FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Everyone with a Cow Owes Me a Favor – Dancing, Healing, and Spiritual Realization, Part One

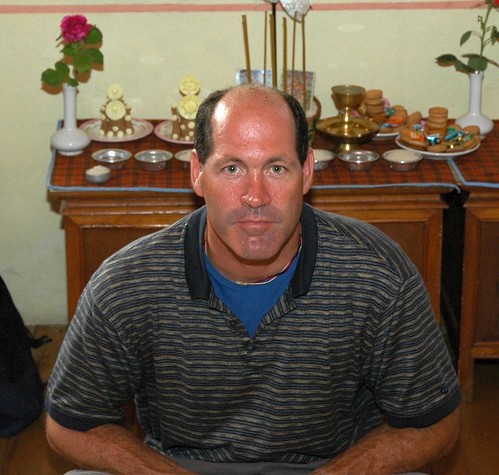

Mike Borre in Bhutan, after meeting the Nizer Tulku, 2006.

Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of Culture

Twelve years ago, as part of Core of Culture’s dance research and documentation of ritual dances in the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, we brought with us Mike Borre, a 45-year-old American man, to meet six traditional healers over the course of a month. Several of these healers used dance, or were connected with ancient dance lineages. More generally, there is a movement continuum between dance, martial arts, meditation, massage, sound, and healing—whether a two-man Ayruvedic massage rippling non-stop from wrist to ankle, or the conferring of power from a reincarnated master of an ancient lineage of visionary dances, movement is a means of transformation. Healing processes use movement as a gateway to other dimensions of the self where change can occur.

Mike suffered from early-onset Parkinson’s disease, which he been dealing with for six years using modern Western medical treatments, including drugs, surgeries, and even brain implants. It appeared all the more devastating because Mike was a strapping, muscular athlete: a nationally ranked swimmer in his heyday, an outdoorsman, and father of three lively children.

Mike agreed to be our “test subject” with the traditional healers. Just as Core of Culture considers cultural analysis inaccurate if it does not include dance, we also consider a survey of Bhutan’s dances incomplete without studying the movement-inclusive healing arts, which appear in Buddhist, Bon, Aryurvedic, and shamanic practices. We could not have imagined the spiritual dimensions to be uncovered, or the physical and psychological transformations that would occur in Mike.

In some kind of parallel way, these traditional healers behaved in a manner we had experienced with masters throughout the Himalaya regarding sexuality and sexual behavior: illness was simply part of the human experience, something to be understood and used along with the body-as-vehicle, as a means of greater understanding, but never something to be stigmatized, over-emphasized, made taboo, or out of the ordinary. Illness is a normal thing in its way.

This series of articles is the first time I have published anything about Mike’s extraordinary healing encounters in Bhutan. At the time, Core of Culture was in the middle of a five-year survey and documentation of ritual and monastic dance, and we did not want the sensational aspects of Mike’s journey to overshadow the years of unprecedented dance research, of which it was a part. Also, because illness and healing are among the most intensely personal experiences one can have, we did not want to violate Mike’s own process, and he was in the throes if it. I took thorough and precise notes, as I do on all fieldwork expeditions. These notes, and the photographs by my colleague Gerard Houghton, inform me now.

Mike died as a passenger in a car accident 10 years ago, struck by an out-of-control driver crossing lanes on an icy highway. Renewed contact with a mutual friend and the realization of this 10-year anniversary prompted me to begin writing these pieces. Mike is missed by many in Michigan, where he is from, and in Bhutan, where he was embraced as one of their own. His life has been a lesson that the spiritual dimensions of life can be astonishing and unpredictable.

My job in the process of bringing Mike to traditional healers was simply to take account of the healers’ actions and, primarily, to observe Mike during these encounters, as well as before and after. It was not, and never is, my duty to determine if such-and-such a reincarnated master is really reincarnated, or whether a diagnosis—such as Mike received several times: that his illness was due to offending a particular deity during his teenage years—had any merit. My job was to observe. My task now is simply to share.

I shall begin with the most extraordinary encounter as it sets the stage from which to present the others. As was the case in all our privileged work in Bhutan, although we were given historical access and liberties, we were not always allowed to photograph or film, and in some cases, not allowed even to make notes. The sanctity and very special circumstances of this account meant no photography of any kind. I was permitted to make notes afterwards.

Bhutan, land of healing, 2006. Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of Culture

Bhutan, land of healing, 2006. Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of CultureThe patriarch of all monks in Bhutan, a pope of sorts, is called the Je Khenpo. A highly realized master, lineage holder in Drukpa Kagyu and Nyingma traditions, the Je Khenpo is the spiritual leader of Bhutan, guiding the spiritual destiny of the kingdom. During our time working there, the 69th Je Khenpo held this position. The 68th Je Khenpo had died, and the 67th Je Khenpo was dying, in his final days.

We had been keen to meet the 67th Je Khenpo, known as the Nizer Tulku, because he was the reincarnation of the dance-revealing treasure revealer Woogpa Lingpa, whose tradition at that time was down to a mere five performers. Core of Culture worked closely with the living traditions of other treasure revealers who left dances, Pema Lingpa, Dorje Lingpa, and Karma Lingpa among them. We had also helped revive traditions and steered them away from extinction. We were keen to meet the Nizer Tulku to hear him speak and to document his dances.

We were stunned, however, when we learned that he was also the reincarnation of a high tantric master, a healer of trembling diseases, whose name we never learned even when we were told he arrived in Bhutan riding a ray of light. Many of our highest-placed contacts lamented the fact that it was virtually certain Mike could not meet the one healer with the most power to heal him. The dying Nizer Tulku had royal bodyguards protecting him from any and all visitors and no one was allowed to see him, being served by a 24-hour nurse, fed intravenously, and in a deep state of yogic meditation.

