FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

Zen Buddhist Aesthetics in the Works of Joanne Julian

Raven for PN (detail), by Joanne Julian. 2010, graphite and ink on Arches paper. Image courtesy of the artist

A mixed-media work on paper depicting a jet-black raven emerging from a bold black splash of ink poetically and powerfully exemplifies the work of Los Angeles-based artist Joanne Julian. For over 30 years, Julian has been a master of both meticulously detailed drawings and spontaneous Zen-style calligraphic brushwork, and throughout her career has created her own trademark mixed-media works that blend the two, bringing together what are generally considered to be contrasting or opposing styles. One, painstaking and controlled, is associated with Western artistic practice; the other, vigorous and spontaneous, is connected to East Asia, and particularly to Zen brush-painting. Because Julian has embraced both of these artistic worlds fully throughout her career, her work enables the two distinct styles to coexist harmoniously.

Born of Armenian parents, Julian grew up with a strong immigrant work ethic and with parents who were strict disciplinarians. Her ancestors had been lace-makers and her grandparents were tailors, a profession in which precision is critical. Despite her parents’ concerns, she chose to study art, gaining an MA from California State University, Northridge, and an MFA from Otis Art Institute of Parsons School of Design, but as a student, and throughout her career, she has displayed the discipline of her family upbringing. Julian attended Otis during the 1970s, a time when the focus was on composition, rendering, and exactitude, and her rigorous training under masters of both draftsmanship and abstract expressionism guided her towards a career that has centered both on meticulous control and unharnessed expression. In addition, in one of her college print classes, she became intrigued by Japanese woodblock prints. Traveling to Japan in the late 1970s and watching Japanese Zen masters painting and doing calligraphy, she was deeply and enduringly inspired by the country’s art, culture, and spirituality.

Little Koi, by Joanne Julian. 1990, acrylic, monoprint. Private collection. Image courtesy of the artist

Japanese influence pervades Julian’s drawings and prints of koi fish from the 1990s to the present. In her Fish series of monoprints (single impressions of a printable image), she splashes paint onto the paper and then prints an image of the fish on top of the dry paint. In these works and in later watercolor-tinted drawings of fish, she gives the creatures volume and character with her finely detailed lines but allows them to swim in the vastness of an empty ground, either plain white or bold black or a delicate celadon. According to Zen Buddhist teachings, when fish go through water, there is no end to the water no matter how far they go. When birds fly in the sky, there is no end to the sky no matter how far they fly. Yet, neither fish nor birds have been separated from the water or sky. In Julian’s works, the fish swerve and curve gracefully through space, at once representational and iconic. They are carefully formed by lines but then liberated by space in a visual expression of a Zen koan, or riddle.

Although Julian is not a Buddhist, she has incorporated many aspects of Zen spirituality and aesthetics into her work. In many of her pieces, including the Birds series, she includes bold calligraphic strokes and splashed ink, reminiscent of the Zen painters’ haboku, or “flying ink,” often alongside minutely detailed feathers or faces. She also embraces asymmetry and vast areas of white, “negative” space, allowing her subjects to breathe and expand. Over the years, Julian has also borrowed Zen symbolism in her paintings, most notably the enso, or Zen circle. Formed with a single brushstroke to represent the entirety of the universe captured in one single, spontaneous stroke, the enso is used as a visual aid by Zen Buddhists in their meditational practice and pursuit of enlightenment. Julian’s steady and disciplined hand, which can produce a single stroke in one breath, has enabled her to create many enso over the decades, in black ink on white, white on black, red on white, and even gold on black and white.

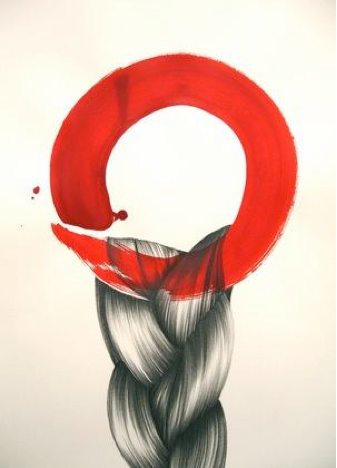

Angela’s Braid, by Joanne Julian. 2005, acrylic and graphite on Arches paper. Image courtesy of the artist

Her most interesting enso, however, painted mostly in the 2000s, are those in which she toys with the circle, allowing it to interact and sometimes become tangled with other motifs. In one 2005 image, Angela’s Braid, the circle becomes a ring to which what appears to be a thick braid of hair is tied (though in fact the braid was inspired by the large, twisted-straw ropes that mark sacred spots in Japan’s Shinto tradition), while in another work, it is a red circle hidden behind a delicate black veil—both of which suggest a femininity restrained. In others, koi fish swim or gingko leaves tumble gently through the circle and abstract elements like sticks and blocks of color merge with it—all of which visually blend power and playfulness to imply perhaps that enlightenment might be closer to us all than we think.

Zen Circle with Sticks, by Joanne Julian. 2009, acrylic, collage, graphite, and ink on Arches paper. Image courtesy of the artist

The themes of hair, fish, Zen circles, and birds have recurred and interacted throughout Julian’s career, rendered with a graceful blend of refinement and emotion. In her latest series, Botanicals, executed from 2009 to the present, Julian follows a path through meadows, woods, and rainforests into the astonishingly sensual realm of plants. Although she is not the first artist to make plants sexy, her Botanicals exhibition, to be held at Cal State Northridge’s Valley Performing Arts Center Gallery near Los Angeles from 19 September to 28 October this year, will show ferns, palm fronds, banana leaves, and lilies depicted with exquisite detail in red and green Prismacolor, as luscious and deliciously sensuous as a torn-open fig.

Though she admits freely to the influence of Japan and Zen aesthetics on her work, Julian gives credit to her own heritage, too, explaining, “I like to think the Mid-eastern part of me anticipates or adds some passion to the Japanese breath-holding or restraint.” Again, the cropping of the plants, their asymmetrical placement, and the abundance of white space borrow from Japanese aesthetics, but the soft textures and dramatic tones of the leaves and flowers are all her own, evolved from discipline and dynamism and years of artistic practice and pure passion.

(This article was adapted from an article written by the author for KCET Artbound - Flawless Fluidity in the Works of Joanne Julian. More work by Joanne Julian can be found on her website, http://www.joannejulian.com.)