FEATURES|COLUMNS|Bodhisattva 4.0

Buddhist Spiritual Care

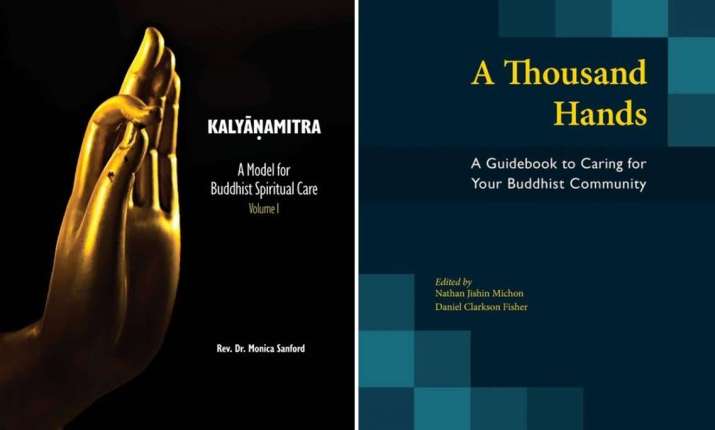

Book covers for Kalyāṇamitra: A Model for Buddhist Spiritual Care, Volume 1 by Rev. Dr. Monica Sanford and A Thousand Hands: A Guidebook to Caring for Your Buddhist Community, edited by Nathan Jishin Michon and Daniel Clarkson Fisher. Images from sumeru-books.com

Book covers for Kalyāṇamitra: A Model for Buddhist Spiritual Care, Volume 1 by Rev. Dr. Monica Sanford and A Thousand Hands: A Guidebook to Caring for Your Buddhist Community, edited by Nathan Jishin Michon and Daniel Clarkson Fisher. Images from sumeru-books.comBuddhist spiritual care is a growing aspect of Dharma leadership. In this conversation, Buddhistdoor Global spoke with two Buddhist chaplains about how the field is changing. Rev. Dr. Monica Sanford is one of only a handful of fully trained Buddhist “practical theologians” producing scholarly research on the profession of Buddhist chaplaincy today, and is one of only two Buddhists to lead a religious life program at a North American college or university. Rev. Dr. Nathan Jishin Michon is a Shingon Buddhist priest and a minister with the Unity-and-Diversity World Council.

Buddhistdoor Global: How do you see ordination or lay status as they relate to being a chaplain?

Nathan Michon: It partly depends on the type of tradition one comes from and one’s own feelings about where they are in life. It can also depend on the type of chaplaincy someone is going into. For example, serving in military chaplaincy can more clearly go against certain monastic precepts, whereas one can do it as a lay upasaka/upasika. However, there is nothing against ordination as a chaplain, especially in training.

Monica Sanford: Chaplaincy is a profession with a particular skillset focused on pastoral care, interreligious and cultural competency, and the spiritual formation of the chaplain. I find that most training for Buddhist monks, nuns, priests, ministers, and Dharma teachers does not fully convey the first two competencies. Even if one is already ordained with a strong spiritual formation, they are still likely to need additional training to become a competent chaplain. Training as a chaplain will also deepen their spiritual formation through interreligious engagement.

BDG: How do Western Buddhist views of spiritual care differ from those of Asian Buddhists? How are they similar?

NM: On the whole, I think they are fairly similar. Modern Asian spiritual care is largely modeled after Western spiritual care, so many of the principles are the same, such as an emphasis on deep listening, seeking to understand patient needs, and avoiding proselytization. Rather than a strict Western/Eastern divide, however, I think we can find more differences in the character of Buddhist spiritual care between nations. We should also keep in mind that views about spiritual care are partly reliant on local cultural and legal norms.

