.orgIn later years, she would surprise everyone when, at the age of 36, she married Philippe Neel, a successful and handsome engineer based in Tunis. However, her decision makes sense in the light of her individualistic philosophy: David-Neel left her husband a week after their wedding, beginning her 14-year journey through Europe and Asia, during which he sent his wife money and collected the letters and objects she sent from distant lands. The marriage offered her the financial security and social respectability she needed, sparing her from the material and intellectual mediocrity of the impoverished spinster.

In the late 1880s, long before her great journey throughout Asia (1911–1925), David-Neel deepened her knowledge of Buddhism at the Guimet Museum, where she contemplated magnificent statues from Asia and eagerly consumed scholarly works—the most important of which was probably Introduction au bouddhisme indien (1844) by Eugène Burnouf, the renowned philologist who identified Buddhism as an original Indian tradition. David-Neel was then working as an independent journalist for socialist and feminist newspapers, in which her militant articles introduced Asian figures and philosophies—still dealing with the same anarchical obsession: the defense of the individual against society.

Her first writings on Asian thought were thus primarily an extension of her political activism, at least at the beginning. She first wrote about “Meh-ti” (Mozi) and “Yang-Chu” (Yang Zhu), two relatively obscure 5th century BCE Chinese philosophers. David-Neel viewed Mozi’s philosophy as an early Asian expression of socialism, whereas she deemed Yang Zhu a champion of individualism, and through these two early examples, she sought to claim an ancient legitimacy for political and philosophical radicalism. She celebrated Yang Zhu’s worldview, which consisted of an anarchical and materialistic amorality: there is no God to dictate one’s behavior, there is probably no soul and therefore no life after death, all laws enacted by humans are false; each individual is a transitory combination of cells, and therefore one should only follow one’s instinct to survive and avoid suffering. One should not try to be compassionate, virtuous, or altruistic, for those feelings are hypocritical and unnatural. In the words of Yang Zhu: “If by sacrificing one of your hairs you could be beneficial to the entire universe, do not make that sacrifice. Just follow nature and everything will be fine.”

David-Neel’s interest in the Buddha emerged from the same kind of social concerns: here was another Asian thinker who announced the end of hierarchies, the inconsistence of the self, the illusion of the gods. The Buddha, she felt, was a radical who refused to answer any metaphysical questions, only offering his disciples, as she wrote in Le Modernisme bouddhiste et le bouddhisme du Bouddha (1911), “a simple program, the plan for an intellectual fight that man alone has to carry out, and of which he must triumphantly emerge by his own means.” David-Neel described Buddhism as the opposite of religion. Deprived, as she believed it to be, of any ritualistic, devotional, or social dimension, she viewed Buddhism as a down-to-earth, individualistic philosophy aimed at helping people realize the dreamlike nature of the world: “Siddharta Gautama is a master, only a master: he proclaims the facts that appeared to him in his investigations, his meditations, and indicates the means through which we can ‘awake,’ to deliver ourselves, as he delivered himself, from the dream populated by phantasmagoria in which ignorance keeps us.”

The “Fortress of Meditation,” David-Neel's last home, which has become a museum and the headquarters of the David-Neel Foundation. Image courtesy of the author

The “Fortress of Meditation,” David-Neel's last home, which has become a museum and the headquarters of the David-Neel Foundation. Image courtesy of the authorDavid-Neel became increasingly interested in Buddhism because of all the ancient doctrines from which she drew inspiration for her life, it was the only one that was still alive and practiced. The end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries was a time when ethnography and reportage were becoming highly popular. Studying living Buddhism thus became a natural ambition for an adventurous lady who wished to pursue the “man’s” profession of an “Orientalist”: she would go on to visit Asia to collect information about the “rational philosophy” she discovered in Burnouf’s books. The astonishment she later experienced in the field and the way she made sense of what she called “the sort of Catholicism over which the yellow Pope presides,” is another story. Suffice it to say, for now, that David-Neel did quite a good job as a self-trained ethnographer, but she never, as her secretary testified, practiced any kind of ritual or sitting meditation when she returned home. “That’s because Buddhism is not a religion”, Mademoiselle Peyronnet told me, “but a philosophy for the intellectuals.”

Marion Dapsance, a Robert N. Ho Family Foundation/ACLS postdoctoral fellow, received a PhD in Anthropology from the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (Sorbonne), Paris (also attended by Alexandra David-Neel!) and published her dissertation on Sogyal Rinpoche’s sangha (Les dévots du bouddhisme, Paris, Max Milo, 2016). Currently in residence at Columbia University’s Department of Religion, she is working on an intellectual biography of Alexandra David-Neel. She can be contacted at mdapsance@gmail.com.