FEATURES|THEMES|Books and Literature

Buddhism and Creative Writing, Part One

The exploration of the relationship between creative writing—especially poetry—and Dharma practice carries with it a multitude of questions. Can such writing be considered a part of our Buddhist practice? Is poetry always and necessarily a practice? Or is it always not so? And if only sometimes, based on what criteria? These are not easy questions to address, presenting a kind of koan in themselves.

Some schools of Buddhism may consider “art for art’s sake” to be improper and not really compatible with the Dharma life, viewing the whole enterprise as an expression of ego or self-indulgence. This subject can, however, be viewed from a number of angles.

It is self-evident that many writings that are full of Dharmic content also have aesthetic merit. These would include, in particular, many of the verse sections of both the Pali Canon and the Mahayana scriptures. When one reads the words of Brahma Sahampati, telling the newly enlightened Buddha that “there will be those with but little dust in their eyes who are wasting through not hearing the Dharma” and so forth, we are moved as much by the eloquence of those words as we are by the content of the message.

Again, the writings and songs of such great sages as Dōgen Zenji (1200–53) in the Zen tradition and Milarepa (c.1052–1135) of the Kagyu school of Vajrayana Buddhism persuade as much by their beauty as by their logic. In the visual arts, too, Buddhism has generated a great many stirring aesthetic offerings, from the thangka paintings of Tibetan Buddhism, to the Theravada murals of Thailand, to the Pure Land tapestries of Japan. It has often been seen fitting to clothe the Dharma in fine form. One might then say that this is acceptable as long as the message of the Dharma predominates, as long as the “art” is merely decoration. It seems a fitting form of worship to use the very best skills, the best colors, the best phrases, and so on, to glorify the Dharma, as long as it is the Dharma and not something else that is glorified.

The question then arises: where does Dharma end and non-Dharma take over? If we consider the verses of the Japanese master poet Saigyō Hōshi (1118–90), we find that there is a distinct Dharmic flavor, although few of his verses contain an explicit Dharma message. Rather, they express the experiences of a man living much of the time in retreat in the mountains, perhaps substantially for Dharmic reasons, but expressing all that arises in daily life.

Saigyō’s poetry revolutionized aesthetic appreciation in Japan at the time. For some people, the verses speak the language of Dharma. For others, the same verses demonstrate a refined aesthetic sensitivity and are valued primarily, or even solely, for that reason.

To take one of Saigyō’s poems more or less at random:

Sad, the haze in the meadow

where I pick young herbs

when I think

how it shrouds me

from the faraway past.

(Watson 1991, 24)

On the surface there is nothing overtly Dharmic about this verse, no explicit teaching and no Buddhist terminology. It is emotional; it contains imagery that evokes the life of someone living as a semi-hermit who is torn between the activities of his present existence and preoccupations from his past. It does not present a model of living in the here and now, nor of having one's mind set on nirvana. So, in a sense, we can say that this is a poem about mundane life. However, there is an atmosphere skillfully woven into the fabric of the poem by the author that enables immediate circumstance to speak of the wistful melancholy of life. It is about duhkha and about the author’s reflection on the human condition. The reference to being “shrouded” also brings the figure of Mara* into the picture. We behold a spiritual dilemma: is the “here and now” a refuge or a distraction from the real business of life? Is it a strength or a failing to ponder the “faraway past?” Is the poet right or mistaken to be “sad” that he is in retreat from the worldly affairs of human existence?

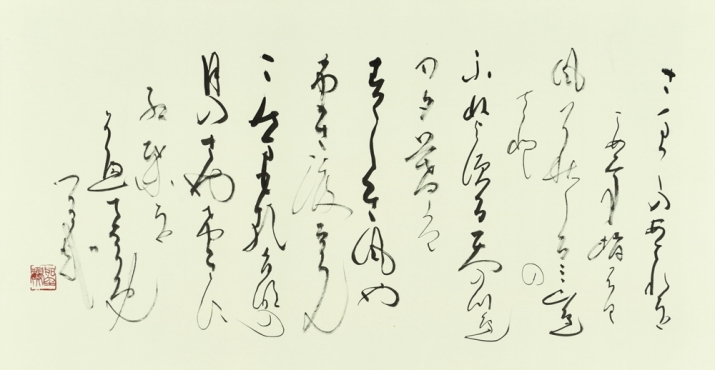

Saigyō Hōshi (1118–90) was a Japanese poet of the late Heian (794–1185) and early Kamakura (1185–1333) period. This is one of his most famous poems: If I may / I wish to die / under the cherry blossoms in spring / just around the full moon / in April. From art-annual.jp.

Saigyō Hōshi (1118–90) was a Japanese poet of the late Heian (794–1185) and early Kamakura (1185–1333) period. This is one of his most famous poems: If I may / I wish to die / under the cherry blossoms in spring / just around the full moon / in April. From art-annual.jp.Although Saigyō’s writing is not scripture, it can be argued that it encourages the reader do more spiritual work than many much longer passages of scripture or philosophy, and does so in an undeniably engaging way. The issue of whether literature and especially poetry is, as some posit, trivial or even immoral, or can be, as others maintain, seamlessly integrated with sincere Buddhist practice—being the examination, reflection, and penetration of real life—was an issue strongly contested in medieval Japan. In fact, Saigyō himself was sometimes caught up in these debates.

Was his poetry a “practice” or a distraction from practice? Even Saigyō was not always certain about this. But then, that very uncertainty could itself be considered an important spiritual challenge. Certainly, this issue raises significant questions about the nature of “practice” and its relation to aesthetics and creativity. I shall examine this question further in part two.

* Mara is the demon that tempted and harassed Shakyamuni Buddha as he sat in meditation beneath the Bodhi tree.

References

Watson, B. 1991. Saigyo: Poems of a Mountain Home. New York: Columbia University Press