FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

Gilded Dharma: A Japanese Lotus Sutra Fragment in Gold on Blue

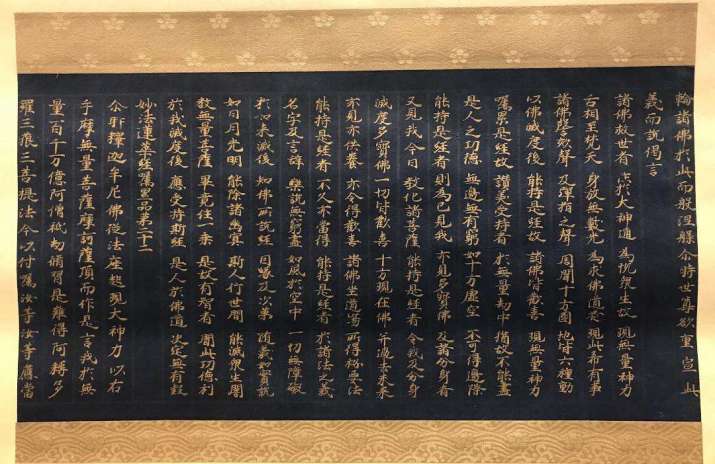

Section of the Lotus Sutra (Jap: Myoho Renge Kyo), Japan, Kamakura period (1185–1333). Gold powder on indigo-dyed paper, mounted on a hanging scroll. Image courtesy of Scripps College, Claremont, California

Section of the Lotus Sutra (Jap: Myoho Renge Kyo), Japan, Kamakura period (1185–1333). Gold powder on indigo-dyed paper, mounted on a hanging scroll. Image courtesy of Scripps College, Claremont, CaliforniaAmong the most interesting but least exhibited works of Buddhist art are the sacred texts, or sutras, that contain the teachings of the Buddha. These texts are inscribed on a range of materials depending on the region and the patron—from wood and bamboo to paper and silk, and typically feature the most refined calligraphy of the region as well as, in some cases, a frontispiece or illumination rendered in the finest hand. Some of the most exquisite and precious examples of these sacred Buddhist texts are the East Asian sutras written in gold on indigo-dyed paper. Scripps College in Claremont, California, recently acquired a fragment of a Japanese blue-and-gold sutra mounted onto a vertical hanging scroll that is an elegant example of the skill and devotion expressed by Buddhist artists and their patrons in the visual presentation of the Buddha’s teachings.

The teachings, or Dharma, were first written down around 2,000 years ago as Buddhism flourished into different schools and spread throughout Asia. Over the centuries, these Buddhist traditions have varied in philosophical focus and devotional practice, but they all employ sacred texts to some degree. Sutras have been used as teaching materials and supports for ritual practice, employed as handbooks for monks, and read or recited to laypeople during religious ceremonies. They are also sacred objects in themselves, and have been crafted as commemorative offerings in honor of deceased individuals. The production and the sponsorship of these often elaborately decorated and illuminated manuscripts were regarded as great acts of devotion and a means to earn merit.

