FEATURES|THEMES|Philosophy and Buddhist Studies

Fascinating and Auspicious Buddhist Devices: Nianfoji

This article was originally published in Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that article.

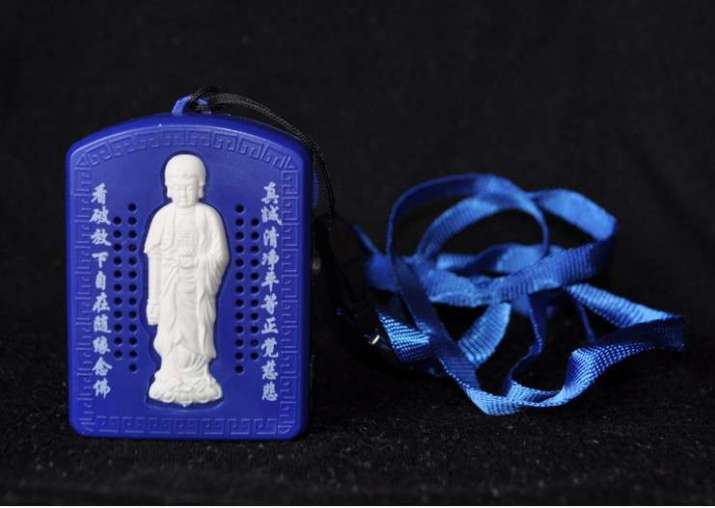

The Buddhist trade fair opened on 11 May 2019 in the city of Xiamen, China, one of many that are organized here throughout the year. Our mission in visiting the fair was to find new and interesting gadgets that play recordings of Buddhist chants, sutras, dhāraṇīs, and mantras. My interest in these electronic devices, known as nianfoji (念佛机), began in the Zhongnan Mountains in 2008, when Master Juecun, abbot of one of the Buddhist temples in this mountainous region at the time, gave me a small, blue, plastic box, with a figure of Amitabha Buddha in the middle and two phrases engraved on either side.

Despite being so small, one could listen at a surprisingly high volume to five versions of the repetition of the mantra Namo Amituofo. The pilgrim could hang this nianfoji around his neck and listen to the mantras while climbing the mountain. I was quite fascinated by the aesthetic and sound of these little devices and wanted to find out more about their origin, the value they have to devotees, and the different designs. Over the years, I began collecting one here and one there when I came across them at Buddhist temples and Chinese shops. I noticed that several of them played recitations of the Pure Land Buddhist teacher Master Jing Kong (b. 1927; also known as Master Chin Kung), who is renowned for being one of the first Chinese monks to use technology to spread the Buddhist teachings.

In one of his teachings on YouTube, the master speaks of the importance of leaving the nianfoji on 24 hours a day, since even if we cannot hear them at night because we are asleep, hungry ghosts can. Master Jing Kong claims that many hungry ghosts want to be released from their state and hope to reach the Pure Land: “If we leave the nianfoji turned on 24 hours a day, then we will help those who are in the Youmingjie [underworld]. The ghosts are also your protectors and there are many inside your house. If you don’t let them listen to the recitations, they will forget to recite to the Buddha.”*

Nianfoji for pilgrims. Image courtesy of the author

Nianfoji for pilgrims. Image courtesy of the authorDespite their attraction as religious objects, I was surprised at the almost complete lack of research surrounding nianfoji. A study by Natasha Heller (2014) stands out among the handful conducted. After analyzing the nianfoji, she mentions the way in which, despite being mechanical chanting, the devices emulate the sacred sounds that are spontaneously emitted in the setting of Western Paradise, where Pure Land Buddhists aspire to be reborn.

We know that chants and recitations have played an essential role in the spread and popularization of Buddhism in China. The first fanbai (Skt: bhasa or “recitation of scripture”) were from the period of the Three Kingdoms (220–80 CE) and the Northern and Southern dynasties (386–589 CE). Throughout the period of Chinese dynasties, the fanbai would be the most widely renowned sacred chants in the ecclesiastical and lay worlds of Buddhism. (Chen 2005) Over the course of China’s history, there were a series of reformulations and developments in Buddhist chants, especially in the period of the Republic of China (1912–49) and once again during the economic opening of the 1980s. Faced with the need to modernize the country, Buddhists began to disseminate doctrines via different mediums: journals, CDs, videos, and even religious karaoke. (Ríos 2017) And from among this diversity of media, these little sound gadgets started to spread, which at first only played a limited number of chants and recitations. However, today we can find an astonishing assortment of nianfoji that contain hundreds of recordings, recitations of complete sutras, and a wide range of designs featuring Buddhist symbols such as the lotus flower and the Pure Land triad: Amitabha Buddha with two bodhisattvas: Guanyin (Avalokiteshvara) and Dashizhi (Mahasthamaprapta)—boxes of various sizes with different motifs, small altars, buddhas, bodhisattvas, and a slew of other designs, with high-level sound and advanced digital technology.

Nianfoji at a Buddhist fair in Xiamen, 2019. Image courtesy of the author

Nianfoji at a Buddhist fair in Xiamen, 2019. Image courtesy of the authorAlthough Heller points out that these devices are not intedned to replace individual recitation, one of the intentions of Chinese Buddhist recitation is to gain merit or a real and effective response from the Buddha. The nianfoji do help to create a suitable spiritual environment, but more importantly, the experiences that Buddhist devotees recount of their nianfoji would seem to stimulate the Buddha, and they often receive miraculous responses and, thus, merit.