MS: This is a question we are still seeking to answer. I believe the answer is rooted in cultural understandings of what constitutes “care” and “spiritual care.” Chaplains accompany those who are in moments of crisis that would preclude forms or “normal” functioning—hospitalization, imprisonment, military service in a combat zone, emergency response, bereavement, and so on. External events such as these can precipitate spiritual crises. The chaplain provides spiritual support during these periods so that the spiritual aspects of the crisis can be navigated in ways that draw on one’s spiritual and religious resources for support and lead to spiritual growth.

BDG: The use of self is one of the benchmarks by which neophyte chaplains are evaluated in their CPE training. Yet the role of a pastoral caregiver demands the abandonment of self for the benefit of the patient or client. Since Buddhism negates the idea of a self, is there some special advantage a Buddhist approach can offer here?

NM: Of course it still depends on people’s individual dispositions and conditions, but I do think there are a few advantages that Buddhists have from this perspective. Philosophically, most dedicated Buddhists (as chaplains would be) have wrestled extensively with ideas of no-self—maybe for years or decades. In many Buddhist traditions, there are also practices that help one to feel/ experience/embody those notions of no-self. Conversely, however, the notions of selfhood can be so different between Buddhism and the culturally dominant Christianity that it can also require far more effort from a Buddhist to convey their perspectives in CPE training. So, there can be both advantages and disadvantages.

MS: Absolutely. The first thing to remember is that the standards for CPE training were not written by Buddhists or for Buddhists, really. Despite this, even Buddhists must make skillful use of self, including abandoning the self when appropriate. Buddhist chaplains practice both upaya and prajñā in this way. Use of self in the mundane sense is upaya. We are the tool we carry into the room, an embodied human presence with a certain amount of professional training and personal experience. We draw on both to empathize with patients, understand them, assess their needs, and act accordingly.

At other times, the best and most effective care comes from a place of selflessness, at the level of prajñā or direct insight. Chaplains report that these moments feel effortless because they are no longer wasting energy protecting their ego, they are connecting with the patient at a level beyond the duality of self and other, and responding to suffering in a way that catalyzes spiritual growth through nonattachment.

BDG: The pandemic has transformed our awareness of the fragility of life, our interbeing, and our relationships with old and young. In offering spiritual care to frontline healthcare workers, what do you see and how to you respond?

NM: An already challenging environment became all the more so. And the lack of break to catch one’s breath and process everything can build up and be very difficult. Of course, listening to individual needs is critical, as well as making sure that people feel their basic needs are being met. It’s impossible to provide decent care to others if you do not feel that you yourself have solid ground on which to stand.

I think that one very important thing for anyone in the caring professions to understand, whether or not in times of crisis, is the difference between empathic distress and empathic concern. These represent two rather different mindsets and ways of approaching one’s job that can have very different long-term results. Empathic distress refers to taking on someone else’s pain as you interact with them. It’s not uncommon but that will build up over time and lead to burnout more often than not. Empathic concern, on the other hand, refers more to the wish for another’s condition to improve. We can try to understand someone, be with them, and carry that compassionate wish that someone’s pain and stress will go away without embodying that pain for ourselves.

BDG: When we think of Buddhist teachers, we typically see them inside the sangharama. In the best of all possible worlds, how would you explain to them the value of chaplaincy in a diverse, interfaith service setting?

MS: Chaplaincy takes everything that we learn from the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha and puts it to work in the world to reduce suffering. It is the direct application of the Buddha’s teaching. The Dharma was expounded all the better for having been questioned by people of other traditions; many critical concepts were clarified in conversation with brahmins and ascetics of other orders. Likewise, as Buddhist chaplains, our wisdom is clarified through direct engagement with suffering as experienced by those different from ourselves. Through this engagement, we will also make the world a better place and strengthen the causes and conditions that allow the sangha to thrive.

I also believe that Buddhism has something unique to offer the profession of chaplaincy that is sorely needed right now—a way to provide spiritual care to the growing number of non-religious people—40 per cent of young adults according to some surveys.

