NEWS

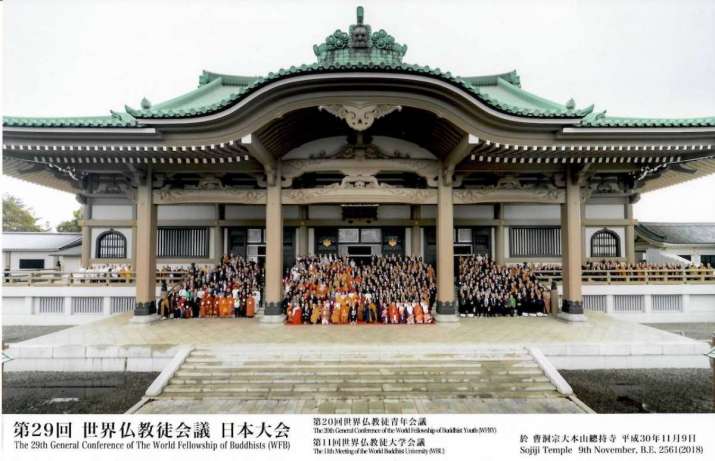

29th General Conference of the World Fellowship of Buddhists held at Soji-ji Temple, Yokohama

Conference attendees at Soji-ji Temple. Image courtesy of Miranda Chen

Conference attendees at Soji-ji Temple. Image courtesy of Miranda ChenFrom 5 to 9 November, the 29th General Conference of the World Fellowship of Buddhists (WFB) was held at the great temple (daihonzan) of Soji-ji in Yokohama and the Marroad International Hotel Narita in Narita, Chiba Prefecture. The Japan Buddhist Federation (JBF) hosted the conference. Speakers included Roshi Joan Halifax, Rinzai-shu leader Jyotetsu Nemoto, and chief priest of Daizen-ji, and Taiko Kyuma, head of the All-Japan Young Soto Zen Buddhist Association.

The conference’s theme was “Creating hope in life and death.” Joan Halifax spoke on “The Strange and Necessary Case for Hope.” In her speech, she proposed: “As Buddhists, we know that ordinary hope is based in desire, wanting an outcome that could well be different from what might actually happen. . . . If we look at hope through the lens of Buddhism, we discover that wise hope is born of radical uncertainty, rooted in the unknown and the unknowable.” She contextualized hope in her vision of socially engaged Buddhism, for which she is particularly well known in the US. In particular, she discussed how “wise hope” could facilitate a life of dignity and quality in end-of-life care and prison chaplaincy.

Speakers at the 29th WFB Conference 2018. Image courtesy of Miranda Chen

Speakers at the 29th WFB Conference 2018. Image courtesy of Miranda ChenIn his presentation “Buddhism: Help for the Living,” Jyotetsu Nemoto spoke about the social problems facing Japan, including bullying, unemployment, social withdrawal, poverty, and elderly care. He argued that suicide was the leading cause of death among young people, and that social media—itself commonly accused for exacerbating feelings of isolation, envy, and dissatisfaction among users—was filled with expressions of negativity and even inclinations toward self-harm. In his speech, he looked back on the 14 years he spent ministering to suicidal individuals and bereaved families, arguing that exploring answers to feelings of hopelessness and the wish to die or disappear are an essential part of healing.

Taiko Kyuma’s speech was titled “Despair and Hope in Disaster Areas from the Perspective of a Faith Leader.” He focused on the process of psychological recovery from 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami, which claimed the lives of 15,896 people, injured 6,157 people, and continues to affect the lives of people today. He discussed the physical and psychological situation of children in disaster areas, and how faith leaders tried to keep a spotlight on the recovery process of affected communities even as memories began to fade in other regions and Japanese media lost interest. The building a sharing, caring society, especially after the trauma of a natural disaster, required wisdom and empathy to rebuild the social ties that had existed before the event while not causing unnecessary emotional distress.

Conference attendees. Image courtesy of Miranda Chen

Conference attendees. Image courtesy of Miranda ChenThe general conference concurrently ran alongside the 20th General Conference of Buddhist Youth (WFBY) and the 11th Meeting of Thailand’s World Buddhist University (WBU).

The host of the three meetings, the JBF, was founded in 1900 and today counts 59 Buddhist denominations, 36 prefectural Buddhist associations, and 10 Buddhist organizations among its members, with over 70,000 temples and monasteries belonging to groups under the JBF banner. It holds membership of the WFB. Founded in 1950 in Colombo and currently based in Bangkok, the Fellowship is one of the world’s most senior contemporary ecumenical Buddhist federations, consisting of nearly 200 regional centers in 41 countries. The WFBY, also founded in 1950, was created to broaden and deepen young people’s understanding of Buddhism through exchange programs and leadership training courses. The All Japan Young Buddhist Association (JYBA) is one of the WFBY’s 42 groups and is based in 16 countries.

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Japanese Temples Redistribute Donations to Fight Child Poverty

Repurposed Japanese Temple Candles Provide Light for Underprivileged Children

Mayor of Hiroshima Appeals for a World Free of Nuclear Weapons at Interfaith Memorial Ceremony

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

How to Want What You Already Have: A Practice for Taking Life As Granted Rather than For Granted