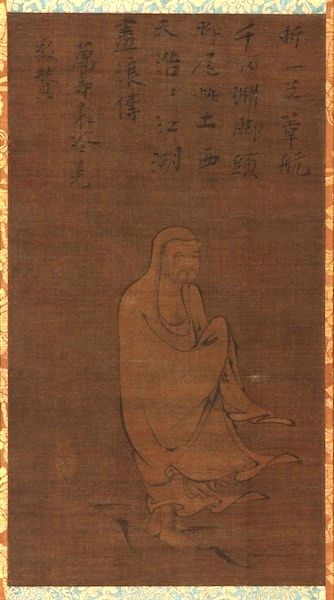

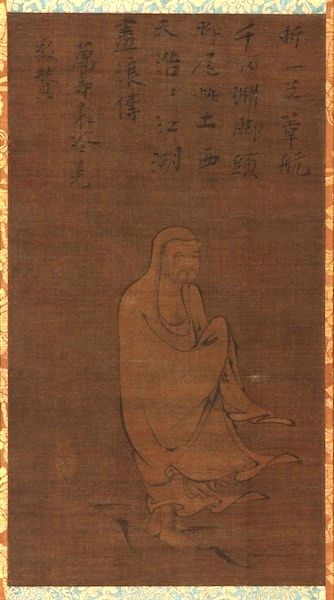

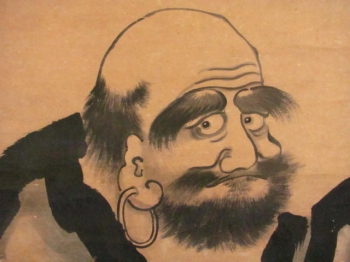

them stay awake during meditation. When Japanese Buddhists learned of this practice many traveled to China to study it, drank plenty of Chinese tea, and then transmitted both traditions back to Japan. Just as Bodhidharma supposedly floated along the river on a reed, Chan Buddhism and powdered tea drinking were carried across land and sea from one culture to another, landing in Japan in the late 12th century and changing its culture forever.

“Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi on a Reed”. Japan, Muromachi period, 15th century. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, F1907.141

The impact of meditational Buddhism and tea drinking on Japanese society was so profound that many of us associate both tea and Chan, or Zen, with Japan more than with India or China. Both of these cultural traditions were embraced by the Japanese military class, which ruled Japan from the late 12th century to the modern age. Having essentially usurped the political power of Japan’s imperial court, these shogun and samurai adopted many Chinese practices and cultural pursuits in order to become or at least appear more sophisticated. Zen, Tea, and Chinese Art in Medieval Japan focuses on the artistic developments of this period of intense cultural borrowing and adaptation. Using Chinese and Japanese tea bowls, flower vases, scroll paintings, lacquerware, and other objects from the Freer’s own collection, it explores the importance of Zen Buddhism and tea in shaping Japanese cultural and aesthetic sensibilities.

In Japan, tea, Buddhism, and a fascination with Chinese culture have been profoundly connected. Tea was first introduced to Japan from China in the early Heian period (794–1185) during a period of intense fascination with the culture of Tang dynasty China (618–907). Early Japanese students of Buddhism braved the sea journey to China to learn about Buddhist scriptures and acquire aids on the path to enlightenment from their spiritually advanced neighbors. One monk, Saicho (767–822), the founder of the Tendai school of Japanese Buddhism, is said to have brought tea back to Japan with him in 805 and distributed seeds for planting around the capital, Heian-kyo (now Kyoto). The Chinese beverage, which was then flavored with spices and salt, found favor with Emperor Saga (r. 809–23) and was enjoyed by courtiers, who found that the drink went particularly well with the favorite pastime of composing Chinese-style poetry. However, in the final years of the 9th century, Japan broke off official links with the increasingly fragile Tang court and commenced a period of cultural introspection. Tea, with its continental associations, fell out of favor at court, and was not particularly popular in Japan for the next 300 or so years.

In the early Kamakura period (1185–1333), however, Japan was again drawn to its powerful neighbor, this time China of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Tea was reintroduced to Japan, again by a Buddhist monk, Eisai (1141–1215), who was among those who journeyed to China to study Chan. In 1191, he returned to Japan determined to propagate meditational Buddhism and extolled tea drinking as a way to prolong life. Eisai promoted the new Song-style tea, for which the leaves were ground into a fine powder and mixed with water, which was whipped into a frothy consistency. Although China saw the decline of tea drinking under the rule of the Mongols in the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), the custom gained momentum in Japan, spreading gradually outwards from the Zen temples and into the residences of the samurai warrior leaders, who incorporated the simple brew into their extravagant lifestyles.

When the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) replaced the Mongols as rulers of China, tea drinking re-emerged in China, but in yet another form: that of leaves steeped in hot water. It is interesting, however, that around this time in Japan the drinking of Song-style powdered tea began to develop into what is generally known as the tea ceremony, or chanoyu. A crucial factor in this development was the vogue for karamono, or “things Chinese,” which appealed to the Japanese military elite’s taste for the exotic and the extravagant. Particularly coveted were paintings and calligraphy by Chinese masters, bronze vases, lacquer cup stands and trays, and fine ceramic items, including vases, tea caddies, and tea bowls. During the Muromachi period (1336–1574), in response to the great influx of Chinese goods, the Ashikaga shoguns appointed doboshu, or connoisseurs, to authenticate and catalogue these objects and also to formulate rules for their display. It was these men of culture, most notably Noami (1397–1471) and Soami (d. 1525), who developed tea drinking into a more elaborate social ritual, serving tea to the guests of their samurai masters in elegant rooms adorned with Chinese artifacts.

