In Buddhist Studies, a slogan commonly touted by scholars (not only for the sake of academic rigour but also to add some drama to their classes) is that we can never know what the Buddha taught (Wynn, 2007, p. 1). This is, to an extent, defensible from a historical standpoint. Certainly, the tradition teaches of the Middle Way, the Four Noble Truths, and Dependent Origination, but Johannes Bronkhorst admits that is not easy to know the Buddha’s doctrine as he originally proclaimed it, although its aim was certainly to stop suffering and rebirth (Bronkhorst, 2009, p. 58) – something not unique for the Indian thinkers of his period. Due to discrepancies within the early canon, which was itself written at the soonest several hundred years after the Buddha’s Parinirvana, uncertainty in the academy has attained an almost respected aura, as if to protect the dignity and intelligence of Buddhist Studies.

This is a well-intentioned move, to be sure. But the Buddhist tradition is more than just a historical phenomenon. It is not something that simply arose accidentally and had nothing new to say to the human condition. It is a spiritual path communicated by a charismatic personality who was truly traceless. Despite having claimed to hold nothing back in terms of his teaching, the Bhagavan’s face is still shrouded in mystery. Yet despite his tracelessness as the Thus-Gone, he made it clear that there was distinction between exoteric and esoteric doctrine. For the sake of truth, the Lord held no closed fist as a teacher; he never hid any essential knowledge from his Hearers or disciples (DN 16:32). But if we cannot be sure of the exact philosophy of the Buddha, then what did the Blessed One give us? He certainly did not introduce a utopia, nor did he bring about world peace. Apparently, he did not eradicate suffering completely, for there are still sentient beings, and as long as there are sentient beings there is suffering. What were his gifts to the beings of the universe?

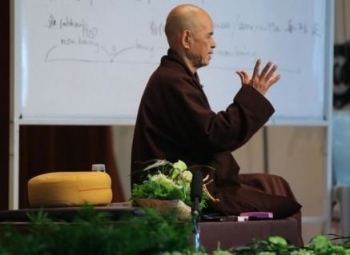

Thich Nhat Hanh is unequivocal about the answer: the Buddha brought compassion (karuna) and wisdom (prajna). He communicated wisdom and compassion to their fullest extent. He brought beings to the realization of the true nature of the transcendent, which demands no sacrifice or blood. Compassion, in particular, was how the Blessed One communicated his nature to a suffering universe. Ethics and morality was as vital in the Lord’s soteriology as insight or wisdom. Specifically, the Buddha saw love (metta) and compassion as crucial means to liberation and Nirvana. Positive values like harmlessness and compassion are absolutely essential to those who wish to take the Buddha’s hand. It was compassion that motivated Prince Gautama to abandon his stepmother, father, wife, and son for a greater purpose. His very preaching was compassion incarnate because he did not need to preach, but loved the universe enough to do so because he wanted to show all beings the path to salvation.

From the Thich Nhat Hanh’s perspective, and indeed the Buddhist perspective, the Absolute is interested in every being and does not have a divine plan for humanity alone. Buddhism, in all its diversity, professes a unified message: that all creatures are capable of enlightenment and liberation. The Perfect One loves all beings without qualification or exception. The Buddha’s compassion is limitless and inexhaustible, so he reveals himself through endless means to bring wisdom to ignorant beings. He fractures his infinite light through the prism of skilful means, and the apparently different lights take on loving, compassionate features of their own. Compassion and wisdom are the faces of the Buddha, and above all these are what he brought, in their fullest revelation, to the universe of samsara, to the worlds of suffering.

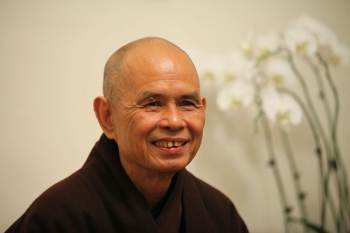

Back to Thich Nhat Hanh Birthday Edition 2012

Back to Thich Nhat Hanh Birthday Edition 2012