FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Buddhism and the Martial Arts: A Conversation with Scott Park Phillips

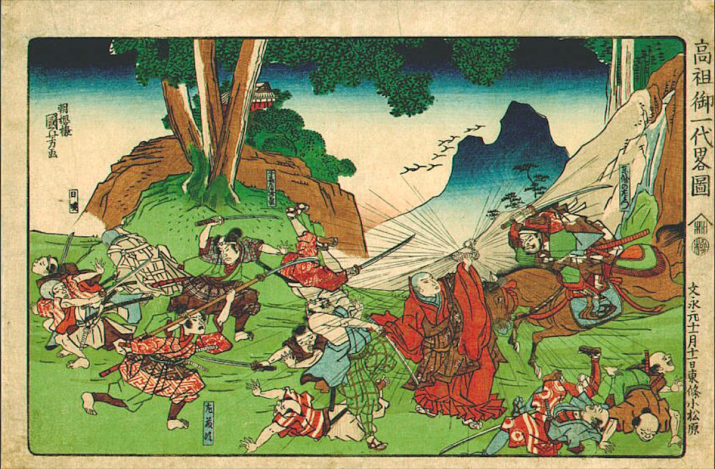

Nichiren using the power of his prayer beads to foil an attack by Tojo no Sayemon Komatsubara in 1264. Woodblock print, 1835, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Nichiren using the power of his prayer beads to foil an attack by Tojo no Sayemon Komatsubara in 1264. Woodblock print, 1835, by Utagawa KuniyoshiThe histories of Buddhism and the martial arts are intertwined to such a degree that a full understanding of either Buddhism or martial arts requires knowledge of the other. Mind control, the body as a vessel for spiritual practice, and the cultivation of transformed states of consciousness by which to execute skillful acts connect fundamental qualities of both Buddhism and martial arts. Both fields of study are vast with periods of murky history; both have traded in secrets. Lineages are established, contested, and invented, while modern nation states have tried to erase whole social histories that included intense fighting, to erase religion itself, as if there was never a time when martial skill, theater, and religious ritual overlapped and nourished each other. Tibetan monks disavow their bloody pasts with a modern emphasis on peace, while monks of Shaolin market their well-deserved renown and find a regulated way to continue to practice in modern China.

Historically, modern categories did not apply. Dance, ritual, fighting, sex, meditation, visualization, magic, and art were of a piece, connected in movement basics, ritualized practice, and philosophical cohesion. These elements were not learned and studied in isolation. In some ancient Buddhist contexts, dance means meditation; is meditation. Dance almost always indicated a transformation of mind connected to a deity: deities don’t walk. They dance.

A Shaolin monk in martial meditation headstand practice,

“Iron Skill.” Date and photographer unknown.

Image courtesy of Angry Baby Books

Pyrrhic dances were a part of military strategy; other dances were used to train militias. Ritual was often about exorcism, the pursuit and conquering of a demonic force. Inter-dimensional wrestling with parallel battles for victory in earthly and heavenly worlds was a basic concept of fighting. Nowhere is this more riotously depicted than in the fights of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King from the 16th century Chinese literary classic Journey to the West, derived from the true story of the Tang dynasty scholar Xuanzang traveling to India to obtain Buddhist scriptures. Hugely entertaining and elaborately described fights go on for pages and pages—under water, in mid-air. They fight with magic, with farm tools, with superhuman strength, and with strategic cunning. It is a story of eventual enlightenment, representing the unresolved elements of the human personality. They fight a lot; they fight anyone: human, divine, or demonic. It is comical and brutal. The poor Monkey King is a Buddhist seeker, never discouraged, but no fight is an easy one. The idea of the martial arts as some kind of health regimen and isolated sport is a 20th century invention.

