FEATURES|COLUMNS|Exploring Chinese Buddhism

Wisdom is Light: An Interview with Venerable Master Miaojiang

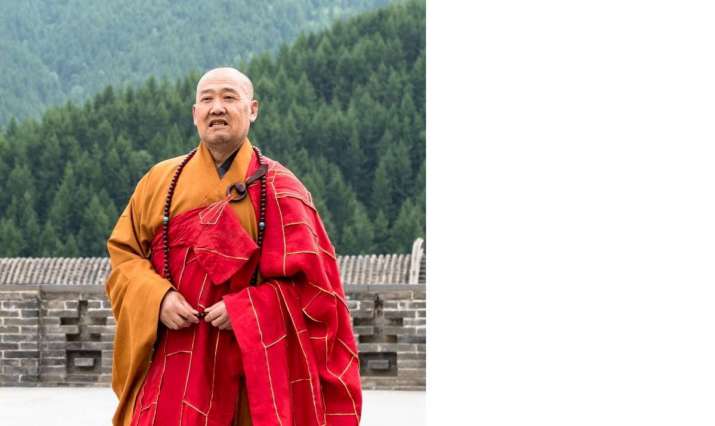

Venerable Master Miaojiang. Photo by Feixue

Venerable Master Miaojiang. Photo by FeixueMy previous article focused on the Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove on Mount Wutai and its abbot, Venerable Master Miaojiang, director of the Buddhist Association of Shanxi Province and deputy director of the Buddhist Association of China. I had an opportunity to sit down with Venerable Miaojiang for an in-depth interview in which he not only shared his views on the Buddhist Association of China, Mount Wutai, and Manjusri’s wisdom, but also revealed much of his personal experience, his childhood, and the masters that helped shape who he is today.

Buddhistdoor Global: Venerable Miaojiang, could you please share your childhood experiences with us? Why did you decide to join the sangha?

Venerable Miaojiang: People join the sangha because of different causes and under different conditions. As for myself, I was perhaps born to be a monk. I was born in 1952 in a village near Datong, Shanxi Province. Today, the village is still there and people are still there. Before I was born, my mother had given birth to nine children, but only two of my sisters survived. My mother was raised as a Buddhist. When she was pregnant with me, she prayed in the local monastery that if the baby was to be a boy, he would join the sangha.

We lived in the southeastern quarter of the village, which was not considered very habitable in the past. As my parents moved from their previous home, on the border of Shanxi and Hebei provinces, to the village, they could only afford to rent a place there. I was born in the second year after the move. My parents turned the place into a very pleasant house with a courtyard. Someone in the village wanted to purchase the house, and while our landlord asked him for 260 yuan, he told us that if we wanted to buy it, he would only ask for 160 yuan. Nevertheless, we could not afford it, so we had to move out in 1962, when I was 11 years old.

Before the age of 11, I had already started learning about and practicing Buddhism. In fact, much of what I say and think now originates from that period. When my family moved, I stayed behind at the local Buddhist monastery. I did not go to school very often and therefore I had to repeat the first grade five times. Eventually, I was ordained in 1968.

I have many fond memories of the village and its environment. In one’s life, there are realms on the outside and realms within. However, it is your mind that creates the world in which you live. During the 18 years from 1962–80, China experienced extreme poverty and people suffered a lot. It was a very difficult time for the Buddhist community, as monasteries were destroyed and the sangha was dispelled. However, I was fortunate enough to have good connections with Buddhist masters and the laity. Even though I was in my teens, they all respected and trusted me. That played an instrumental role in my decision to join the sangha and in my self-cultivation.

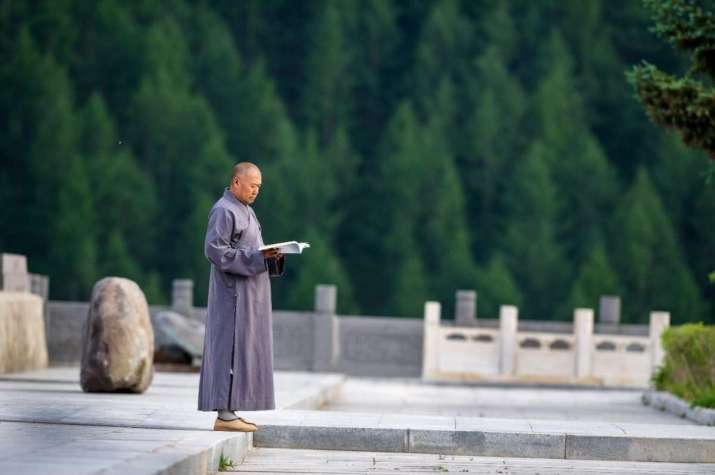

The Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove. Photo by Feixue

The Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove. Photo by FeixueBDG: I have been reading the Biographies of Eminent Monks. Were you inspired by a particular master or a particular sutra?

