FEATURES|COLUMNS|Art of Living

Going to “the Place that Nobody Wants to Go:” Pema Chödrön and Moana

One of the most common questions asked by practitioners in all spiritual traditions is an exceedingly simple one: “What is the most effective way of responding to difficult emotions?” As Roger Walsh writes in Essential Spirituality, a book that distills the major wisdom traditions of the world into seven main practices, “Learning how to respond skillfully to painful emotions is one of life’s most crucial challenges. . . . It is a tragedy so few people know how to work effectively with their emotions and so few are masters of emotional wisdom.”

One of the most consistent instructions given by contemporary “masters of emotional wisdom” is to simply allow oneself to fully experience painful emotions without resistance.

“Simple,” as Jon Kabat-Zinn often says. “But not easy.”

And yet, when we look at the personal accounts of spiritual adepts who, as Walsh says, “know how to work effectively with their emotions,” this is one of the most consistent instructions we find. There is, of course, the example of the Buddha himself, who confronted Mara and everything he represented beneath the Bodhi Tree.

Buddha Confronting Mara, by Shri S. Sen Roy, New Delhi

Buddha Confronting Mara, by Shri S. Sen Roy, New DelhiTo take a more contemporary example, Pema Chödrön recounts the following transformative experience she had while on a small, close-quarters retreat with a woman who was extremely angry with her, yet refused to discuss the situation:

It brought up feelings in me of not being okay. It just triggered the whole thing. And I tried all the meditation techniques I had been teaching for years. I tried everything, and nothing really got at it. So one night, because I couldn’t sleep, I went up to the meditation hall and I sat all night long and I wasn’t even really meditating. I was just sitting in this raw pain, with almost no thoughts about it, like on fire, practically.

And then something happened. I guess I was involuntarily just staying because it was so painful I couldn’t move. And something happened, transformative. Which is that I just had this completely clear insight that my whole personality—what we would call ego-structure—was based on not wanting to go to that place. That everything I did—the way I smiled, the way I talked to people, the way I tried to please everybody—it was all to avoid going to that place.

But I now feel that, learning to stay, we do reach that place, the place that nobody wants to go. And our whole façade, and our whole little song-and-dance that we do, our whole superficial shtick is based on not wanting to go to that place. And once you’ve touched it . . . basically, you get pretty fearless. Because then there’s nothing to hide, and you’re no longer invested in the ignorant dance of trying to move away from it constantly, all the time.

Simple. But not easy.

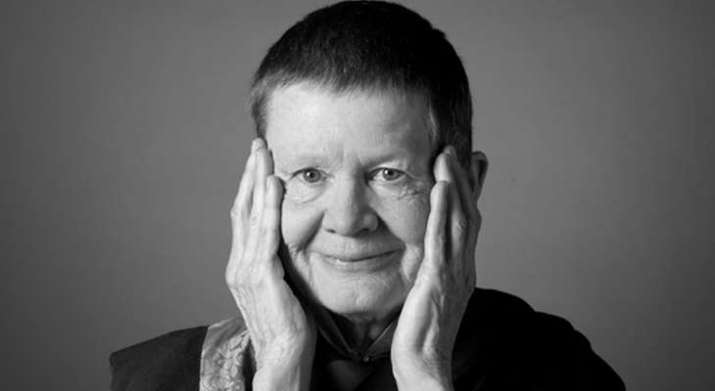

Pema Chödrön. From ramdass.com

Pema Chödrön. From ramdass.comAnd yet, we find the same basic experience recounted by innumerable other celebrated practitioners, including Siddhartha Gautama, Joseph Goldstein, Rupert Spira, Rainer Maria Rilke, and . . . Moana.

Wait, Moana, the titular character from the recent animated Disney film? Yes, that Moana. The climax of the movie, as I submit below, suggests the same basic methodology for handling difficult emotions that Pema and many other spiritual masters describe. However, by appealing directly to our senses and feelings, and doing so in fictional imagery with which we are culturally familiar, I believe the film has the potential to convey this way of handling difficult emotions in a more immediate and lasting way than abstract philosophy.

Here’s the climax of the movie, which you might want to watch before reading on:

At the beginning of this climactic scene, the legendary shape-shifting demigod Maui has come to the end of a brutal and ferocious war with the demon Te Ka, in which he has met her violent actions with equal and opposite reactions, and tried his best to use brute force and cunning to defeat her.

Maui can be seen as a personification of all the violent ways we do battle with our unwanted, unpleasant, or disagreeable emotions, by trying to eliminate, outsmart, deceive or defeat them.

It doesn’t work.

From disney.wikia.com

From disney.wikia.comAfter Maui viciously slices off Te Ka’s arms with his magical fishhook, her arms quickly regenerate. She is, after all, made of magma, the molten rock that wells up, irrepressibly, from deep within the Earth. It’s the old lesson: what we repress, returns; what we resist, persists; what we avoid, gets redeployed. The most we can hope for from our attempts to suppress our inner experiences is what Maui gains from his attempts to vanquish Te Ka: short-term relief.