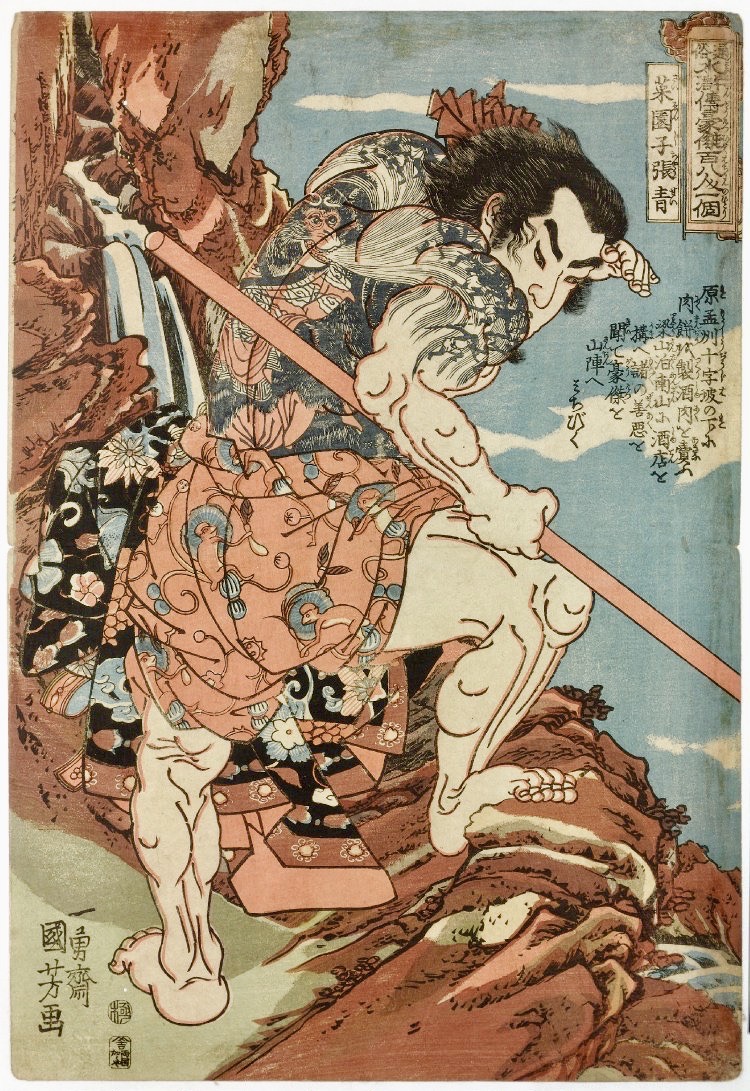

Saienshi Chosei (Zhang Qing, a Chinese warrior), barechested with

the Money King tattooed on his back, carrying a pole. c.1827–30,

Woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Described by legend as:

“a waist like a wolf, arms like an ape, a body like a tiger, and Sun

Wukong, the Money King tattooed on his back.” From 108 Heroes

of the Popular Water Margin. Image courtesy of the British Museum

More to the point, what would make for a better Chinese opera in the center of town than the exploits of the Monkey King? Elaborate fights by skillful martial artists. This is what made the Quentin Tarantino films Kill Bill: Volume 1 and Volume 2 (2003 and 2004) so entertaining and popular. “Kung fu” movies are an industry, just as Chinese opera has always parlayed intense fighting as entertainment. It is not hard to understand. Violence and humor join in the spiritual pilgrimage of Journey to the West.

Chinese opera actors, 19th century. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Angry Baby Books

Chinese opera actors, 19th century. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of Angry Baby BooksThis is all the more poignant, centered as it is on the staid and hapless Buddhist scholar Xuanzang seeking to discover texts in the Motherland of the Buddha. It is easy to see how fighting, performing opera, and the practice of monasticism fed off each other’s techniques and borrowed stories: the better the fight, the better the show. The Monkey King had martial invulnerability but he wanted the invulnerability of a bodhisattva and he would beat you to a pulp if you didn’t give him the scripture he asked for.

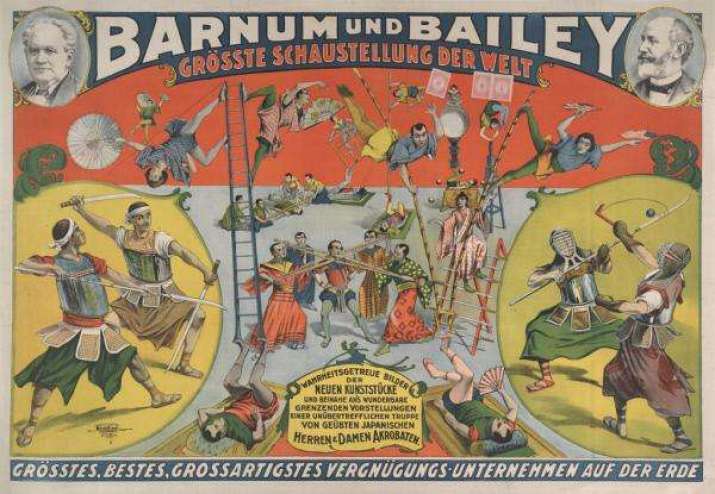

Turn-of-the-century circus poster, German tour of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. This American circus spectacular was comprised of Chinese martial artist entertainers. Artist unknown. Image courtesy of Joseph Svinth