VMJ: People like to talk about “eminent monks.” I think that as long as one sets his or her mind to the path of cultivation, the path is there for them, and no path is superior to another. People whom you look down upon may have great wisdom. People whom you look up to may not be as great as you think. What you see is often incomplete. All things are changing constantly.

I have never left Shanxi. The farthest place I have moved to is Mount Wutai. All the great masters I know are from this region. When I was little, a senior monk called Venerable Zhaoying taught me a lot about Buddhist doctrines and was very kind to me. He read the Avatamsaka Sutra day and night, and even in his 80s and 90s, he ate only one meal a day. The sutra he read is from the Ming dynasty [1368–1644], and have kept it until today. He had never ridden in a car in his life, and the only time he took a train was in 1929 to commute to Guangji Monastery in Beijing for his ordination. At the end of his life, he expressed the wish to make a pilgrimage to Mount Putuo—Bodhimanda of Guanyin (Bodhisattva Avalokitasvara). I asked him, “Mount Putuo and Mount Wutai, which is further away?” He said, “Mount Putuo should be closer as Guanyin should be closer to us. Manjusri and Mount Wutai are further away.” I then suggested that we go to Mount Wutai instead. He responded immediately, “What about transportation? I can pay for myself, I have some savings,” pointing to his bedsheets. I turned the bedsheets over and found only 12.5 yuan. Those were his life savings. He checked with me whether it was enough and I reassured him that it was enough to travel anywhere. When I took him to Mount Wutai by car, he enjoyed it very much. I asked him whether he wanted to make another visit to Mount Putuo, but he declined as he already felt content. When he passed away, he had no patrons or disciples, but he was a great master to me. Eminent monks are not necessarily surrounded by people. They can be ordinary, and sometimes they may be even looked down upon by society. With the 12.5 yuan he saved, not to mention Mount Putuo, he could go to all the worlds in the Ten Directions.

I also think of my own master, Venerable Zangtong. If he were still alive, he would be more than 100 years old now. He did not talk much; neither was he particularly eloquent. He devoted much of his life to reciting three sutras: the Bhaisajyaguru Sutra, the Diamond Sutra, and the Avalokitesvara Sutra. When he passed away at the age of 81, he still held a sutra in his hand. Venerable Sanyi, the master of my master, served as the 5th and 6th director of the Buddhist Association of Shanxi (I am the 8th director). He passed away on his birthday—the 23rd day of the first lunar month. That morning, he gave his attendant disciple a day off. He cleaned his room himself, took a shower, and put on his robe. At noon, some officials and lay Buddhists came to visit him, as they had been told he was ill. When they went to bring him lunch, they found that Venerable Sanyi had passed away. One ought to come to the world in a natural state, and leave the world in a liberated way. When ultimate nirvana is reached, there is no arising or ceasing. When you are alive, you do not feel life; when you are going to die, you do not feel death.

Many Buddhist masters were like that, when I grew up. One joins the sangha to restore one’s true nature. Nowadays, monastics gain knowledge from Buddhist academies, but their faith sometimes decreases. I am not saying Buddhist academies are not good, but if one enters a higher intellectual level without learning right conduct as a foundation, one tends to develop a sense of pride and an eagerness for fame and profit.

Since the Open Door Policy of the 1990s, our lives have been drastically transformed. China is developing so fast, and in just a few decades, we have achieved what the West achieved in over 100 years. This time is a test for monastics, to the Chinese people, and to our society as a whole. If you are conscious, spiritually aware, and awake, this is the best time to grow and succeed. It is like the smelting process; if you can stand a high temperature, you will be stronger than a vajra. If one drowns oneself in the pursuit of fame and profit, one would only burn to ashes.

Venerable Master Miaojiang. Photo by Feixue

Venerable Master Miaojiang. Photo by FeixueBDG: What is the role of the Buddhist Association of China?

VMJ: The precursor to the Buddhist Association of China was the Buddhist Association of the Republic of China, founded at the end of the Qing dynasty [1644–1912]. The current Buddhist Association of China was created in 1953 by Buddhist leaders, such as Zhao Puchu, Venerable Yuanying, and Venerable Xuyun. They were innovative and far-sighted. After the establishment of the Buddhist Association, Daoist, Islam, and Christian communities in China followed to found their own associations.