We’d had such luck until this, I tried everything I knew, contacted every source I could imagine, and still was not successful arranging a meeting. One day, caught up in this effort, our production assistant, Longchula Dorji, entered my office and said with some authority:

“Sir, I helped introduce artificial cattle insemination in Bhutan.”

“Dorji, that’s great,” I answered. “But we are busy here trying to do something for Mike.”

“But sir,” he protested. “It’s true. I really did help introduce artificial cattle insemination in Bhutan!”

“Dorji! Why are you bothering me with this right now?”

“Sir, everyone with a cow owes me a favor. The Je Khenpo Nizer Tulku is staying with his niece. His niece would have no cows if it weren’t for me. I am sure I can arrange a meeting for Mike to meet the Nizer Tulku.

Sure enough, despite all supplicants being denied for several years, Dorji arranged a most rare audience with the Nizer Tulku, royal bodyguards notwithstanding, or rather, standing down. After we were greeted by the nurse and the niece, it took more than an hour for the Nizer Tulku to be readied. He was coughing, moaning, and crying out from the adjacent altar throne room where he lay, something difficult to hear. Finally we were led into his chamber.

We beheld a very fragile, partly reclined skeleton of a man, legs folded in the lotus position. His eyes were urgent resulting in a penetrating focus of ever-more-grand intensity. He had a scraggly mustache and white beard. Colored string, to be tied around our necks, had been laid out on his forearm. He wore a ceremonial robe and hat, and carried a scepter-like silver tube containing mantra scriptures. His lower half was covered with a green blanket.

When Mike entered, the Nizer Tulku straightened taller, and the most extraordinary vortex of energy, emanating behind him in a widening funnel shape, pervaded the room. He suddenly appeared towering and powerful. At same time, it looked like he was only barely here in this world and the skeleton of a man was a mere chrysalis; the real Nizer Tulku a raging power of light and energy. It was holy. Mike stood humbly, hands folded in front. The Nizer Tulku began to recite a mantra, and called each of the four of us forward so he could bonk us on the head with the silver scepter. As he continued his mantra, his voice took on an unusual timbre. He gazed at Mike. Mike looked to him.

Then Mike began to shake head to toe in a wild fashion. He was a big, muscular man. It was shocking and took up a lot of room. He never fell down, always stayed upright, but arms, legs, feet, hands, head, eyes, flew about making this lifelong athlete look like a ragdoll in a tornado, like he was being struck by lightening. It was terrifying in a way, but not frightening to any of us, who remained calm despite the floor and walls and platforms of this old country house rocking like it was about to crumble. This shaking lasted about five minutes. When it was over, a relaxed Nizer Tulku tied strings around our necks and we backed away reverentially, making our exit. As we did, Mike turned to me and asked, “Why was the room shaking?”

“The room was shaking, Mike, because you were shaking” I told him.

“No I wasn’t,” he replied. “I was looking at the Je Khenpo, we were together in this really mellow meditation.”

I didn’t answer. Mike’s Parkinson’s palsy stopped after that. He shut off the pacemaker connecting his heart to his brain, designed to stimulate dopamine production, and never turned it on again. He never took Parkinson’s drugs again. His eyes took on a sheen I had never seen and his face was transformed.

As we left the house, the Je Khenpo’s niece told Dorji, “That always happens to the ones who get healed.” She waved to him as we headed down the path. “Thanks for the cows!”

Two days later we were working in a remote village conducting dance research and an excited, joyful man came running toward us: “Did you hear?! Did you hear?”

We asked him what was the wonderful news. “The 67th Je Khenpo has died!”

I thought to myself, “Holy Jesus, we killed your pope. We’re all going to jail.” But before I could say anything, I learned something about Bhutan and its spiritual leaders. What all believed was that the Je Khenpo, the great Nizer Tulku, who had suffered so much, was waiting to meet Mike, whom they truly believed was someone very special. Our trip was never the same after that, and neither was Mike.

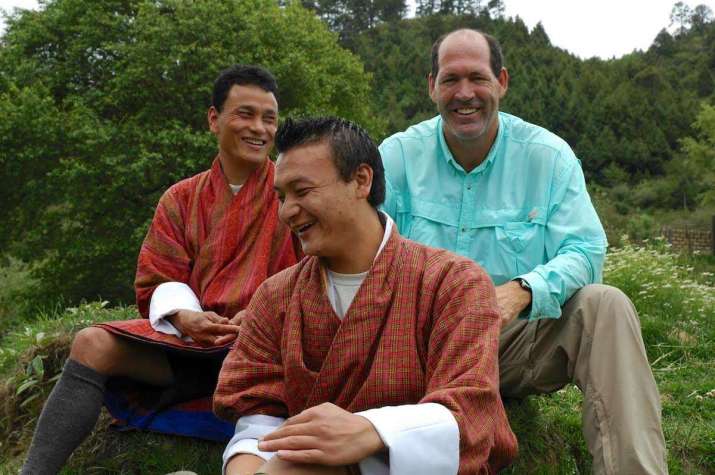

Longchula Dorji, his son Pema, and Mike enjoying Bhutan, 2006. Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of Culture

Longchula Dorji, his son Pema, and Mike enjoying Bhutan, 2006. Photo by Gerard Houghton. From Core of CultureThis article is dedicated to the memory of Mike Borre.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Ritual Readying – Dancing, Healing and Spiritual Realization, Part Two

Empowered Mantra – Dancing, Healing and Spiritual Realization, Part Three

Pawo Dorji, Mountain Oracle of King Gesar – Dancing, Healing, and Spiritual Realization, Part Four

Dancing, Healing, and Spiritual Realization, Part Five: Epilogue