FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Dance at Dunhuang: Part Three - The Sogdian Whirl

Sogdian merchant. China, Tang dynasty, 7th/8th century,

terracotta. Image courtesy Musée Cernuschi, copyright

Stephane Piera. Musée Cernuschi, Paris

Sogdian merchants were the leading tradesmen working the Silk Road. Sogdiana was a kingdom-state, of which the legendary city Samarakand was the symbolic and cultural center, and would have been located in areas of today’s Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. Known for their cunning and business sense as well as their hardiness and skill in serving nomadic and trading cultures, the Sogdians provided traders, entertainers, religious teachers, and craftsmen to a bustling Silk Road commerce.

They were also famous for dancing. The dance they performed has been described as a whirlwind with a swirling technique, characterized by impressive full body turns. In the exhibition catalogue The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith (London, 2004), Dunhuang scholar Susan Whitfield named it “The Sogdian Whirl.”

Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks, Bezeklik

Thousand Buddha Caves, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

Late 8th century, mural painting. From en.wikipedia.org

The Sogdian Whirl accompanied Buddhism as it moved along the Silk Road. It even became a meme in Buddhist art, reflecting the attitudes that inspired a plurality of cultural expression within a new philosophy. Northwest China, in which Dunhuang was an outpost, was from the 4th through the 6th century controlled by competing, essentially nomadic cultures that gradually adopted Chinese ways of life and systems of government. The Sogdian Whirl as depicted in Buddhist cave art demonstrates this evolution and Sinicization, and reached the sophistication of Tang dynasty (618–907) Buddhist culture and beyond.

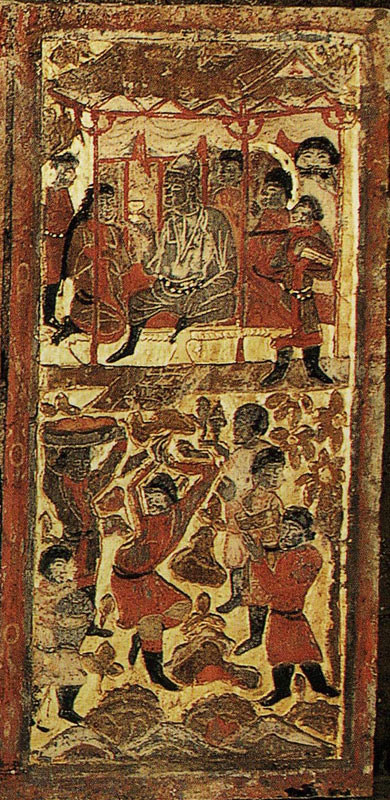

People of the Silk Road, Mogao Caves, Dunhuang. Tang

dynasty (618–907), mural painting. Image Public Domain

There was no single metropolitan court style, as with the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), until the Tang dynasty. In the north, a comity of oasis kingdoms participated in complex, multifaceted dialogues between regional traditions and the foreign influences arriving with Buddhism.* Dunhuang, the site of the painted caves of the Mogao Grottoes, today epitomizes what was a great Buddhist civilization of scholars, monks, artists, and political leaders interweaving the cultures between and including Persia and China. Symbols of power and erudition, even conquest, dances were exchanged like everything else. Dances were shape-shifting mirrors of the time.

Male Sogdian dancer performing the Sogdian Whirl. China,

Tang dynasty (618–907), cast bronze. Image courtesy of

Shandan Municipal Museum, Gansu Province, China

Sogdiana was primarily Zoroastrian, and some depictions of Sogdians show fire rituals ablaze. Many Sogdians became Buddhist over time, and their dances were immortalized by Buddhist painters and sculptors—cave artists—whose work spread throughout the entire Silk Road regions, including Samarkand. As the artworks illustrated here show, the Sogdian Whirl became an element of Buddhist devotional practice, as well as a staple of the Tang court dance repertory.

Tomb panel of funerary bed for Sogdian tradesman An Qie,

Xi’an, showing dancer performing the Sogdian Whirl. China,

Northern Zhou dynasty, 579, granite. From safarmer.com

Tomb panel of funerary bed for Sogdian tradesman An Qie, Xi’an,

showing Sogdian trader performing the Sogdian Whirl. China, Northern

Zhou dynasty, 579. From amazon.com

Funerary bed of Sogdian tradesman An Qie showing panel with Sogdian Whirl on the right. China, Northern Zhou dynasty, 579. From transoxiana.org

Funerary bed of Sogdian tradesman An Qie showing panel with Sogdian Whirl on the right. China, Northern Zhou dynasty, 579. From transoxiana.orgBuddhist cave art along the Silk Road had a variety of functions. As a reflection of its patrons, it was meant to impress. There were complex narrative paintings serving as historical and spiritual records for illiterate people, transcending the many languages spoken. Activity that would take place in the caves is often depicted: making offerings, teaching, music, and dance. Dance is lavishly recorded in the Mogao Grottoes, and other Buddhist caves in China and Silk Road sites.

