Wholehearted: Slow Down, Help Out, Wake Up – Living a Life of Vulnerability and Compassion with Zen Buddhist Teacher Koshin Paley Ellison

By Nina Müller

Buddhistdoor Global

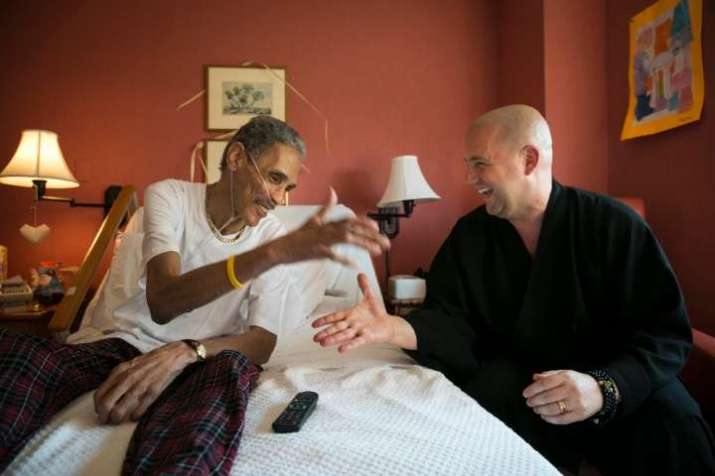

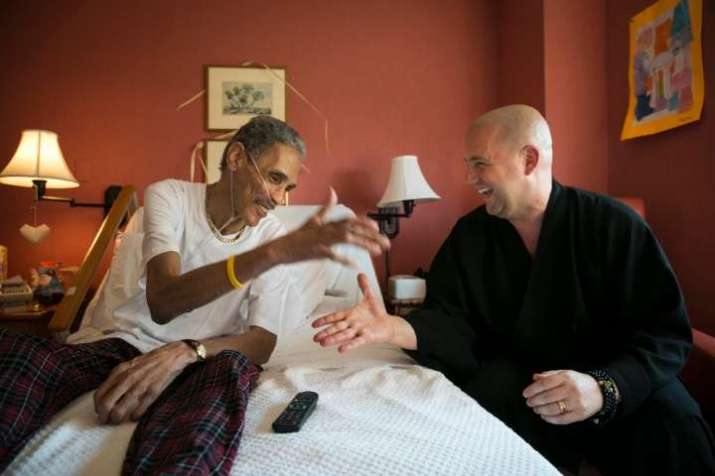

| 2019-09-09 |  Zen teacher Sensei Koshin Paley Ellison, right. Image courtesy of Koshin Paley Ellison

Zen teacher Sensei Koshin Paley Ellison, right. Image courtesy of Koshin Paley EllisonSensei Koshin Paley Ellison is a Zen teacher, psychotherapist, and author of Wholehearted: Slow Down, Help Out, Wake Up (Wisdom Publications 2019). Together with his husband Sensei Robert Chodo Campbell, he cofounded the New York Zen Center for Contemplative Care (NYZCCC), a nonprofit organization in the Soto Zen lineage of the White Plum Asanga in Chelsea, New York. Unlike the average Buddhist center in North America, NYZCCC offers people the opportunity to learn how to integrate their practice into their daily lives and livelihoods. Very much in line with the Japanese practice of attaching societal institutions to Buddhist monasteries, NYZCCC has both a Zen center and a school where people can learn how to care for others—an idea that was the vision-child of Koshin’s grandmother.

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley Ellison

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley EllisonKoshin explains that he was exposed to Buddhism from an early age. Some of his family members had lived in Japan and his childhood home was full of Japanese art, such as Woodblock prints. “I was always very drawn to the imagery and it seemed like it was pointing to something very elemental in my own self,” he explains.

In Wholehearted Koshin describes being struck by the picture in a magazine of a Zen monk standing still and in focus in the backdrop of a crowded Tokyo scene. He knew there and then that, when he grew up, he wanted to be like that Zen monk.

Among other things, Koshin was impressed by the monk’s “amazing capacity for stillness in the midst of chaos.” He shares that the image may have been so striking to him because he had a very tumultuous childhood. In his book, he writes that his family members were deeply affected by the Holocaust, and their traumas manifested in the perpetuation of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. He also explains that being a gay person made him a target of bullying, and when his family moved to a poor, rural town in the Adirondacks in upstate New York, they were persistently harassed and attacked for being Jewish. From a very young age, Koshin learned that “danger can be everywhere.”

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley Ellison

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley EllisonI ask him how these experiences have impacted his role as a teacher and psychotherapist. He tells me that he knew and knows suffering, not in an abstract way but in very literal manifestations of physical, mental, and spiritual suffering. He knows too well the struggle of pivoting from the Third Noble Truth to the Fourth Noble Truth, to the path. “I feel like I bring that to all the work that I do with students and physicians and I’m able to (maybe) have deep compassion, because I’ve had to cultivate that for my own experience. . . . There’s a bit of my own sense of realness that is really helpful. And I can be curious about their suffering because I really have spent so much time investigating mine. And each of us has our own unique path.’’