In this regard, we not only find the interpretation of Master Jing Kong and the possibility of liberating hungry ghosts with the recitations issuing forth from the devices, but there are also diverse examples of devotees who experience ganying by leaving their nianfoji turned on. Ganying is a mode of spontaneous response that occurs naturally in a universe holistically conceived in terms of patterns and interdependent order. Resonance is the mechanism by which categorically related albeit spatially distant phenomena interact. The concept of ganying in Chinese Buddhist interpretations takes on a doctrinal and soteriological value that is palpable in the thousands of tales of devotees who experience ganying with buddhas and bodhisattvas. In Buddhism, the principle of ganying was used to explain celestial omens, moral retribution, ritual efficacy, natural and astronomical cycles, political upheavals, and so on. (Sharf 2002)

Some of these examples refer to a person who dreamed of non-Buddhist family members by chanting Amituofo (Amitabha Buddha) and, upon awaking, realized that he had left the nianfoji turned on the entire night. This same person said that when he turned on the device, animals came to his home to listen to the recitations from the device. (Ríos 2017) Other stories of a more auspicious nature recount, for example, the sad life of a woman who was beaten by her drunk husband. One day she found Buddhism and obtained a nianfoji that she left on the entire day in the house. Since then, her spouse stopped drinking, no longer beat her, and helped their son to do his homework.**

Nianfoji. Image courtesy of the author

Nianfoji. Image courtesy of the authorIn another story from 2015, a group of secular devotees decided to visit a woman living in misery in a rural area. The woman had a 28-year-old son and a 32-year-old daughter who both had mental illnesses. The son lived somewhere else, isolated, because he was occasionally violent. The daughter lived with her mother and, after a relationship turned sour, she became mentally ill. The woman had not gotten out of bed for nine years. The devotees brought a nianfoji with them as a gift when they visited and also left them money. That same afternoon, the mother left the nianfoji turned on. On the third day, the daughter unexpectedly got out of bed and recovered.

As you can see, these little gadgets would seem to have acquired real power among Chinese devotees that suggests empathetic resonance or ganying with the Buddha, stimulating his healing power and compassion through the recitations and resulting in an auspicious response.

With the aim of highlighting their value as religious material culture and as objects of power in Chinese Buddhism, I decided to keep a small collection of nianfoji and to continue enquiring into their use and the stories told about these devices. With the support of Top China Grants from Banco Santander at the Catholic University of Chile (UC), Prof. Hugo Palmarola at the Design School and Fondecyt Research Funds (No. 3190076), we started a project that consisted of compiling a collection of nianfoji and then hosting an exhibition.

That is how we ended up attending the Xiamen fair, as well as visiting several Taobao webpages selling nianfoji and scores of Buddhist shops in China. We managed to collect 50 devices for the exhibition, which would have been held in Santiago de Chile in 2020, but was postponed due to the pandemic. However, we have made a video in which we share a small sampling of nianfoji, and we explain them on Buddhistdoor en Español. As noted in the video, the wide range of designs and aesthetics have continued to evolve over the years, and with the onset of new technologies, the quality in recent models has risen significantly.

Although smartphones and Buddhist apps integrating the functions of nianfoji have gradually replaced these devices, and many older models may now be discontinued, new designs are still being created and promoted online, fascinating everyone who enjoys unusual curios whose sacred chants may well reach the ears of the Buddha.

María Elvira Ríos (b. 1980) is a doctor in Asian and African studies, specializing in China, from the Centre of Asian and African Studies at El Colegio de México (2015). She is a member of ALADAA CHILE (Latin American Association of Asia and Africa). Her publications address subjects related to contemporary Chinese Buddhism and Chinese culture and language. Her studies have been published in numerous academic journals. She currently teaches the course Buddhist Aesthetics at the Institute of Aesthetics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and is a Fondecyt postdoctoral fellow (3190076) at the same institution, where her dissertation is entitled “The ecological reflection of Chinese Buddhism”.

* 淨空老法師法語:現在有念佛機很好 (YouTube)

** 不可思议!家中播放念佛机,竟然……. (yidianzixun.com)

References

Chen, Pi-yen. 2005. “Buddhist Chant, Devotional Song, and Commercial Popular Music: From Ritual to Rock Mantra”, Ethnomusicology 49.2 (2005): pp. 266–86.

Heller, Natasha. 2014. “Buddha in a Box: The Materiality of Recitation in Contemporary Chinese Buddhism”, Material Religion, Vol. 10, pp. 294–315.

Ríos, María Elvira. 2016. “Nuevos medios religiosos chinos: el Nianfo-ji, en Corro, Pablo; Robles Constanza y Ayala, Matías”, Estética, medios masivos y subjetividades, Santiago: Instituto de Estética, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Sharf, Robert. 2002. Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Amitabha’s Vow-Power: The Augmentative Cause that Bestows Splendid Merit and Real Benefits

What is Attained through Amitabha-Recitation?

Chanting in Concord

The Tibetan “Songs of Realization”

The Bodhi Group: Singing in Praise of the Buddha

The Sound of Awakening: Meeting the Mongolian Yogini Kunze Chimed