Sogdian dancer in preparatory step, excavated from the

tomb of Kudihuiluo, Shouyang County, Shanxi Province.

China, Northern Qi dynasty (550–77). From Wang

Kefen, image courtesy Jiang Dong

Sometimes a depicted dance is part of a narrative painting or sculptural array. It is descriptive, with elements of the dance being precisely described. At other times, depicted dance is prescriptive, mnemonic, instructing a viewer how to do the dance, or telling us what about it should be remembered.

Dance can be encoded with political, religious, territorial, and choreographic information. It is not always easy to discern the encoding of ancient dance depictions; its symbolic value is easier to see. China has a long tradition of prescriptive movement depictions included among other learned treasures of science, philosophy, and leadership.

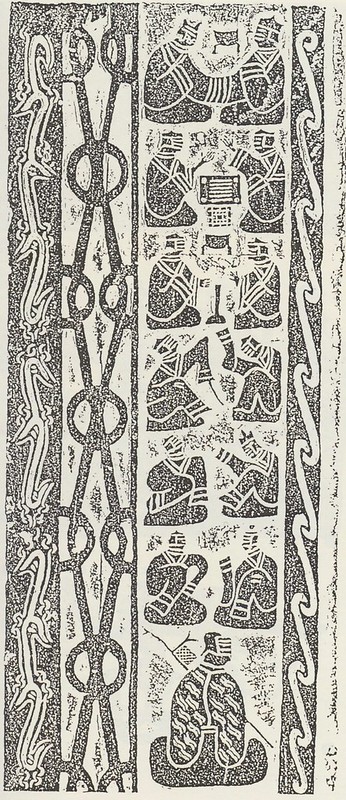

Relief demonstrating dance sequences of a ritualized

social dance called Shu, which was held at banquets

and often integrated dances from different cultures.

China, Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), stone. After

Wang Kefen, Chinese Dance: An Illustrated History,

Beijing Dance Research Institute, 2000, image 130

Relief work showing Sogdian dance movements in progression. China, Tang dynasty (618–907), brick. After Wang Kefen, Chinese Dance: An Illustrated History, Beijing Dance Research Institute, 2000, image 233

Relief work showing Sogdian dance movements in progression. China, Tang dynasty (618–907), brick. After Wang Kefen, Chinese Dance: An Illustrated History, Beijing Dance Research Institute, 2000, image 233The Sogdian Whirl, usually performed on a small, circular felt carpet, was a rage, a genuine dance craze in a period when dance was robust and the exchange of cultural concepts was a primary action of the Buddhist epoch. Dancers move intuitively and are naturally skilled at non-verbal communication. It is natural how groups of dancers working for patrons and traders, as well as the aristocrats and traders themselves, would spread a popular dance.

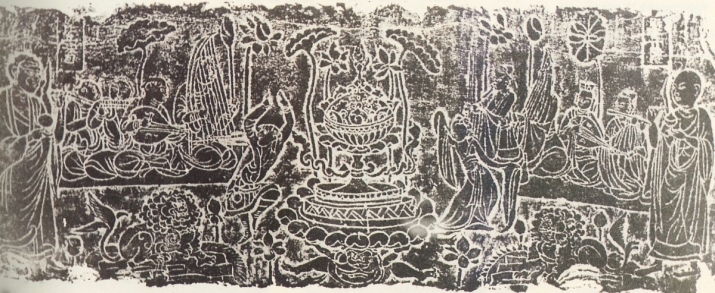

Panel from the funerary couch of a Sogdian merchant depicting

a banquet, with dancer performing the Sogdian Whirl. China,

Sui dynasty (581–618), marble. Image courtesy Miho

Museum, Japan

Dance embodies the zeitgeist. It symbolizes a deeper, fuller reality than that contained in words. Dance was an actualization—an extension of the living ideas that stimulated spiritual understanding, philosophical exploration, and harmonious cultural plurality.

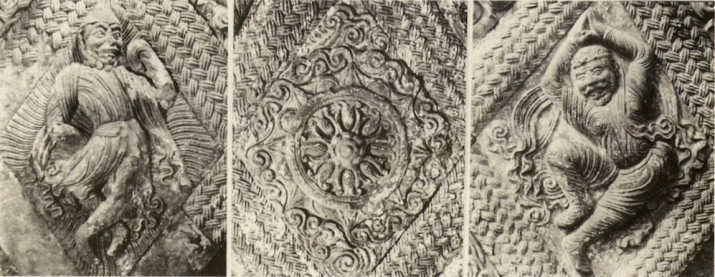

Carvings excavated at Yangchi, Ningxia, showing the Sogdian Whirl being

adapted to Chinese norms. China, Tang dynasty (618–907), stone. After

Wang Kefen, Chinese Dance: An Illustrated History, Beijing Dance Research

Institute, 2000, image 232

Heavenly devas dancing on small carpets like the early Silk Road dancers, showing the Sogdian Whirl fully appropriated into the high style of Tang dance and art—the dance is refined into technical precision and Chinese silk billows with a light touch; Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang. Tang dynasty (618–907), mural painting. After Wang Kefen, Chinese Dance: An Illustrated History, Beijing Dance Research Institute, 2000, image 517