Wholehearted is both deeply insightful and funny, but overall it struck me as incredibly personal. It is unique for the simple fact that it incorporates important elements of Koshin’s lived experience: from his Buddhist practice and his studies in psychotherapy and poetry, to his interest in fairytales, astronomy, and mythology. “One of the things that I love about Buddhism is that it always adapts to where it is. And right now, I feel like we’re living in a time where we have so much wisdom from many directions: from science, from psychology, and from fairytales from our culture. And the beauty of Buddhism as it has moved from country to country is that it adapts and integrates into where it is.”

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley Ellison

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley EllisonKoshin hopes that readers will reflect on how the topic of each chapter—which in total cover the 16 precepts of Zen Buddhism and can be read in any order desired—may be applied to their own lives. In my view, the book is very successful in doing this, particularly because each chapter ends with a couple of questions that remain with the reader throughout the rest of the day. I ask Koshin what his intention was in doing this and he refers to the riddle of the Sphinx and Oedipus—also discussed in his book and which he learned from his teacher James Helmen—whereby Oedipus solved the riddle of the Sphinx. Although Oedipus felt clever for doing this, his whole life subsequently fell apart. Koshin tells me that the riddle is about what it means to be a human being. He posits that if we solve what it means to be a human being—instead of keeping the questions in front of us—things will really deteriorate “because we think we’ve got something.”

“At the end of each chapter, I didn’t want anyone to finish the chapter and think ‘oh now I get it.’ And they’re very open questions, intentionally, because our lives are not a yes or no situation. I wanted to end these chapters with ‘how do we just keep opening it up? How do we keep keeping it fresh?’ And to me that is incredibly joyful. And as an experience it has been very joyful. To me, the more we can just keep opening things up, opening things up, the more useful, and the more possibilities there are.”

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley Ellison

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley EllisonOne of the points that his anecdotes drive home is that, as human beings, we all struggle in life and in our relationships. “Whether it’s Jesus or Mohammed or the Buddha, they all met difficulty and kept going on.” The same goes for today’s popular superhero movies. “No one would go see those movies if Iron Man was like: ‘it’s too hard and scary’ and so he took off his suit and went back to bed [laughter].”

“We have to be really willing to be in the muck of things. And it’s so much more interesting when we are. . . . Because if we’re not willing to keep opening up, what’s the point? And to me the key is to always open to the freshness of whatever is real and vulnerable in this moment. And how do we attend to it in a loving and tender way, and with some vigor. It’s amazing, I mean to me the willingness to engage is a rare gift. But to really go the distance is the greatest gift. It’s like all the great stories. I always go back to that: the theme is just so powerful. That we love stories, because each of those people they just totally went the distance. They didn’t go part way. So how do we honor what we love in the stories that inspire us? And really take it on. I mean it’s so cool, right? We can totally do that. Wow. We can actually use our life to do that, it’s so amazing. And who knew that it’s completely possible? It really is the coolest thing I know.”

Koshin emphasizes that he is not saying he has arrived. He believes that one is never done cultivating compassion and cultivating being ok. “I think that very often we put teachers in the position that ‘they’ve done it,’ and the way I understand Zen is that we never arrive. Except we can wholeheartedly give ourselves to the practice and screw up lots. There’s an expression in Zen that is ‘fall down seven times, get up eight times.’ And I find that my role as a teacher is also to share how I fall-down—and lately, not even like ‘oh back when I started . . . but now I’ve got it all together.’ I don’t think that’s helpful. To me it’s about watching the practice.”

As a lover of neuroscience, Koshin points out that 80 per cent of our thoughts are repetitive and 90 per cent of our thoughts tend to be based on fear. He feels that meditation is so powerful because it works with the other 10 per cent of the brain, and how to widen that. While many people take their thoughts and their struggles very personally, Koshin asks what it would be like just to realize, “Oh, I have one of those brains that are human brains [laughter].”

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley Ellison

Image courtesy of Koshin Paley EllisonInstead of defending or shaming or blaming someone else, Koshin encourages us to embrace healthy embarrassment and acknowledge that, as human beings, we all fall down and we can get back up. “I mean life is so short. The Diamond Sutra talks of life being like a little bubble in a stream or a flash of lightning in the summer cloud—it’s so beautiful and so amazing and so brief. You know, to watch a flash of lightning in a cloud, it’s amazing. And then it’s gone. So we have this one shot (as far as we know) and this one human life to engage in, and how can we do that with the most compassion, love, and receptivity, and freshness possible? And it looks different for all of us. So amazing.”

References

Ellison, Koshin Paley. 2019. Wholehearted: Slow Down, Help Out, Wake Up. Somerville, Massachusetts: Wisdom Publications.

See more

New York Zen Center For Contemplative Care

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

“Welcome Everything, Push Away Nothing:” Being with the Dying at Zen Hospice Project

United by Our Common Vows: Tenku Ruff on Soto Zen in North America

Maia Duerr: Zen, Life, and Livelihood

A Zen Experience in New York

More from Coastline Meditations by Nina Müller