NEWS

Archaeologists Shed Light on Ancient Khmer City Lost in the Cambodian Jungle

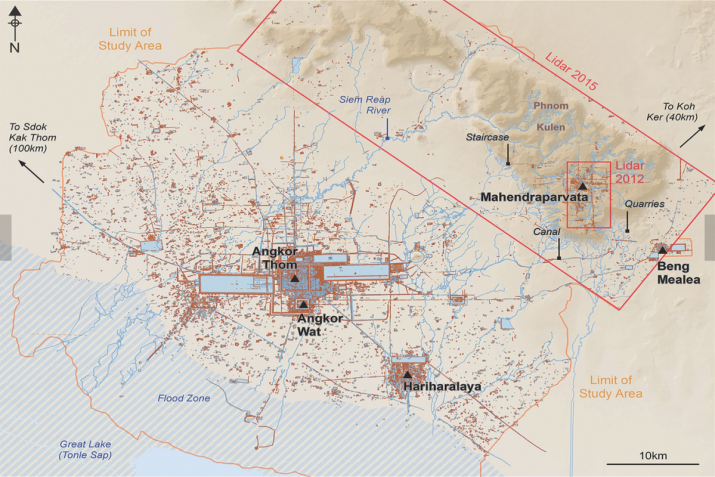

A map showing the study area surrounding the ancient Khmer capital of Mahendraparvata in relation to Angkor Wat. From newsweek.com

A map showing the study area surrounding the ancient Khmer capital of Mahendraparvata in relation to Angkor Wat. From newsweek.comArchaeologists in Cambodia have shed new light on the ancient Khmer city of Mahendraparvata, engulfed for centuries by the Cambodian jungle. Using airborne laser-scanning technology, researchers have successfully mapped the capital of the early Khmer empire and a forerunner of the famed Angkor Wat, with the results of their work detailed in a new research report published on Tuesday in the science journal Antiquity.

Researchers from the French Institute of Asian Studies and Cambodia’s management authority for Angkor Archaeological Park—known as APSARA—have used light detection and ranging (LiDAR) surveying technology to reveal the location and details of Mahendraparvata. While the existence of the ancient city has been known for decades, concrete archaeological data has been scant, and the new paper—the result of a years-long international research project—offers the most definitive identification yet of Mahendraparvata.

“Despite its importance as the location of one of the Angkor period’s earliest capitals, the mountainous region of Phnom Kulen has, to date, received strikingly little attention. It is almost entirely missing from archaeological maps, except as a scatter of points denoting the remains of some brick temples,” the researchers said in their findings. “This research yields new and important insights into the emergence of Angkorian urban areas.” (Antiquity)

Sometimes dubbed the “lost city of Cambodia,” Mahendraparvata, the name of which is derived from Sanskrit and means “Mountain of the Great Indra,” is located 40 kilometers north of the famed Angkor Wat complex, on the slopes of Phnom Kulen mountain in Cambodia’s northern province of Siem Reap. An early capital city of the Hindu-Buddhist Khmer empire that flourished in Southeast Asia from the 9th–15th centuries. The city’s name refers to the sacred hilltop, today known as "Phnom Kulen,” where the first king of the Khmer Empire, Jayavarman II (r. 802–35), was consecrated in 802.

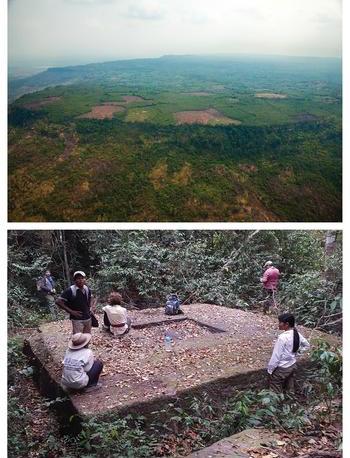

Top: an oblique aerial view of the Phnom Kulen escarpment

and plateau. Bottom: an example of a newly documented

temple site in the forests of the Phnom Kulen region.

From cambridge.com

“The Phnom Kulen capital ruled at the end of the eighth century and first half of the ninth century,” explained Jean-Baptiste Chevance, an archaeologist from the Archaeology & Development Foundation—Phnom Kulen Program. “Radiocarbon dating results confirm this occupation, corresponding to the reign of [King] Jayavarman II.” (Newsweek)

One of the reasons for the previous dearth of archeological evidence for Mahendraparvata is because limited accessibility has hindered research projects.

“The history and geography of the area has amplified many of the problems of conducting archaeological survey and mapping in Cambodia: until recently, the site was remote, difficult to access and covered with dense vegetation,” the research paper reveals. “Furthermore, it was among the last bastions of the Khmer Rouge, who occupied the area from the early 1970s until the late 1990s. Dangerous remnants of war, such as land mines, remain a serious problem.”