Turn-of-the-century circus poster, German tour of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. This American circus spectacular was comprised of Chinese martial artist entertainers. Artist unknown. Image courtesy of Joseph SvinthScott Park Phillips is a martial arts anthropologist from a line of rabbis, social philosophers, and anthropologists. He is a “somatic historian,” using the body as the location and conclusion of history. Phillips is a talented martial artist familiar with many styles, their philosophies and histories, and a dancer trained in Western and Indian classical styles. He has a basic understanding of Chinese writing and speaking. Phillips has gained popularity as the author of two books that seek to correct modern notions of Chinese martial arts and suggest other scenarios of appreciation. Possible Origins: A Cultural History of Chinese Martial Arts, Theater and Religion (Angry Baby Books 2016) and its follow up Tai Chi, Baguazhang and the Golden Elixir: Internal Martial Arts Before the Boxer Uprising (Angry Baby Books 2019) make headway into the rich Chinese societal milieu that produced and sustained martial expertise as it was variously expressed in monasteries, Taoist temples, Chinese opera, and warfare. We can better see that in a society where kidnappings and throat-slittings were commonplace, the ubiquity of martial skill was a necessity. Martial arts were part of establishing and protecting order.

Books by Scott Park Phillips

Books by Scott Park PhillipsPhillips himself straddles the worlds of martial arts practice, scholarly writing for the Journal of Daoist Studies, and a YouTube channel featuring conversations with all sorts of important movement practitioners and historians. His books are a glory of clear writing, with ample annotations of everything from art to classical literature to online video content. As Socrates made clear in the Symposium, the best dancer is not always the best speaker. It is notable when an expert movement practitioner is also an historian and an author. In a crowded field of books about martial arts, Phillips’ writing stands out as a new model of research as well as making his own practice a type of living speculation.

Author Scott Park Phillips in the frog posture from the ancient system of

daoyin, an energetic and psychophysical form that dates to at least 200 BCE,

and is known to have been concurrently practiced in China by Buddhist

monks, opera performers, and martial artist warriors

Historically, one culmination occurred during the failed Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901), when a violent uprising of martial artists was denied its claims of invulnerability, defeated with the use of guns. Part of the defeat was a promulgation of the idea that their practices of strengthening the mind with the experience of emptiness, sometimes called the Golden Elixir, was superstitious, flawed, and fatal.

A modern copy of a remarkable performance poster for Buffalo Bill. This show was a re-enactment of the Chinese Boxer Uprising, an anti-foreign martial arts rebellion, subdued with the help of foreign nations and guns

A modern copy of a remarkable performance poster for Buffalo Bill. This show was a re-enactment of the Chinese Boxer Uprising, an anti-foreign martial arts rebellion, subdued with the help of foreign nations and gunsSince that time, Chinese governments have promoted a health-oriented version of the martial arts, something Phillips calls “the YMCA model.” In fact, the popularity of the YMCA in China significantly impacted the popular idea of martial arts. So did “kung fu” movies, in which some of the old ways survive as modern entertainment. Scott Park Phillips investigates the intersection of cultural behaviors, describing a complex environment in which Buddhism is always present, interacting with other realities of the time such as constant warfare and local fighting—and the presence of many orphaned children.

This amazing photograph from Europe during World War One shows Chinese laborers who worked for the Allied war effort in 1918. They stayed in camps set up by the YMCA. Two workers in this camp practice their Shaolin martial arts. These workers also brought their ritual robes and masks, and even performed simple versions of popular operas. Image courtesy of Angry Baby Books, copyright IWM

This amazing photograph from Europe during World War One shows Chinese laborers who worked for the Allied war effort in 1918. They stayed in camps set up by the YMCA. Two workers in this camp practice their Shaolin martial arts. These workers also brought their ritual robes and masks, and even performed simple versions of popular operas. Image courtesy of Angry Baby Books, copyright IWM“Let me paint a picture for you,” Phillips offered. “Buddhism. India. Let’s start with India. India had excellent martial arts but not as formal lineages, more as elements of ritual, games, dance, and sport. Where Buddhism spread, Indian cultures spread, and Indian fighting styles and concepts went along. The older caves at Dunhuang have fighters, sometimes as yakshas, which are derived from India. Basically martial art was of two types: within the tribe to discipline, train, or perform; and without the tribe for protection of family and land.”