This connection between tea, Zen, and the admiration of Chinese culture is at the heart of the Freer exhibition, which presents outstanding examples of the types of Chinese artifacts that were collected and coveted by Japan’s military elite to display in their homes and use in the tea ceremony. Typically, these karamono were displayed in the main reception room of a military lord’s residence, within a special recessed alcove called a tokonoma, a sort of shrine to art. Scroll paintings were hung on the wall of the alcove, and a flower vase or another vessel crafted from metal, ceramic, or lacquer was placed on the floor. Among the vessels that graced the tokonoma were high-quality Longquan celadons like the late 13th- or early 14th-century vase in the exhibition. In China, such a vase might have held flowers offered to a Buddhist deity on an altar. Similarly, a Chinese carved lacquer box in the exhibition is typical of the rare and spectacular objects that would have been collected by the military and displayed to impress guests.

Mallet-shaped vase. Probably Dayao kiln, Longquan, Zhejiang province, China, Southern Song or Yuan period, late 13th–early 14th century. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, F1937.18

Round lidded box with figures in landscape. China, Ming period, Yongle reign (1403–24). Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, F1953.64a-b

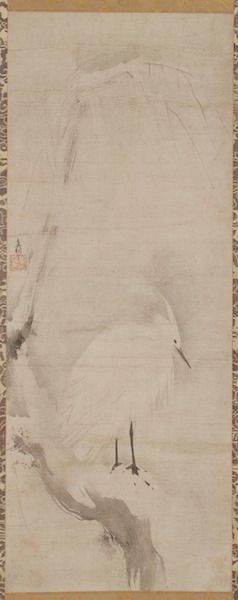

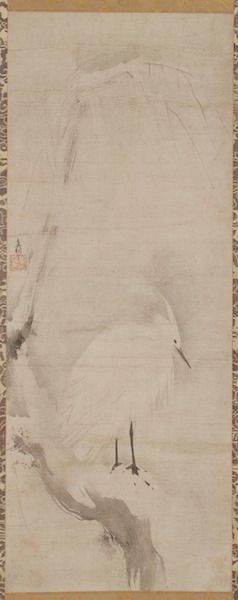

The most important object in the tokonoma was the hanging scroll. Usually a painting but sometimes a calligraphic inscription, these scrolls typically featured a mountain landscape or a bird-and-flower scene, two of China’s principal painting genres. Others were by Chinese Chan artists and depicted themes relating to spiritual awakening. So popular were Chinese paintings that Japanese artists traveled to China to study monochrome painting techniques, and upon their return to Japan formed studios dedicated to Chinese-style painting, which were patronized by the military elite. Though many of their works echoed the styles and subjects of traditional Chinese paintings, they did eventually incorporate native Japanese subject matter, motifs, and poetic influences. The painting White Heron on a Snowy Willow is an elegant example of the mastery of the Chinese painting style by the Japanese artist Soami, one of the doboshu connoisseurs who greatly influenced the aesthetic evolution of the tea ceremony, as well as interior and garden design. The predominance of white space in this work shows the influence of earlier Chinese Chan artists such as Muqi Fachang (1216?–69?).

Soami (d. 1525), “White Heron on a Snowy Willow.” Japan, Muromachi period, mid-15th–early 16th century. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, F1977.2

Undoubtedly the most important of all the karamono objects admired in Japan in this period were the dark, iron-glazed tea bowls named Temmoku for the Tianmu mountain temple in China where they were used to drink tea. Shiny and black, with subtle patterning created by the iron oxide in the glaze, these bowls were not particularly valued in China, a nation already known for its pure white porcelain. In Japan, however, they were at the heart of the tea ceremony and came to represent the spirit of tea, which had become deeply infused with the Zen qualities of simplicity, austerity, and spontaneity. The simple black tea bowls, brought from the Chan temples of southeastern China, eventually set the tone for the tea ceremony, which from the 16th century on, under the influence of several tea masters including the celebrated Sen Rikyu (1522–91), favored the simple, humble, and austere over the refined, grand, and ostentatious. Eventually, the Japanese became less interested in karamono and began to pay more attention to treasures made in their own country; Zen Buddhism and tea drinking thus became something very distinctly Japanese.

Zen, Tea, and Chinese Art in Medieval Japan continues at the Freer Gallery of Art until 14 June 2015.

Meher McArthur is an Asian art curator, writer, and educator based in Los Angeles. She has curated over 20 exhibitions on aspects of Asian art. Her publications include Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols (Thames & Hudson, 2002), The Arts of Asia: Materials, Techniques, Styles (Thames & Hudson, 2005), and Confucius: A Biography (Quercus, London, 2010; Pegasus Books, New York, 2011).

Bodhidharma. From kakemonoarts.com

Bodhidharma. From kakemonoarts.com