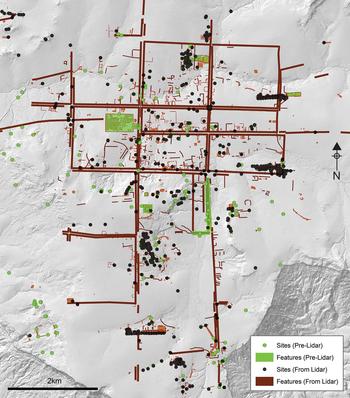

Using a series of rigorous aerial and ground surveys that began in 2012, the team of researchers mapped out an extensive network of ancient urban development that they believe dates from the ninth century, including thousands of previously undetected archaeological features that had been engulfed by centuries of dense vegetation. LiDAR surveys have revealed a complex urban network of city features designed in a grid-like pattern and spanning some 50 square kilometers.

“The ancient Khmer modified the landscape, shaping features on a very large scale—ponds, reservoirs, canals, roads, temples, rice fields, et cetera,” said Chevance. “However, the dense forest often covering the areas of interest is a main constraint to investigating them.” (Newsweek)

Map of the newly discovered main axes of Mahendraparvata,

and comparing the pre-lidar and post-lidar mapping.

From cambridge.org

The team found also found raised embankments running roughly in line with the four cardinal directions, with traces of buildings, including temples and palaces with within each city grid square.

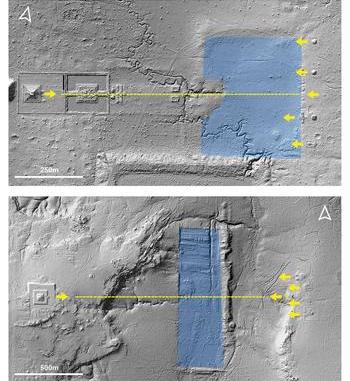

“It shows a degree of centralized control and planning,” said Damian Evans of the French Institute of Asian Studies in Paris, compared with other Khmer cities from the period, which grew organically. “What you’re seeing at Mahendraparvata is something else. It speaks of a grand vision and a fairly elaborate plan.” (New Scientist)

As far as we can tell, added Evans, “this king [Jayavarman II] is the beginning of the Khmer Empire and this is his capital.” (New Scientist)

This area is “crucial for understanding the historical trajectory of Angkor and the Khmer empire,” the researchers said in their findings. “This would place the site among the first engineered landscapes of the era, offering key insights into the transition from the pre-Angkorian period, including innovations in urban planning, hydraulic engineering, and sociopolitical organization that would shape the course of the region’s history for the next 500 years.” (Antiquity)

Similar surveying techniques have also been employed to reveal the extent of the sprawling Angkor Wat complex. In 2015, a team of archaeologists discovered a number of buried towers and the remains of a huge structure of unknown function near Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious monument. The discoveries, which also include what appear to be residential structures and wooden fortifications, suggest that the ancient Buddhist complex is far larger than previously thought.*

Covering an area of some 400 square kilometers, Angkor Archaeological Park is one of the most important archaeological sites in Southeast Asia, containing the remains of several capitals of the Khmer empire among the landmarks that mae up the celebrated Angkor Wat complex. A protected UNESCO World Heritage Site, the area also includes Angkor Thom, the last and most enduring capital of the Khmer empire. At its height, the city complex and hundreds of temples were home to more than a million inhabitants, making it one of the most populated pre-industrial centers in history. Large areas of the park have been excavated over the decades, creating an immersive archaeological wonder that draws more than two million visitors each year.

Axis and orientations of the central pyramid, reservoir, and

associated shrines at Koh Ker, top, and Mahendraparvata,

bottom. From cambridge.org

Buddhism is the official religion of modern-day Cambodia, with 96.9 per cent of the country’s population of 14.14 million people following Theravada Buddhism, according to data for 2010 from the Washington, DC-based Pew Research Center. Islam (2 per cent), tribal animism (O.5 per cent), and Christianity (0.4 per cent) represent the bulk of the remainder. According to Cambodia’s Ministry of Cults and Religious Affairs, there are 59,516 Buddhist monks and 4,755 monasteries in Cambodia.

* Newly Discovered Structures Suggest Angkor Wat is Larger than Previously Thought (Buddhistdoor Global)

See more

Mahendraparvata: an early Angkor-period capital defined through airborne laser scanning at Phnom Kulen (Antiquity)

Ancient jungle capital of the Khmer Empire mapped for the first time (New Scientist)

Ancient 'Lost City' of Khmer Empire Rediscovered Hidden Under The Cambodian Jungle (Science Alert)

Long Lost Ancient City Uncovered Deep In Cambodian Jungle (Newsweek)

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Senior Cambodian Minister Urges Greater Buddhist Involvement in Society

Cambodian Buddhists in Rhode Island Observe Traditional Khmer New Year

Monks and Activists Hold Buddhist Ceremony to Address Deforestation in Cambodia

Cambodian Monastics Gather in Phnom Penh for 24th Annual Congress

The Cambodian School that was Built from Garbage

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhistdoor View: Buddhism in Southeast Asia: a Catalyst for Civic Exchange

Stepping into the Mandala – A Journey to Ankor Wat

Salvation Centre Cambodia — Fighting HIV/AIDS with the Buddha’s Army