FEATURES|THEMES|Film

Film Review: Walk with Me – A Welcome Break from Stressful City Life

Thich Nhat Hanh walking meditation. Photo courtesy of UA CineHub

Thich Nhat Hanh walking meditation. Photo courtesy of UA CineHubWalk With Me premiered on 1 September in Hong Kong. Being present at the premiere, Buddhistdoor Global had a chance to interview one of the directors, Max Pugh, and one of the monks featured in the film, Brother Phap Huu. Public screenings will be held from 21 September–8 October at UA Cinemas (UA Cine Times, UA Cine Moko, UA iSQUARE) in Hong Kong, for screening dates outside of Hong Kong, please refer to the website for Walk With Me.

Walk With Me is a cinematic and meditative journey into the lives of the brothers and sisters of the Plum Village monastic community. Filmed over the course of three years, the film provides a unique glimpse into life lived at a snail’s pace at the remote monastery in southwestern France founded by Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh (Thay).

The film can be seen as a scrapbook of scenes from the monks and nuns daily lives—we see them preparing meals, shaving heads, welcoming pilgrims, attending lectures by Thich Nhat Hanh, and sitting for meditation—interspersed with snippets of the monastics on tour in the US, and breathtaking stills of nature. The filmmakers purposely show both the good and the bad sides of monastic life, and the occasional yawn or admission of boredom by the monks in the film are endearing and serve as a reminder that they are, like the film’s viewers, just human. As Brother Phap Huu—the yawing monk—comments: “Being a monastic and putting on a robe, you are automatically thought to be a super monk. But there is a development that we go through as monks and as humans. I know many young people can relate to this, you fidget and you yawn. It took me many years before I found inner peace.”

The snippets of monastic life are occasionally framed by the baritone voice of Benedict Cumberbatch, reading from Fragrant Palm Leaves, a collection of Nhat Hanh’s early writings. When approached for the role of narrator, Benedict Cumberbatch apparently agreed immediately, stating that he had read Thich Nhat Hanh’s books and had been reading up on meditation for his role in the recent Marvel blockbuster Doctor Strange. Although the narration offers little explanation, the quotes are inspiring and the inclusion of Benedict Cumberbatch in the film, opened doors to new audiences.

Nun chanting in a bell tower, Plum Village France. Photo courtesy of UA CineHub

Nun chanting in a bell tower, Plum Village France. Photo courtesy of UA CineHubAll in all, the film feels like a meditative exercise that carries a certain calm and joy. However, according to Max Pugh, one of the directors, this is not what the directors or the monastics had originally intended for the film to be.

It was Max’s brother, Brother Phap Linh (a monk at Plum Village), and Brother Phap Huu who came up with the idea of making a film about Plum Village. Grasping the opportunity to be closer to his brother’s new life and to potentially document his transition into monkhood, Max jumped at the opportunity to make a film in Plum Village.

Hailing from what Max described as a Western documentary tradition or a European art house film tradition, Max and Marc J. Francis went through several screenplays for the film, from a documentation of Brother Phap Linh’s transition into monkhood, to a film about Thich Nhat Hanh, and even a “road or rock band movie” but “with no sex and no drugs” of the monastics on tour in the United States. Both Brother Phap Linh and Thich Nhat Hanh, however, refused to be the star of the production as it ran counter to their practice, and eventually the directors left those ideas behind.

“After a few months of development, it became clear that we had to make a film about almost 1,000 monastics all over the world,” said Max. “But filming the stories of so many monks is basically impossible, so we developed an approach where we basically just received the present moment through the camera. And in the editing Marc and I became conduits of this present moment to the screen.”

Filmmakers Marc J Francis, left, and Max Pugh, right on location at the Plum Village Monastery in France. Photo by Anne-Sophie Mauffre. Image courtesy of UA CineHub

Filmmakers Marc J Francis, left, and Max Pugh, right on location at the Plum Village Monastery in France. Photo by Anne-Sophie Mauffre. Image courtesy of UA CineHubPerhaps in part due to this process, the film can at times make one feel a little lost, especially if one is seeking a clear framework or storyline. The film seems to feature four monastics, but we are given no narrative on their role in the film. Max mentioned that inevitably these monastics stick in our memory more than others because they appear in more or longer shots, but that they were never structured as the main characters in the film. Despite all the loose segments of film, as a whole, the documentary does have a certain flow.