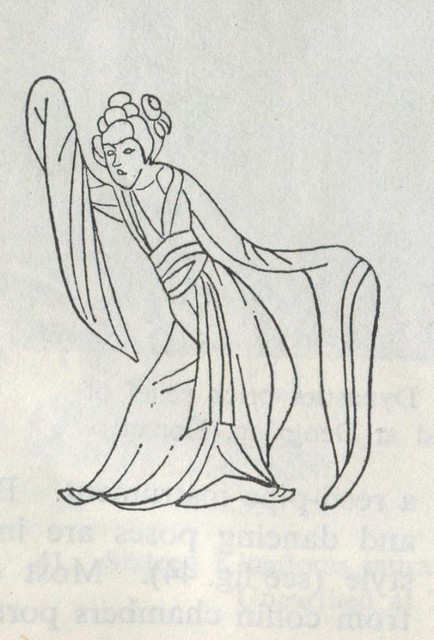

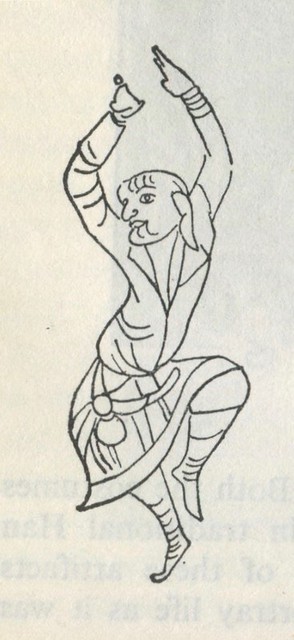

Heavenly devas dancing on small carpets like the early Silk Road dancers, showing the Sogdian Whirl fully appropriated into the high style of Tang dance and art—the dance is refined into technical precision and Chinese silk billows with a light touch; Mogao Cave 220, Dunhuang. Tang dynasty (618–907), mural painting. After Wang Kefen, Chinese Dance: An Illustrated History, Beijing Dance Research Institute, 2000, image 517Nowhere better is the seed of this emergent epochal realization depicted than in the sweet scene of two dancers carved into the plinth of a 5th–6th century Buddha. Dancing around a large ritual brazier, a woman with Han Chinese costume and hairstyle is performing a characteristically Han dance. Her partner in the dance is a man, dressed in Sogdian costume and performing the Sogdian Whirl. It is entirely plausible that dances still performed today have elements that can be traced to the Sogdian Whirl.

Panel for plinth for a Buddha, Xingping County, Xi’an, depicting a Buddhist ritual with monks, a lotus-censer, and Han and Sogdian dancers. China, Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589). After Wang Kefen, The History of Chinese Dance, Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1985, p. 46

Panel for plinth for a Buddha, Xingping County, Xi’an, depicting a Buddhist ritual with monks, a lotus-censer, and Han and Sogdian dancers. China, Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589). After Wang Kefen, The History of Chinese Dance, Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1985, p. 46

Han female dancer, possibly performing the pose “Flag Blowing in the

Breeze,” from the plinth for a Buddha. Northern and Southern

Dynasties (420–589), line drawing. After Wang Kefen, The History of

Chinese Dance, Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1985, p. 46

The Sogdian Whirl was a dance connecting civilizations. The rise and influence of the Sogdian Whirl calls to mind these words by Lama Anagarika Govinda:

“The Buddha’s teachings were not only meant for the 6th century B.C. – though they were put into the language of his time and his country – but they conveyed a universal meaning, beyond caste, creed or race, and expressed the laws of a timeless reality. This reality has to be rediscovered from generation to generation, from century to century – nay, from one civilization to another, and every single individual has to realize it by his own experience in the depths of his own being” (Lama Govinda 1976, 5).

Sogdian male dancer performing the Sogdian

Whirl, from the plinth for a Buddha. Northern

and Southern Dynasties (420–589), line

drawing. After Wang Kefen, The History of

Chinese Dance, Foreign Languages Press,

Beijing, 1985, p. 46

References

Lama Govinda. 1976. Creative Meditation and Multi-Dimensional Consciousness. Wheaton, IL: The Theosophical Publishing House.

* This thought is paraphrased from Annette Juliano, “Chinese Pictorial Space at the Cultural Crossroads.” http://www.transoxiana.org/Eran/Articles/juliano.html

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Dance at Dunhuang: Part One

Dance at Dunhuang: Part Two – The Case for the Feitian