Since God/gods are not essential to the spiritual path in Buddhism—Tibetan deity yoga notwithstanding—we have a blueprint for spiritual growth and flourishing that may be exactly what those who have “lost faith” need right now. Humans don’t stop having spiritual needs or existential questions when they stop believing in God or participating in organized religion. What they sometimes lose is a framework for understanding and making meaning from their experiences. We can help them reframe conversations and ideas about meaning and values without reliance on theistic language.

BDG: What’s the hardest lesson you’ve had to learn in offering spiritual care as a Buddhist?

NM: Although it can be challenging, remaining observant and “on” or ready in the chaplaincy mode while in the chaplaincy setting is important for me.

MS: Try not to let your self get in the way. That is, don’t let your need to be helpful interfere with actually being who and what the other person needs right now. Ultimately, this can be done best through those experiences of selflessness when self-other duality dissolves. But let’s be real, that’s not every time. Sometimes, we get those beautiful moments when the ego dissolves on its own and sometimes we have to squash it with a mental boot. And sometimes we fail. In fact, we fail a lot. We say the wrong thing and do the wrong thing. But humans and human relationships are resilient and can often recover.

BDG: What’s the greatest joy you’ve experienced in offering spiritual care as a Buddhist?

NM: I think the greatest joy is more of a “Dharma joy” or contemplative joy than an emotive type of joy, so being able to connect with a patient on a deeper level as if the hearts are connected in a deep sense of shared mutual peace, that to me feels like a pinnacle of Buddhist spiritual care.

MS: Most of the time, we’re just witnesses to other people putting in the hard work of coping with their own suffering and seeing to their own spiritual growth. That’s beautiful. That’s what keeps me going back to the work again and again. I learn from the witnessing. I see the buddha-nature in others—countless Buddhist and non-Buddhist others—and I really believe, for a second, I have that buddha-nature, too. I lean into that when I’m being present with them, not because I’m special or something, but because they have shown me the way more deeply and more often than any teacher at the front of the Dharma hall ever has, more vividly than any sutra, more perfectly than any Dharma talk. It’s a kind of living kōan, the living Dharma alive in each person.

BDG: How do you see the relationship between spiritual care and engaged Buddhism?

NM: Engaged Buddhism can take many shapes and forms. Buddhist spiritual care is simply one of those forms.

MS: Spiritual care is engaged Buddhism. Spiritual care is Right Livelihood. So are lots of other professions—activists, farmers, and teachers can all practice engaged Buddhism and Right Livelihood. So can chaplains, in our way. The way you choose is the one best suited to your skills and temperament.

Within the field of spiritual care, a new sector is emerging called “movement chaplaincy.” This is an area in which chaplains focus on caring for activists involved in social justice movements, such as by working for non-profits, attending protests, and supporting those most harmed by injustice. This would naturally include a lot of the work engaged Buddhism has done recently. I am not currently aware of any Buddhist movement chaplains, but this may be an area in which Buddhist chaplains who want to do more in relation to social justice could be of benefit.

Editor's Note: A previous version of this article attributed Nathan Michon's responses to Monica Sanford and vice versa.

See more

Kalyāṇamitra: A Model for Buddhist Spiritual Care, Volume 1 (Sumeru Books)

A Thousand Hands: A Guidebook to Caring for Your Buddhist Community (Sumeru Books)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

A Buddhist Chaplain for the Tibetan Community in Toronto

Toward a Multi-faith Vision of University Chaplaincy in America: An Interview with Reverend Greg McGonigle

Life in America as a Chinese Buddhist Monastic: An Interview with Venerable Guan Zhen

Buddhist Ministry Initiative Conference: Building Partnerships and Forging Ties

Buddhist Explorations in Pastoral Care and Contemplative Counseling

Related news reports from Buddhistdoor Global

Columbia University Hosts Buddhist Chaplaincy Conference in New York

First Buddhist Chaplain in the US Air Force Reflects on His Service

Sakyadhita to Host 15th International Conference at The University of Hong Kong

Multifaith Chaplaincy Proposed by The Fire Fighters Charity in the UK