The Buddhist Association functions as a communication channel between the government and the Buddhist community. It is responsible for passing on national policies and laws, and for coordinating their implementation. Meanwhile, the association reports and solves the concerns of the Buddhist community, discovers talents, educates people, improves society, and so forth.

In China, we believe that when a family is harmonious, all affairs are proper. The Buddhist community here is a big family, too. We can make great contributions. Chinese Buddhists care about our nation as well as following Buddhism. This is our duty, and it is also in accordance with Buddhist teachings. People from abroad may have little contact with the Chinese Buddhist Association or its chapters at the provincial level. To improve this situation, we have increased our exchange with religious organizations within and beyond Asia, in the past few years. The Great Sage Monastery of Bamboo Grove has organized international conferences and events, and our friends from different parts of world have gained new understandings of Chinese Buddhism and of China.

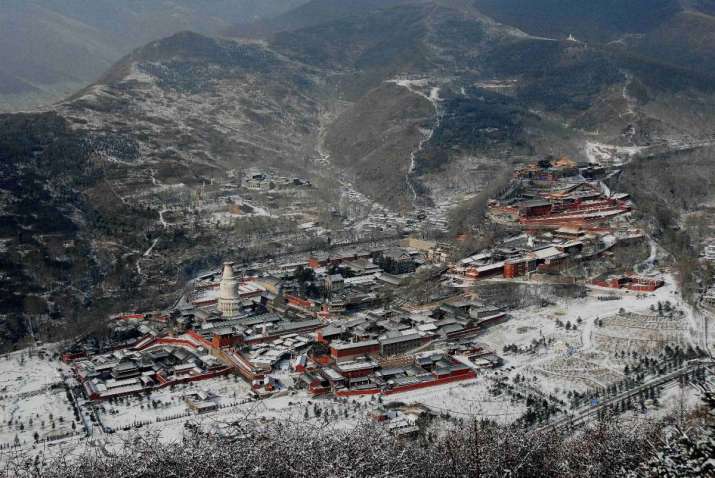

BDG: Mount Wutai is often praised as the foremost among the “Four Sacred Mountains of Buddhism” in China. How do you see its history and significance?

VMJ: Mount Wutai has indeed been highly regarded among the Four Sacred Mountains for more than 1,000 years. It is the only Chinese holy site described in ancient Indian texts. As the bodhimanda of Manjushri, Mount Wutai has been a major Buddhist pilgrimage site throughout history. Before the Song dynasty [960–1279], different regions across China set up their own Mount Wutai to facilitate pilgrimage and worship. Embodying wisdom, Manjushri is also revered by Buddhists in Tibetan regions, and in India, Nepal, Mongolia, Korea, and Japan.

Today, we feel very honored to live on Mount Wutai. Buddhists from all over the world continue to make pilgrimages to Mount Wutai. This morning, we received a group from Taiwan. There are many ways for a society to develop or for a culture to be disseminated. It can be through wars, trade, or religion. The spread of Buddhism relied completely on faith. It was spread from one person to the next, and the process did not cause any wars. Mount Wutai is situated on the border between the Han Chinese and other ethnic groups. It has played a very beneficial role in cultural exchange and Buddhist dissemination.

Mount Wutai. Photo by Jiao Jinqi

Mount Wutai. Photo by Jiao JinqiBDG: Could you please explain the wisdom of Manjushri to us? How can we practice Manjushri’s wisdom in our daily lives?

VMJ: Among the inhabitants of Mount Wutai, we often discuss what wisdom is. In the Buddhist community, there are different interpretations too. In my view, wisdom is to spread positive energy and to be selfless. That means serving other people and doing good things for society. Wisdom is light. Everyone has light to give, although there may be more or less depending on one’s capacity. Nevertheless, when others receive something good from you, they receive light. In Chinese, there is an expression “zhan guang” (touch light), which means “benefitting from others.” Such light represents the wisdom of the bodhisattva Manjushri. The great wisdom of Manjushri is to benefit all sentient beings without asking anything in return. It manifests itself in both doctrine and practice. In fact, all bodhisattvas enlighten sentient beings with wisdom. For instance, Kṣitigarbha made the following vows in front of the Buddha, “From now until incalculable kalpas in the future, I will use many different skilful means to liberate the suffering sentient beings in the Six Realms before I realize Buddhahood myself.” Of course, we humans have wisdom and positive energy, too. When you interact with other people, if you offer your good qualities and good things, it is wisdom. If you give out bad things, that is darkness, which in Buddhism terms is called affliction. Do not bring affliction to others—that’s wisdom.

I would like to express my gratitude to Gao Haiqin for transcribing the interview and to Venerable Yihu for editing the Chinese transcript.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global