FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

Early Transmission of Sanskrit Buddhist Texts in China: An Interview with Prof. Shashi Bala, Part Two

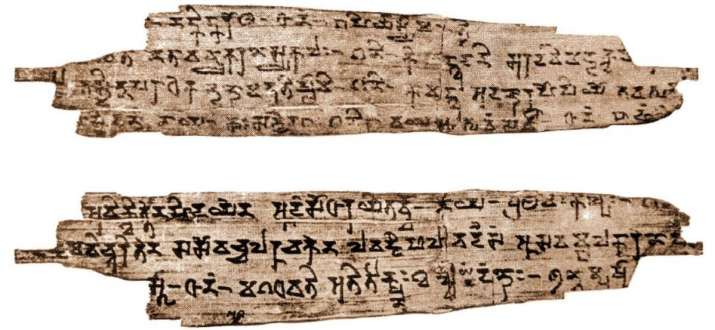

Fragments of the oldest manuscript of the drama Shariputraprakarana by Ashvagosha from the Kushana period, second century CE, discovered in Kizil in the Turfan area of Central Asia. Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi Bala

Fragments of the oldest manuscript of the drama Shariputraprakarana by Ashvagosha from the Kushana period, second century CE, discovered in Kizil in the Turfan area of Central Asia. Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi BalaContinuing our conversation with the eminent Indian scholar Prof. Dr. Shashi Bala, specialist in Buddhist art and crosscultural connections among Asian countries, about the ancient Buddhist links between India and China. In the second part of this interview with the dean of the Center of Indology at the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan in New Delhi, we discuss the transmission of Sanskrit Buddhist texts to China and their impact.

Buddhistdoor Global: What was the impact of Sanskrit Buddhist scriptures on Chinese culture?

Prof. Shashi Bala: The impact of Sanskrit scriptures on Chinese culture was far reaching, it is quite deep and it all went through the translation of Buddhist texts. The period when the Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese can be said to be the most glorious chapter in the history of cultural exchange between India and China. There are around 3,000 texts in the Chinese Tripitaka, which is a huge amount of Buddhist scriptures encompassing an extensive body of knowledge about Indian culture and civilization. It covers the humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, philosophy, literature, linguistics, arts, medicine, geography, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, physical education, and more. The Buddhist canon is not merely a compendium of religious texts, it consists of both secular and sacred sciences. It is a boundless treasure encompassing whatever knowledge was available to the ancient Indian Buddhists, it all illustrates and interprets the doctrine of the Buddha and also later developments. Buddhist scriptures represent a synthesis of the achievements of Indian civilization and cultural developments at certain historical periods. Therefore, it introduced a new culture—that of ancient India—to China.

Prof. Shashi Bala visiting Crescent Moon Lake in Xinjiang, China. Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi Bala

Prof. Shashi Bala visiting Crescent Moon Lake in Xinjiang, China. Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi BalaIn the beginning of the transmission of Buddhist knowledge to China, monks and scholars began working on very simple texts, such as the Jatakas, the texts of the Buddha’s lives, some narratives related to the Buddha, and some historical legends. For example, they were much fascinated by the miracle of Shravasti. Another category of influential texts that reached China was the Avadanas, a division of Buddhist texts related to the lives of the monks and lay disciples of Shakyamuni Buddha. Normally the Avadanas are used to help people easily understand the doctrine of the Buddha.

BDG: What are some of the Sanskrit Buddhist texts that played a key role in transmitting Buddhist knowledge from India to China?

PSB: There are a few Buddhist sutras that are very important and gained popularity in China, such as the Vimalakirti Nirdesha Sutra, the Saddharma Pundarika Sutra (Lotus Sutra), the Prajnaparamita Sutras (Perfection of Wisdom Sutras), the Sukhavativyuha Sutra (Pure Land Sutra), and the Amitabha Sutra. Many of these sutras, translated into Chinese, are chanted by Buddhists throughout East Asia to the present day. These texts have incredibly strong roots in the cultures of East Asia and continue to show vitality, not only as translations transmitting the glorious message of the Buddha, but also as great works of philosophy and literature.

The Prajnaparamita Sutras became very popular in China. They address the unreality of all phenomena and the concept of shunyata (emptiness). The concepts of prajna (the wisdom that penetrates the essential nature of all things) and paramita (perfection or reaching the other shore of enlightenment, which is the opposite of delusion) was something new for the Chinese. So many versions and translations of these sutras were made over the centuries, which shows how much people were interested in them. There were also many commentaries written by scholars. One such commentary was written by the great Indian monk and translator Kumarajiva (344–409). These sutras had a profound impact on Chinese Buddhist philosophical thought.

