NEWS

San Antonio Museum of Art Examines Salvation and Retribution in Pure Land Buddhism

By Craig Lewis

Buddhistdoor Global

| 2017-06-19 |  Amida Buddha with Attending Bodhisattvas. Wood sculpture adorned with gold, pigment, and metal. Japan, late 18th century. From expressnews.com

Amida Buddha with Attending Bodhisattvas. Wood sculpture adorned with gold, pigment, and metal. Japan, late 18th century. From expressnews.comThe San Antonio Museum of Art in Texas is hosting the first exhibition in the United States to explore in detail Pure Land Buddhism, one of the most widely practiced Buddhist traditions in East Asia. Heaven and Hell: Salvation and Retribution in Pure Land Buddhism, which runs from 16 June–10 September, features more than 70 paintings, sculptures, and other works of art from the Pure Land school, along with artifacts from the museum’s own permanent collection.

Dr. Emily Sano, senior adviser for Asian art at the San Antonio Museum of Art. From expressnews.com

Dr. Emily Sano, senior adviser for Asian art at the San Antonio Museum of Art. From expressnews.comCurated by Dr. Emily Sano, the Coates-Cowden-Brown senior advisor for Asian art at the museum, the exhibition brings together some of the most stunning examples of works created for the devotional and funerary traditions of Pure Land Buddhism, drawn from 20 private collections and institutions across the world, including the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“It’s about Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise and the Pure Land sect of Buddhism, which is related to, but different from, Zen [Chan] Buddhism,” said Dr. Sano. “Amitabha grants salvation in paradise if you just say his name. Many people were attracted to this concept.” (San Antonio Magazine)

Dr. Sano, a former director at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco who joined the San Antonio Museum of Art last year, explained that she drew inspiration for the exhibition from the museum’s permanent collection, which includes sculptures of Amitabha, the Buddha of Western Paradise that is central to the Pure Land faith. “I wanted to feature a certain sect of Buddhism to help the audience understand,” she said. “I’m a specialist in Japanese art. The strength of the artwork attracts me to the subject matter. I think the beauty will impress people. What surprised me is that Buddhism has a concept of hell. The difference here is that hell isn’t forever; you can get out.” (San Antonio Magazine)

Shrine (butsudan), Japan, Edo period, c. 1800. Wood, lacquer, pigment, gilt, and metal. Photo by Sean Pathasema. From artdaily.com

Shrine (butsudan), Japan, Edo period, c. 1800. Wood, lacquer, pigment, gilt, and metal. Photo by Sean Pathasema. From artdaily.comPure Land Buddhism first came to prominence in China with the founding of Donglin Monastery on Mount Lu in Jiangxi Province, southeastern China, by the renowned teacher Master Huiyuan (334–416) in 402 CE, and was later systematized by Master Shandao (613–81). Pure Land teachings focus on Amitabha Buddha and are based on three principle texts: the Longer Sukhavativyuha Sutra (Infinite Life Sutra), the Shorter Sukhavativyuha Sutra (Amitabha Sutra) and the Amitayurdhyana Sutra (Contemplation Sutra). Pure Land practices and concepts are found within basic Mahayana Buddhist cosmology and form an important component of Mahayana traditions in China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Tibet. One of the principal practices of Pure Land Buddhism is the recitation of the name of Amitabha Buddha with total concentration and faith that the practitioner will be reborn in Amitabha’s Pure Land, a higher plane of existence in which it is much easier to attain enlightenment.

Very few collections of Buddhist art have been exhibited in Texas, Dr. Sano observed. “I particularly loved the Pure Land theme because the message is quite simple and the works of art are so beautiful,” she said, adding: “From the time I was a graduate student I was so impressed by the paintings and the sculptures that this religion inspired, so it’s just been a favorite topic of mine.” (San Antonio Express-News)

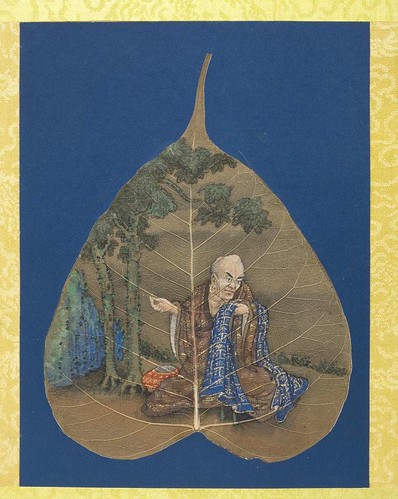

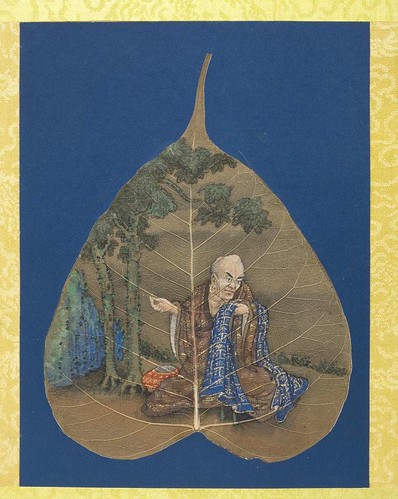

One of a series of Chinese Qing dynasty ink illustrations on

bodhi leaves depicting disciples of Shakyamuni Buddha. From

expressnews.com

Iconography of Amitabha Buddha can be difficult to distinguish from depictions of Shakyamuni Buddha as both are represented possessing the attributes of a Buddha without distinguishing marks. Amitabha images can often be identified by the mudra or ritual gestures depicted, such as the meditation mudra (with the hands brought together, palms upwards and thumbs touching), or the exposition mudra (right hand raised and facing outward, left hand downward with the thumb and forefinger touching). The earth-touching mudra (with the right hand directed downward over the right leg, palm inward) is used for seated depictions of Shakyamuni Buddha. Amitabha is often portrayed as accompanied by two bodhisattvas: Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), who appears on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left, although the order is reversed in some traditions of esoteric Buddhism.

To introduce the subject to visitors, the San Antonio Museum of Art exhibition includes works from across Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, the Gandhara region of South Asia, and Southeast Asia, demonstrating the endurance of Pure Land motifs down through history. The majority the exhibits are Japanese artifacts that depict how Amitabha descends to Earth from his Pure Land to greet dying souls, scenes of hell, and numerous divine beings that are on Earth to guide the faithful and assist in freeing those who have fallen into hell realms.

Bowing Buddha. Gilt wood sculpture from 17th–18th century

Japan. From expressnews.com