This wonderful video of revived Indian Chhau dance shows the complete integration of theatrical, martial, and ritual aspects of a unique and ancient Indian form

Buddhism’s arrival with a universalist notion of culture is what inspired so many artists. At the same time, it cast martial arts in a different light, in a larger arena of deity action and supra-cultural unity. The multi-armed deities were armed with weapons. Wisdom was a sword. This assimilated well with the tradition of Chinese immortals, many of them former human generals and warriors. The pantheon of immortals in Chinese opera—itself once a ubiquitous theatrical expression at a local level—included anyone: Taoists, Buddhists, legendary characters, saints, divine creatures. (The Birthday of Guanyin Among the Immortal is a Cantonese opera masterpiece.) Hanuman the Indian monkey deity is none other than the Monkey King of Journey to the West. To this day in Varanasi, wrestlers vie all year long to be the victor and so portray Hanuman in the annual festival. Within Chinese Buddhism and Chinese opera, the Monkey King becomes a bodhisattva, kicking and screaming the whole way, mad at everybody, the star of the show.

Dharma protector Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, in The Monkey King Wreaks Havoc in Heaven. Qingdao Peking Opera Company, Manila, 2018. Image courtesy of What’s Happening PH

Dharma protector Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, in The Monkey King Wreaks Havoc in Heaven. Qingdao Peking Opera Company, Manila, 2018. Image courtesy of What’s Happening PHPhillips continued: “The Shaolin monastery was in fact a mini-state for centuries, with its own government and rites. It was a strategic military fact that whomever controlled the Shaolin Pass, controlled the area. Naturally, necessarily, the occupants of the mountain overseeing the whole landscape were the best fighters. Buddhism brought monasticism. So where it assimilated easily with certain Taoist practices like daoyin and sitting-and-forgetting, monasteries posed a new social structure with which to train adherents in ritual and fighting, but also, thanks to Buddhism, in the cultivation of mind and as a refuge for orphans, who were common in times of fighting. By the Song dynasty in the 11th century, Taoism and Buddhism were well integrated and even competitive.”

A page from the Daoyin Classic showing a seated overhead stretch

sometimes called “Holding Up the Heavens.” Date unknown.

Image courtesy of Wellcome Images

“These same boys who were trained in martial arts and Buddhist ritual practice did not always stay with the monastery. Work options were limited basically to being bodyguards, traveling opera performers, or being hired for a private militia. The traveling opera performers were experts in martial arts and the use of weapons. They were acrobatic and were required to portray a range of immortals and deities. Humorous plays included mocking monastic behavior and prohibitions, in a similar way to the mockery of monks in the Western Middle Ages. I call it a transgressive path of genuine practice. Theater and monastic rites were exorcistic. Theater was an expression of the orthodox indigenous religion of China.

“Chan Buddhism, or Zen, came from Taoism. Again, Buddhism added monasteries and a rigorous canon of texts, and in fact inspired Taoists to organize better their texts and adherents. Taoists have always performed martial and energetic arts. Daoyin, which I mentioned earlier, is a practice with archaic roots, combining breathing with stretching and pulling. I see it as separating your body from ‘your story.’ This way you can embody the absolute limit of wildness as well as the absolute limit of self-containment.

“I suspect that daoyin influenced the development of yoga in eras when Indian and Chinese Buddhist and basically Taoist practices integrated. Certainly, once Buddhist monasteries such as Shaolin were established, daoyin was practiced by monks at monasteries in teaching meditation practice; by opera performers for strength, agility, and fighting; and for Buddhist warriors who could understand that daoyin was the way to experience emptiness. Fighting is a Way. To be a Buddhist warrior meant, in part, to practice the Golden Elixir internal techniques.”

One diagrammed version of the Golden Elixir technique

for emptiness. Artist and date unknown. From Core of Culture.

“This emptiness is where Buddhism and martial arts really connect. In the practice of the Golden Elixir something alchemical in Taoist origin becomes an experience of emptiness and compassion, with the mental and breathing practices of Buddhist meditation connected to movement forms. In one of the Jataka Tales, the Buddha is King of Monkeys. In Journey to the West, the Monkey King practices daoyin and performs the Golden Elixir as he seeks Buddhist enlightenment by protecting the Chinese Buddhist scholar on his travels to India. In actual warfare between kingdom states in China, militias and armies brought both Taoist and Buddhist sorcerers to the battlefield. There is a deep integration of religion, practices of the mind, theater, and martial arts.”

With special thanks to Scott Park Philips for his kind help in preparing this article.

See more

Scott Park Phillips

Scott Park Phillips (academia.edu)

Scott Park Phillips (YouTube)

Core of Culture

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

World Peace! Thumbs Up! Some Martial Aspects of Buddhist Dance

The Metaphorical Sword

Body and Mind in Chinese Martial Arts: A Conversation with Xu Xiangdong

The Druk Amitabha Kung Fu Nuns: Combining Martial Arts and Meditation