I sat on a hardened cushion inhaling the vapor of burning incense in the main prayer hall of The Paramita International Buddhist Centre in Kadugannawa, a town in my home country of Sri Lanka. It was the full moon, or “Poya,” day, and it was raining outside. A solitary Buddhist monk was preparing for the evening chants before the white Buddha statue at the end of the hall. As he began to chant five minutes later I listened, appreciating the deep timbre of his voice emanating undisturbed in honor of the enlightened one.

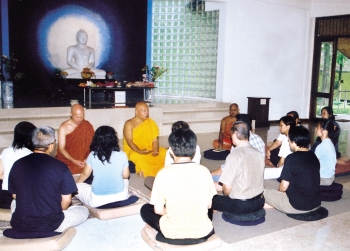

Poya day for me is a stressful one. My house lies in the vicinity of four Buddhist temples. As it happens, all four temples own amplified megaphone systems which bellow out Buddhist chants or sermons throughout the day. I often wonder what the Buddha would think of such commotion on the day on which he attained the mysterious nibbana. The day of Poya is associated with the observation of the precepts given by the Buddha, and is supposed to be spent in silent meditation and ritualistic activity; yet, the noise pollution created by the sound equipment forces me seek the silence of the international Buddhist center, where amplified Buddhism does not exist. There I chanted with the Buddhist monk while listening to the rain outside, which is something I have always enjoyed. My practice is simple. As well as chanting, it consists of occasional loving-kindness meditation and visiting temples of archeological value. I was born a Buddhist—yet I do not conform to some of the existing Buddhist conventions on this island. I believe that my way is correct, because Buddhism advocates seeking the truth alone.

Though I appreciate the principles of Buddhism as sound in order to better one’s life, circumstances have not allowed me to fully immerse myself in its practice. As a child, I was usually prevented from visiting temples by my father himself. Although he never explained why, with the contemporary escalation of crime and misconduct associated with the monks and the temples, I now see that he did it with my best interests at heart. Consequently, my practice also changed when I realized that I can categorically divide the sangha into two groups: the effective and the ineffective. In that respect, I try to keep myself on track by seeking out the “right” teachers of Dhamma and disassociating myself from those ineffective monks who would dishonor the name of the Buddha. I find my way is logically sound, as the Buddha himself discouraged blind faith.

Several months ago during the full moon, I sat instead at the ancient rock temple of Hindagala, where my first meditation master once lived. Venerable Mahinda was nearly 70 years old at the time, and it was he who taught me loving-kindness meditation and a few yogic postures to supplement it. In fact, he had been a millionaire timber merchant with no shortages in life, but on his 50th birthday had abandoned everything and become a monk. I found that exemplary, and saw every reason to respect and learn from him. By contrast, I find it disheartening to visit certain temples which abound in luxury and political power derived from favors done for the government. How do I honor a politician in a saffron-colored robe? Is his teacher really the Buddha, or does he follow the wishes of his political allies no matter how inconsistent the result of his action is with the Dharma? With the non-secular sector becoming proactive in the temporal world, are we heading towards anarchy in an ethical sense?

Statistics presented by the Police Department of Sri Lanka indicate that in 2011, a total of 1,871 incidents of rape were reported, 1,463 involving the rape of underage girls. Also very distressing is the fact that, according to Dr. Rasanjalee Hettiarachchi of the National Institute of Mental Health, roughly 10 Sri Lankans commit suicide each day. Sri Lanka is further listed among the five countries having the highest rates of alcoholism, and there has been a noticeable increase in corruption and misdemeanor associated with the temples. Having a background in psychology and counseling, I find that Buddhism’s potential in contributing to solve these serious social disorders is greatly ignored. The socio-political problems of contemporary Sri Lanka could be analyzed in the context of the following excerpt from the Cakkavaththi Sihanada Sutta, in which the Buddha with great fluidity and eloquence relates the reasons for the failure of law and order in a nation:

Thus, from the not giving of property to the needy, poverty became rife.

From the growth of poverty, the taking of what was not given increased.

From the increase in theft, the use of weapons increased.

From the increased use of weapons, the taking of life increased.

From the increased taking of life, lying increased.

From the increase in lying, the speaking ill of others increased,

sexual misconduct increased.*

It is apparent here that the Buddha saw and analyzed the origins of and reasons behind the escalation of contemporary crime over two thousand years ago. The Pali term akalika is often used in scriptures to indicate the applicability of the Buddha’s words to explain all incidents occurring in the past, present, and future. Buddhism has many effective methods to resolve the social problems that exist in societies like Sri Lanka. Yet instead, I see the society and government moving away from the teaching of Buddhism due to the misdemeanors of both politicians and some members of the sangha. I believe that such an exodus from faith will eventually prove to be counterproductive for the propagation of Buddhism in the entire world. This will be very unfortunate, as the problem lies not within the philosophy but with the mismanagement of Buddhism as a resource for human development.

*Based on a translation in http://www.basicbuddhism.org/index.cfm?GPID=29

References