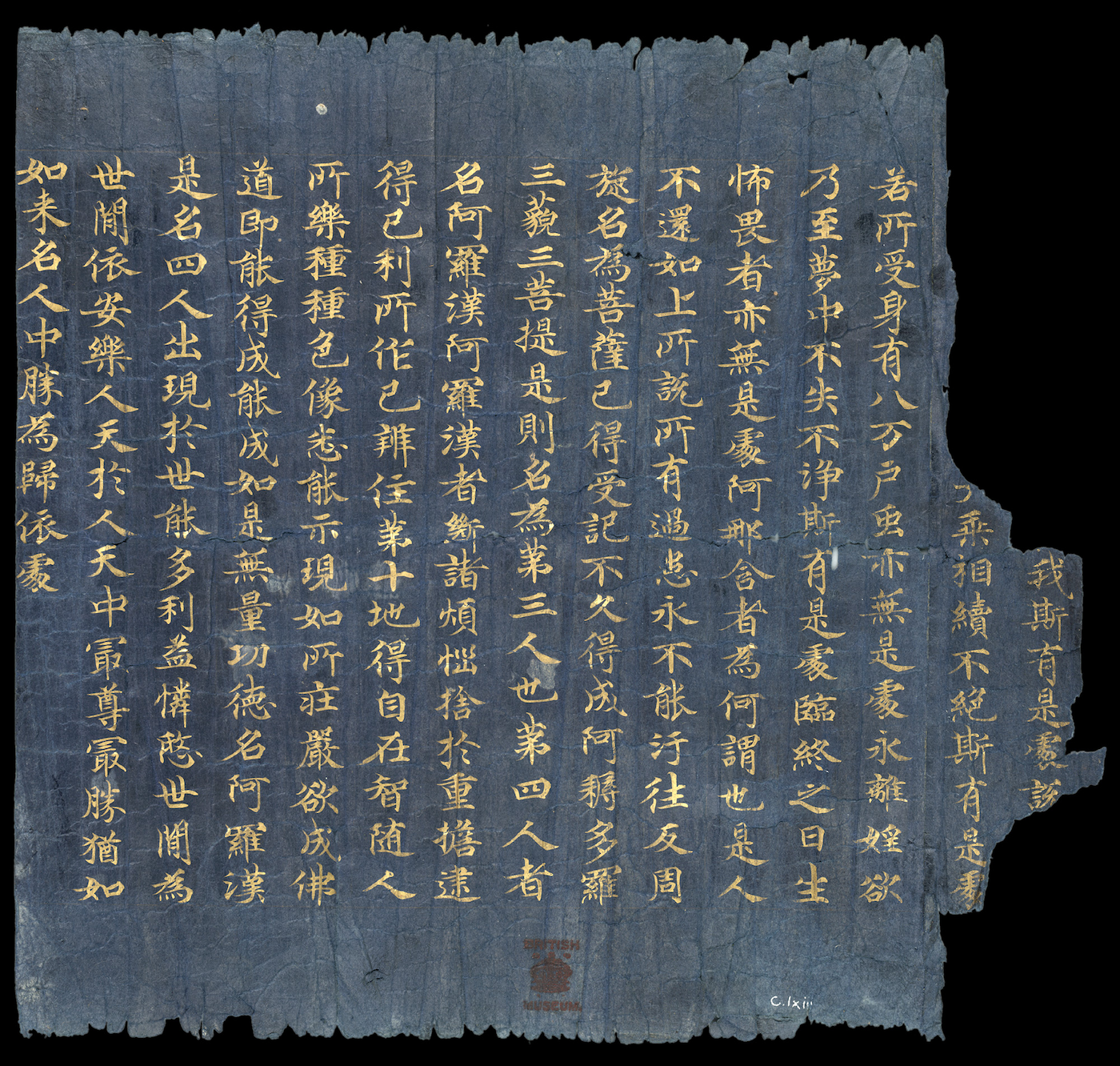

Fragment of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, China, ninth or tenth century.

Image courtesy of the British Library

Sutras written in gold ink on blue paper were first created in China in the Tang dynasty (618–907). They were made of sheets of paper that were colored a deep blue or purple using dye from the indigo plant native to China. The sheets were glued together to form long, horizontal scrolls onto which monks inscribed vertical columns of text in Chinese characters using a brush dipped into a pigment mixed from gold powder and glue. The paper scroll was mounted onto a backing made of paper and silk brocade and was then rolled closed for storage and unrolled for reading. Although these time-consuming and expensive scrolls were stored with the treasures of the temple, few have survived in their entirety. The earliest example of a Chinese blue-and-gold Buddhist sutra text is a fragment of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra dated to the ninth or tenth century that was removed from the cave temples of Dunhuang by British archaeologist Sir Aurel Stein and is now in the collection of the British Library in London.

Such scrolls were likely carried by monks to Korea and Japan during the Tang dynasty and copied by monk-artists in Korean and Japanese temples. As in China, early examples of Korean and Japanese sutras scrolls are very rare, and although some later complete scrolls do exist, most examples of blue-and-gold sutras have survived as fragments. Even so, these fragments are so sacred and artistically refined that they often rank among the most highly treasured objects in temple, museum, and private collections. The Scripps College sutra fragment dates to the Kamakura period (1185–1333) and comprises 23 vertical columns of sutra text from the end of Chapter 21 and start of Chapter 22 of the Lotus Sutra (Skt: Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra), one of the most important and influential texts of Buddhism.