The Vajracchedika Prajnaparamita Sutra is also among the texts that had a great impact on Chinese culture. The name of the text often is translated as a the Diamond Cutter Sutra, but Vajracchedika does not mean “diamond cutter.” Buddhist sutras are such profound philosophical texts and cannot be translated like this.

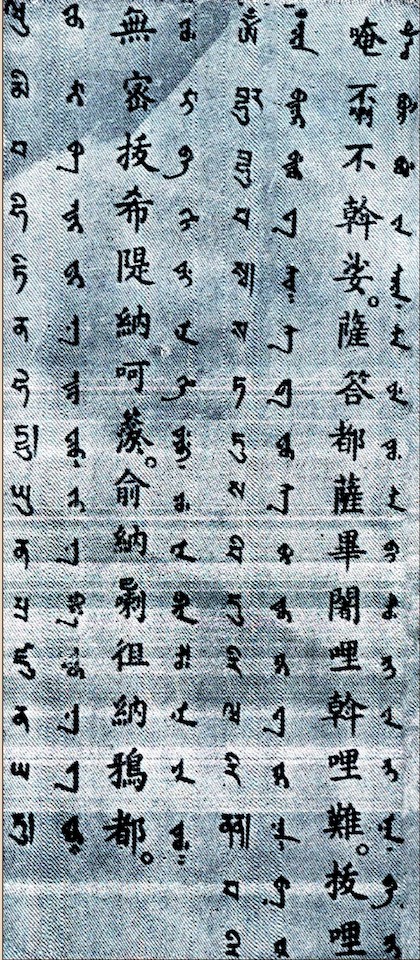

Gayatri mantra from Manchuria, Ragu Vira archives.

Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi Bala

BDG: What was the place of the sutras in monastic discipline in the early transmission of Buddhist texts?

PSB: The sutras on the Vinaya, the rules of monastic discipline, were also very important because monasteries were set up and the Chinese were looking for rules for monks and nuns. So, they translated the Vinaya sutras and this also impacted the lives of emperors and of laypeople. When Buddhism reached China, the monastic rules were not adequate and the lack of the Vinaya inspired them to translate the texts on monastic discipline, which allowed them to establish guidelines for monastic life, confer monastic names to monks and nuns, teaching them how to preach the Dharma and methods for expounding the sutras and performing different types of ceremonies.

BDG: How did early Buddhist texts related to the practice of meditation influence Chinese cultural life?

PSB: The Chinese were fascinated by dhyana, the practice of meditation, which was something new for them. In dhyana, one focuses the mind on one point in order to purify the soul, thereby eradicating one’s illusions and perceiving the real truth.

Dhyana was widely practiced in India before the time of the Buddha. He adopted the concept of dhyana and it was later incorporated into Buddhism. The texts on breathing exercises for good health also became popular among the Chinese in the early years of transmission. When the Chinese first encountered the translations of the Indian Buddhist monk, they saw that the texts have rich and elaborate imagary. It was a new mode of thinking for them. They were immediately fascinated and finally they were conquered by the Buddhist philosophy.

When Bodhidharma (c. fifth to sixth century) reached China from Kanchipuram in India, there was a new wave of practicing meditation, seeking enlightenment, and studying martial arts. He was not in favor of studying sutras. Gradually this developed into the Chan school of Buddhism and its headquarters were established at the Shaolin Monastery. The philosophy of Chan Buddhism soon became very popular and influenced particular styles of arts, including painting. There are many Chan monasteries and masters in China, and Chan meditation centers have been established in many countries. From China it was carried to Japan, where it became Zen, and also to Korea, where it became Seon. The Dhyana Sutras are a great contribution of Buddhism that has had a great impact—not only on cultural life, but also on social development in East Asia.

Prof. Shashi Bala at the Great Wall of China. Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi Bala

Prof. Shashi Bala at the Great Wall of China. Image courtesy of Prof. Shashi BalaRelated features from Buddhistdoor Global

Echoes of Indian Buddhist Culture in China: An Interview with Prof. Shashi Bala, Part One

The Chan (Zen) Connection between China and Tibet: A Conversation with Sam van Schaik

Lingyan Monastery: The Development of an Ancient Monastery in Contemporary China