The monastics of Plum Village are especially close to the seasons, which determine their daily schedule: the monastics go on rains retreat during winter, open their doors for visitors in the summer, and head out on tour in the autumn. As the seasons frame monastic life, so do they frame the film: “Nature gave us an organizing principle for the film,” Max explained. “But to make the film that way, we had to throw out the idea of placing one scene in front of the next, or that one scene was filmed in America and one in France. It was all interconnected. The audience can forget where they are or where they think they are and just go with the flow of the seasons.”

Although one can recognize the flow of the seasons, the film offers little more to guide viewer’s experience. The stillness of the film might be relatable to those with meditative experience, knowledge of mindfulness, or those who been on a retreat, but for the novices among us, the film might be cutting a bit short on information on Plum Village and its practices. Watching it might feel as if one can see the surface of a pond but we fail to breach the surface to be immersed in its depths.

Brother Phap Huu, however, is hopeful that the film might inspire even those without previous meditation or mindfulness experience to go out and explore more: “Not everyone will go to a Buddhist monastery to experience a retreat. It is just outside of their comfort zone. So this film is acting as an indirect helping hand to bring the experience to cities where people may have a little interest but they don’t want to go to a temple. They can go to a theater and they can watch a screen and enjoy themselves. I believe that if they are interested, the film will touch something deep inside of them. It is kind of an invitation, as in the title. Part one is watching the film, part two is for you to go out and explore more.”

“Thich Nhat Hanh had the aspiration to turn movie theaters into meditation halls and creatively that is what we wanted to do.” Max adds. “Thay loves movies, and getting to the movie theater was always a dream of his. He gets to people through books, through Dharma talks, and the Internet. The movie theater was a logical next step. . . . So if the audience can leave the crazy city behind and just sit and allow the film to take them away into a meditation for 94 minutes and they walk out and they feel different, happy, clear, I could not feel happier.”

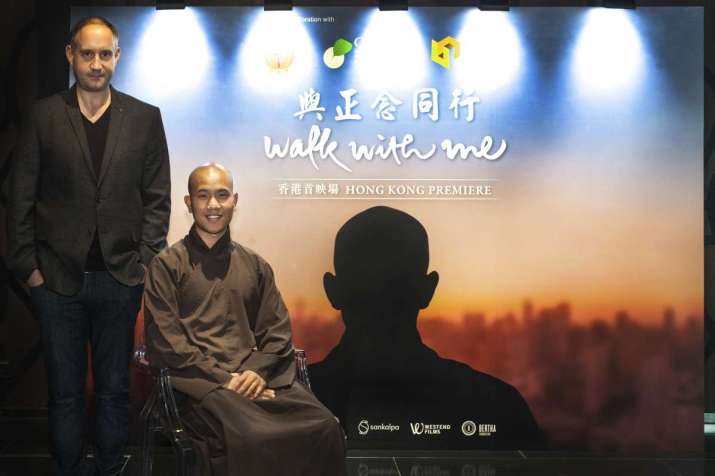

Max Pugh, left, and Brother Phap Huu at the film premiere in Hong Kong. Photo by Buddhistdoor Global

Max Pugh, left, and Brother Phap Huu at the film premiere in Hong Kong. Photo by Buddhistdoor GlobalThich Nhat Hanh suffered a stroke after filming was completed and remains unable to speak. The film includes what might be one of the last scenes of him speaking captured on tape. “It was by pure luck that we filmed his last public years. Hopefully the film will form part of his legacy.” Max observed.

Thich Nhat Hanh recently returned to Vietnam, which brother Phap Huu mentioned “gave us [the sangha] great joy. We always knew he wanted to return, because that is his motherland. . . . So when I heard that Thay had returned, it felt like a child coming home.”

For those of us living in Hong Kong, or similar urban environments, the film does offer an oasis of calm and contemplation in the midst of loud, stressed, and rushed city life—that is, if one is able to accept the pace of the film, face the thunderous silence, and leave our very important daily concerns behind. The best advice I can offer is to truly open up, just sit back and enjoy the ride.

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Thich Nhat Hanh Returns to Vietnam for the First Time in a Decade

Walk With Me Documentary About Thich Nhat Hanh’s Plum Village Community Premieres at SXSW

Thich Nhat Hanh Travels to Thailand to “Be Closer to his Homeland”

Walk With Me Trailer Offers a Glimpse of Forthcoming Thich Nhat Hanh Documentary