Lotus blooming in a pond. Photo by the author

Lotus blooming in a pond. Photo by the authorAccording to Buddhist legend, the Lotus Sutra was created at the time of the Buddha, but its content was withheld for hundreds of years until humanity was considered to be ready to understand it. It was written in several stages and probably completed around 200 CE. The text contains concepts that are crucial to Mahayana Buddhism: namely that the Buddha is an eternal being who can manifest in different ways, and that the instruction of his teachings, or the Dharma, should be skillfully adapted and presented so as to be accessible to a wide range of people. The sutra stresses the idea that all beings have the potential to attain enlightenment and to become a buddha, just as a beautiful white lotus can bloom in the muddiest of waters (a translation of chapters 21 and 22 can be found in the Buddhistdoor archive).

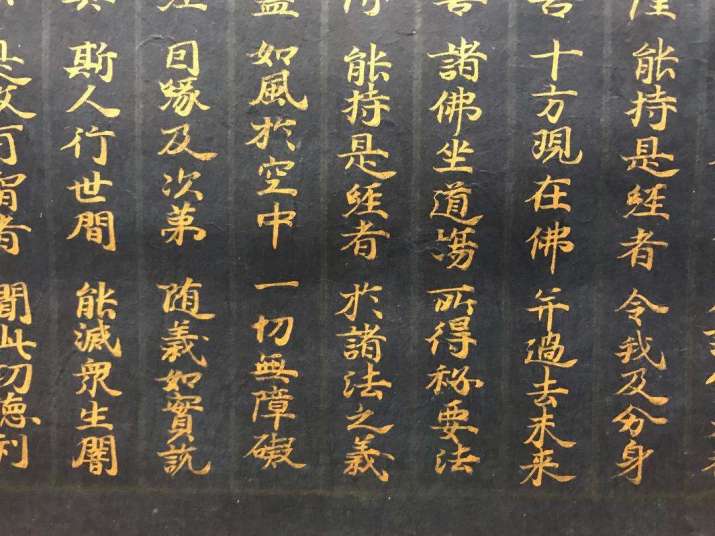

The Lotus Sutra, detail, Japan, Kamakura period (1185–1333). Image courtesy of Scripps College, Claremont, California

The Lotus Sutra, detail, Japan, Kamakura period (1185–1333). Image courtesy of Scripps College, Claremont, CaliforniaThe Lotus Sutra was already firmly established as a Buddhist text in Japan prior to the Kamakura period, an era when Buddhism was strongly embraced by all levels of society, from the Imperial Court and the military elite to the general populace. The sutra was the main text of the Tendai school (Chinese: Tiantai, Korean: Cheontae), which was brought to Japan from China in the ninth century by the monk Saicho (767–822), and became the dominant form of Buddhism for the next couple of centuries. During the Kamakura period, a Tendai priest called Nichiren established a new school based on the belief that the Lotus Sutra is the Buddha’s ultimate teaching. For Nichiren, the title was the essence of the sutra, “The Seed of Buddhahood,” and chanting the phrase “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo” (Glory to the Sutra of the Lotus of the Supreme Law), or worshipping a calligraphic mandala of the same phrase (known in Japanese as a gohonzon) were the highest practices of Buddhism. Such reverence for this sutra undoubtedly led to the creation of many copies, some in gold ink on blue paper, like this example.

Although it is difficult to know for whom and by whom this sutra was created, we know by the high quality of the calligraphic inscription that it was made by a skilled scribe, most likely a priest who wrote out such texts regularly and was accustomed to writing in a pigment and texture that differed considerably from charcoal ink on smooth white paper or silk. Hiring such a skilled monk to inscribe a Buddhist text in gold would have been expensive, so it was likely commissioned by a member of the nobility or military elite as an act of piety, perhaps to help them, their family members, or ancestors to attain religious merit. Although today the sutra has only survived in part, we can still appreciate, centuries later, the artistry, hope, and devotion that fill the 23 gilded lines.

See more

Chinese Buddhist sutra on indigo-dyed paper (British Library)

Chapter Twenty-one: The Spiritual Powers of the Thus Come One (Buddhistdoor archive)

Chapter Twenty-two: The Entrustment (Buddhistdoor archive)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Inner Immensity at the Great Assembly

“Beauty that Floats on Mud”

Shakubuku! The Advent of Nichiren Buddhism in India

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Rotating Buddhist Sutra Case Promoted as National Treasure in South Korea

World’s Largest Buddhist Sutra Calligraphy Moves Visitors

Archaeologists in China Unearth Sutra Translation by Tang Dynasty Monk Xuanzang