NEWS

The British Museum Reimagines Buddhist Shrine and Ancient Pilgrims with Smartphone Technology

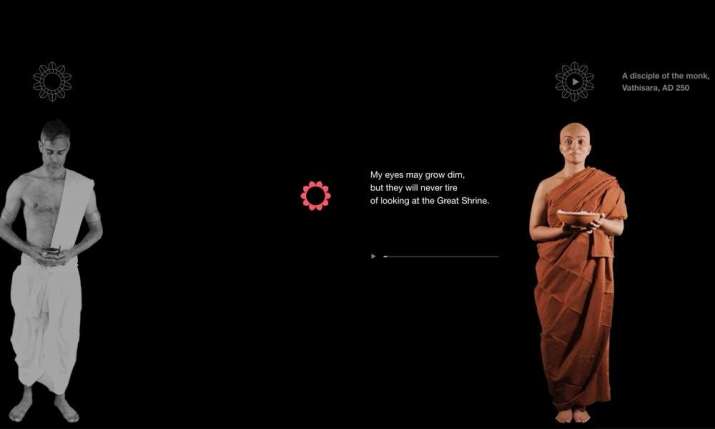

Part of the exhibit uses actors to render representations of pilgrims whose identities were left behind in inscriptions on statues at the Great Shrine of Amaravati. From theguardian.com

Part of the exhibit uses actors to render representations of pilgrims whose identities were left behind in inscriptions on statues at the Great Shrine of Amaravati. From theguardian.comThe British Museum in London is bringing smartphone technology to bear to bring one of the oldest and largest Buddhist monuments to life. The special exhibit, titled “Virtual Pilgrimage: Reimagining India’s Great Shrine of Amaravati,” features a double-sided relief from the ruined Great Shrine of Amaravati in southeast India and allows visitors to uncover the unique story behind the shrine’s significance by interacting with the financiers who funded its construction some 2,000 years ago.

The Great Shrine of Amaravati was one of the most important Buddhist sites in the world. Founded in the 2nd century BCE, near the city of Dharanikota in the state of Andhra Pradesh, the shrine flourished for almost a millennium, but fell into neglect in the 14th century and by the 18th century had become a stone quarry. Extensive excavations in the 19th century recovered the surviving carvings and statues, which are now on display in a number of museums across the world. With its collection of 120 carvings from the site (also known as the Amaravati Collection, or the Amaravati Marbles), the British Museum houses the largest collection of artifacts from the shrine outside of India.

The double-sided relief featured in the current display is a key part of these 120 artefacts. One side of the relief, probably carved in 250 CE, gives a glimpse of what the Amaravati Shine might have looked like in better days. It features a dome inscribed with Buddhist stories and symbols, guarded by two stone lions, which used to house a relic of an important monk or even the Buddha himself. In the center, an image of the Buddha stands at the gateway in human form, with devotees on either side. The other side features a much older relief, carved 300 years earlier in 50 BCE. On this side, pilgrims gather around a symbolic portrayal of the Buddha, who is represented as an empty throne under a Bodhi tree and a pair of footprints, perhaps a referral to his liberation from the confines of the human body.

According to Imma Ramos, curator of the museum’s South Asia collections, the two sides of the stone provide a unique glimpse into the history of the iconic representation of the Buddha: “The two sides of the stone also show us a fascinating development over the centuries in the portrayal of the Buddha, from a being whose power and authority can only be shown through a symbolic absence, to a real human figure depicted at the heart of the shrine.” (The Guardian)

Time has almost weathered away the inscriptions on the relief, but researchers have recently managed to translate Prakrit inscriptions written in Brahmi, dating from about 250 CE. The inscriptions record that the relief was donated to the shrine by a female disciple of the venerable monk Vathisara at the Great Shrine of Amaravati. Her name remains unknown, but to contribute the relief to the temple, she would have been a women of considerable means, despite being a female disciple of a monk, who would have commissioned the work to honor the Buddha and make merit for her family.

Over the centuries, pilgrims from different walks of life contributed to the construction and decoration of the Great Shrine. Often their identities were left behin, recorded as inscriptions carved onto the sculptures they donated. Researchers have identified several other donors of artifacts from the Amaravati Collection. In the “Virtual Pilgrimage” exhibit, the British Museum brings four of these donors to life. They are reimagined by actors and, with a tap on your smartphone, projected onto the walls. Using mobile phone technology developed in partnership with Google’s Creative Lab, visitors can use their smartphones to interact with the pilgrims and explore the carvings of the shrine in further detail.

As well as a female disciple, visitors can meet a 1st century BCE perfume maker called Hamgha who, together with his children, donated a carved pillar, a first-century CE Buddhist monk called Budhi who donated a “lion-seat,” a support for a pillar, together with his sister, Budha, who was a nun, and a woman called Kumala, who donated part of the elaborately carved railing that framed the shrine along with two other women called Sagha and Saghadasi, from the 2nd century CE.

Their stories “open up the gallery walls,” paint an image of the shrine in better days, and showcase the power of patronage in ancient India, as well as the historical and social significance of the shrine. (Engineering & Technology)

The exhibit Virtual Pilgrimage: reimagining India’s Great Shrine of Amaravati is free and runs at the British Museum until 8 October. The rest of the Amaravati Collection will be on display from November, when the Sir Joseph Hotung Gallery of China and South Asia and the Asahi Shimbun Gallery of Amaravati sculptures reopen after refurbishment.

See more:

British Museum ‘virtual pilgrimage’ reimagines Buddhist shrine (Engineering & Technology)

British Museum first to showcase interactive display with Wi-Fi link (The Guardian)

The Asahi Shimbun Displays: Virtual pilgrimage reimagining India’s Great Shrine of Amaravati (The British Museum)

The power of patronage at the Great Shrine of Amaravati (The British Museum Blog)

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global:

Buddhist Relics on Display in Andhra Pradesh’s Proposed New Capital Amaravati

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global: