FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Finding Excellence, Part 2: A Tradition of Transmission

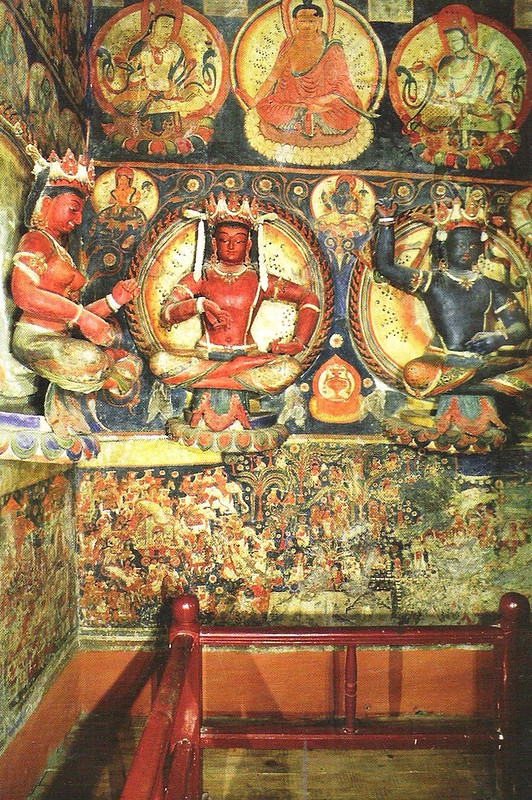

Wi-nyu-nin, protectress of Tabo Monastery, mural painting, 10th century. A pre-Buddhist, possibly Zhang-Zhung deity now called Dorje Chempo; a lasting symbol of ancient transmission coming through Tabo Monastery. From Tabo, Art and History, by Deborah Klimberg-Slater, private publication, 2005, Vienna. p. 47

Wi-nyu-nin, protectress of Tabo Monastery, mural painting, 10th century. A pre-Buddhist, possibly Zhang-Zhung deity now called Dorje Chempo; a lasting symbol of ancient transmission coming through Tabo Monastery. From Tabo, Art and History, by Deborah Klimberg-Slater, private publication, 2005, Vienna. p. 47One needs to take a long view—one that spans vast distances and many centuries—to appreciate the context of the Cham dance traditions that were preserved for the future after escaping the devastation wrought on Buddhist practices during China’s brutal invasion of Tibet in 1950, the quashing of the 1959 Tibetan uprising, and the Cultural Revolution that followed from 1966. High lamas and rinpoches fled Tibet in the 1950s, taking with them memorized sutras, tantras, rituals, and dances, kept alive within their minds and bodies.

Where do dances find sanctuary? The center of this story is the center of many stories: Tabo Monastery, founded in 996 in Spiti Valley in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, is the oldest monastery in continuous use in all of India and the Himalayas. It is also the oldest surviving monastery of the second diffusion of Vajrayana Buddhism, spearheaded by Yeshe O’d (c. 959–1040), ruler of the Guge-Purang Kingdom that extended from Kashmir to Mustang, and his preceptor Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo (958–1055), the famous monk translator.

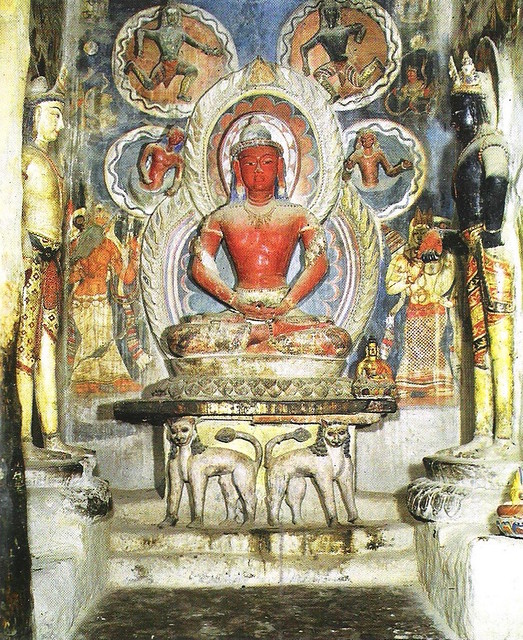

Sculpture of Vajrahasa, in relief, Assembly Hall, Tabo Monastery; part of an

architectural and artistic Vajradhatu Mandala composition executed within the

temple, along which devotees walk. From Tabo, Art and History, by Deborah

Klimberg-Slater, private publication, 2005, Vienna. p. 42

Monasteries established during the first diffusion—initiated and carried out by Padmasambhava in the 7th century—still stand, such as Samye, the oldest of all Vajrayana monasteries. What distinguishes Tabo Monastery is its continuous functioning and role in linking people, cultures, languages, and art during critical periods of Buddhism’s growth and survival. The monastery’s design and decorations are among the most astonishing artistic achievements of the 10th and 11th centuries in the Trans-Himalaya.

In coming to know the character of Tabo Monastery, art history serves dance history. As shown in Figures 1, 3, and 4, we see that the inaugural styles of art from 996 and 1042 share characteristics with the finest Buddhist art of the 10th–13th centuries, in which the body is depicted as the locus of metaphysical transformation.

This art is often associated with the travels of Rinchen Zangpo. Tabo was considered a “daughter monastery” of Tholing Monastery in Ngari, Tibet, established in the 10th century and later transformed into a center for King Yeshe O’d’s monastic and artistic vision. Tabo’s connections with Tholing include Tabo’s role as a trading station as well as a missionary outpost for the king’s expansionist plans.

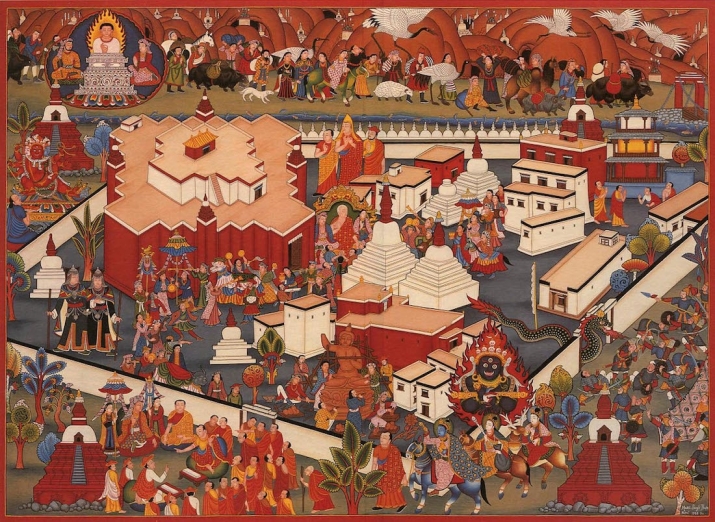

Tholing Monastery, thangka, 20th century, showing the monastery in its heyday before 1600. Tholing was the most important monastery in the Guge Kingdom, and is the oldest in Gnari, Tibet, est. 996 CE. From Records of Tholing, A Literary and Visual Reconstruction of a ‘Mother’ Monastery in Guge by Roberto Vitali, New Delhi, High Asia. 1999

Tholing Monastery, thangka, 20th century, showing the monastery in its heyday before 1600. Tholing was the most important monastery in the Guge Kingdom, and is the oldest in Gnari, Tibet, est. 996 CE. From Records of Tholing, A Literary and Visual Reconstruction of a ‘Mother’ Monastery in Guge by Roberto Vitali, New Delhi, High Asia. 1999The artistic style builds upon the intricate and sophisticated painting of deities in the Ajanta Caves in India’s Maharashtra State that date from before 500 CE. The shading of the body, and intricate decorations, hairstyles, and attire appear in tiered compositions with hierarchies of metaphysical meaning. This original, exuberant style was taken to artistic heights rarely matched in Buddhism, and is due to non-Buddhist artists from Kashmir and Nepal coming into contact with artists from Central Asia, Tibet, China, and India.

In addition to Tabo, the finest extant examples of this style of art can be found in the Alchi Monastery complex in Ladakh, in the surviving 12th century monastery at Wanla, Ladakh, and in the 1,000-year-old Nako Monastery near Tabo in Kinnaur. Central Asian elements, such as rainbow halos, flying dancers, and narrative landscapes, connect Tabo’s art with that found in the Dunhuang Caves, a terminus of the Silk Road in faraway Western China, and perhaps the greatest single record of ancient dances anywhere.

The body depicted as a transformative medium, 11th century. Left to right, Gita,

Vajradharma, Vajrakrsna, three of the 32 boddhisattvas that ring the Vajradhatua

Mandala plan. From Tabo, Art and History, by Deborah Klimberg-Slater, private

publication, 2005, Vienna. p. 41

The art is a kind of ancient virtual reality, designed as an immersive experience through which one walks: text in the form of wall inscriptions, painting, sculpture, and relief combine as figures that are human scale, three times human scale, and in miniature. Landscapes layer with portraits, and narrative painting with abstract religious symbols. It is a metaphysical head-trip meant to destroy and replace mundane perception with the mental formulations of Buddhist yoga.

Of note, regarding the use of the body in this art, is the seeming weightlessness of the bodhisattvas in relief, and the rare mudra (ritual hand positions) shown, some unidentifiable. In Buddhism, circumambulation, following ancient traces, and walking through mandala temples precede the establishment of dance in India, and lay a foundation for its meaning.

Less spectacular, visually, is the transmission of Sanskrit Buddhist texts and manuscripts that followed their own paths to Tabo, in which the monastery played a critical role. Not only did Rinchen Zangpo spend several years at Tabo translating Sanskrit scriptures into Tibetan, but a stream of Indian translators also came to Tabo to learn Tibetan. There, monks ready to teach them collaborated to produce translations of Buddhism’s voluminous literature into Tibetan. These translations were the foundation of Buddhism’s successful second diffusion. Over the centuries, like the artwork that represents the Nyingma, Sakya, Kadampa, and now the Gelugpa teachings, the manuscripts comprising Tabo’s Kangyur, (a set of Buddhist scriptures) are among the most diversely sourced in all Buddhism.

The Cella at Tabo Monastery, 11th century, an explosion of dimension, scale and

media. From Tabo, Art and History, by Deborah Klimberg-Slater, private

publication, 2005, Vienna. p 57

Less well known—in fact unknown until our field research this year, during which we shared copies of a Buddhist dance treatise, The Snow Lion’s Attributes, with monasteries in Himachal Pradesh—is the story of dance lineages being transmitted through Tabo Monastery as it gave sanctuary to lamas fleeing Tibet, defying China’s objective of crushing all Buddhist practice, including Cham.

Thanks to Tabo and a certain monk known as Meme Gyupta (1927–97) who came to Tabo in 1957, and there taught the entire repertory of dances connected with the lineage of Cham from Tashigang Monastery in Tibet, one lineage of Cham dances survived and found a home. I spoke with the current abbot of Tabo, a Tibetan named Kanden Rinpoche, appointed by the Dalai Lama two years ago.

Kanden Rinpoche spoke forcefully about the scale of destruction by the Chinese, who reduced 60,000 monasteries in Tibet to less than 1,000. Despite all this, he affirmed that serious yogic Cham is still performed in the traditional Tibetan region of Amdo to this day as it was seen as something that could be sustained by the monks internally, whatever the external situation.

The Snow Lion’s Attributes, a Drikung Kagyu dance treatise

published by Core of Culture, distributed among

monasteries in Himachal Pradesh. From Core of Culture

Kanden Rinpoche cited the founder of the Sakya school, Konchok Gyalpo (1034–1102), who said that Cham was debased as soon as it was made public. “Cham is not for tourists,” Kanden Rinpoche observed. “Tabo monastery does not advertise its Cham ceremonies, and does not invite anyone outside the monastery’s community, which includes three villages.”

Kanden Rinpoche, the abbot of Tabo Monastery, explains the situation of Cham during the violence in Tibet, to Core of Culture field associate Dechen Lundup, formerly a monk at Tabo. Photo by Konchok Rinchen. From Core of Culture

Kanden Rinpoche, the abbot of Tabo Monastery, explains the situation of Cham during the violence in Tibet, to Core of Culture field associate Dechen Lundup, formerly a monk at Tabo. Photo by Konchok Rinchen. From Core of CultureElder monk Zeten Zangpo entered the conversation to explain how Meme Guytpa (Jampa Tharchen) had taught the monks in 1957, treating Cham as a form of Deity Yoga expanded to become realized as masked dance. “Thanks to Tabo’s remote location and the current paucity of tourists, the monks are able to maintain that virtue in the movement,” he said. “Today there are six older monks who know the name and purpose of each step of every dance. The ceremonies feature 12 dancers, and 14 boys are in training.” Tabo features in three Cham ceremonies: on Losar (the Tibetan new year), during Saka Dawa (marking the birth of the Buddha), and the tri-annual Chakhar Festival.

However, there is no Chams Yig, or dance instruction manual. Fortunately, the six older monks have, between them, all the knowledge to write a Chams Yig for the ancient Tashigang lineage deposited at Tabo 60 years ago. Inspired by The Snow Lion’s Attributes, Seten Zanpo plans to compose a Tabo Chams Yig this winter, with the help of his fellow elder monks. Core of Culture has offered every assistance in this project to produce a lasting document—a memorialization—that will be an invaluable service to Vajrayana Buddhism and a great contribution to world culture.

Seten Zangpo, who was present when Meme Gyupta, escaping Tibet, taught a complete Cham

repertory at Tabo in 1957. Here, he is explaining the rhythms of dances aligned with meditation

techniques to Core of Culture director Joseph Houseal. Photo by Konchok Rinchen. From Core of

Culture.

For more than 1,000 years, Tabo Monastery has served Buddhism as a nexus for realizing great art, promoting trade and learning, translating Sanskrit scriptures, and for preserving for perpetuity the ancient dance traditions. Nowhere was this vitality better seen than in 1996, during the 1,000th anniversary of the monastery, when the current incarnation of Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo held a conversation with the monastery’s pre-Buddhist protectress Wi-nyu-nin, in front of her image, with the help of a medium. Tabo has remained true to its course.

Remote and ancient Tabo Monastery, agent of esoteric transmission. Photo by Konchok Rinchen.

From Core of Culture

Related

Finding Excellence, Part 1: Of Course They Don’t Talk About It (Buddhistdoor Global)

Finding Excellence, Part 3: Who is the Best Dancer Here? (Buddhistdoor Global)

Finding Excellence, Part 4: What Buddhists Do (Buddhistdoor Global)

Finding Excellence, Part 5: A Buddhist Land (Buddhistdoor Global)