Very short term. Because the short-term gain quickly snowballs into long-term pain. Maui’s attacks only enrage Te Ka; enflaming her, stoking her ferocity, adding fuel to her volcanic fire until she is hurling not snowballs but fireballs at him, doing her utmost to destroy him.

Like Maui’s aggression, Te Ka’s rage is not just unhelpful, but harmful. After all, it leads her and Maui into exactly the same predicament they were in a thousand years prior, with Maui charging Te Ka in a full frontal assault, and Te Ka reacting with a head-on punch that produces an explosive white flash that both mirrors and echoes the one that ended their conflagration a millennium earlier. This earlier confrontation was also costly in that it not only caused Maui to lose his magical fishhook, but caused Te Ka to lose the very thing she was originally fighting to retrieve: her own tender heart. Both fishhook and heart sink into the depths of the sea, where they remain for a thousand years until Moana’s grandmother finds the heart, and tells Moana to bring it to Maui so he can return it to Te Fiti, at which point the circular uproar begins again, only to end in nearly the exact same way.

As the comedian Moms Mabley used to say, “If you always do what you’ve always done, you will always get what you always got.” If you want a different outcome, you have to do something different.

Moana does something different.

When she looks at the spiral on the glowing green heart in her palm and then at Te Ka, she sees that Te Ka has a similar spiral on her chest: the missing heart she believed was Te Fiti’s actually belongs to Te Ka because Te Ka is Te Fiti.

In the opening sequence of the movie, when Moana’s grandmother tells the myth of Te Fiti and Maui, she implies that they are two separate beings. After stealing Te Fiti’s heart, she says, “Maui tried to escape, but was confronted by another who sought the heart: Te Ka!” So throughout the movie Moana has believed that Te Ka is distinct from Te Fiti, but she now realizes that they are not two, that Te Ka is the personification of Te Fiti’s reaction to being violated; that beneath Te Ka’s glowing black-and-orange exterior lies a wounded goddess who has, like so many other women, been violated, robbed of her power, stripped of her magical, life-giving heart. Just as Pema says, beneath the angry ego-structure or the enraged personality that is Te Ka lies “that place” or “the place that nobody wants to go.”

Anger is often referred to as a “secondary” emotion for the simple reason that it does not come first. What precedes it—often by a mere split-second—is something infinitely more vulnerable, a word that comes from the Latin vuln meaning wound, or wound-able. Which is precisely why we so often react to our primary, hidden emotions with secondary, protective emotions: because we don’t want to be wounded. Again. So we take the form of Te Ka, the secondary, protective, hard and visible manifestation of something much more primary, vulnerable, soft, hidden. When, like Te Fiti, we can’t bear to feel disheartened, we often wind up behaving like Te Ka: heartlessly.

Hurt people hurt people.

But hurt people also heart people, as in love them. And hurt people also heal people. At least some do. And Moana is one of those hurt people who both heartens and heals people precisely because she is able to help them go to what Pema describes as “the place that nobody wants to go.” What allows her to do this is her talent for what, in contemporary psychological terms, is variously termed “cognitive reappraisal” or “reframing” or “altering the context” or “changing your mindset,” all of which are different terms that mean the same basic thing: when you change the way you view your circumstances, not only do your circumstances change, but so do your feelings about your circumstances. When Moana sees that Te Ka is Te Fiti, it changes her view of her circumstances, which in turn immediately changes both her circumstances, and how she feels about them.

More specifically, her sudden realization that Te Ka is Te Fiti is a “completely clear insight” that, like Pema’s, not only allows her to “get pretty fearless,” but gives her the courage and, more importantly, the compassion to confront Te Ka. In contrast to both Maui and Te Ka, Moana’s “cognitive reappraisal” of Te Ka is what allows her to tell the ocean, the one thing protecting her from the terrifying, demonic demi-goddess, “Let her come to me.” She lowers her defenses, allows the pain, makes space for it, welcomes it. Maui stands in awe, gobsmacked as he watches her do something that has never even occurred to him: to drop the tough guise and rather than fight the pain, meet it and greet it. As Te Ka comes to Moana, the ocean parts and Moana walks toward Te Ka in a scene that echoes that iconic spectacle in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, when Moses lifts his staff and God parts the Red Sea to free the enslaved Israelites. In both movies, spiritual ignorance results in slavery, the salvation from which is itself spiritual.

From pinterest.com

From pinterest.comMoana then walks slowly, gracefully, toward Te Ka, her glistening brown hair blowing in the wind. Time slows, not just because she is present, but because she is presence itself, and her timeless presence is just that—a present, a gift, not just to Te Ka and Te Fiti, but to herself, to Maui, to her people, to the whole Earth. She is grounded, like her bare feet are grounded in the sand as she walks, “kissing the earth with her feet” as Thich Nhat Hahn says, grounded in the ground of being. The Earth is her witness, just as it was Siddhartha’s witness when he touched the ground beneath the Bodhi Tree in the moments preceding his enlightenment. What touches the earth and the Earth itself are not two. They are interdependent, not separate, just as Te Ka is not separate from the goddess beneath her, and Moana is not separate from the demon goddess with whom she is about to exchange breath.

And as she walks toward Te Ka, she sings:

I have crossed the horizon to find you

I know your name

They have stolen the heart from inside you

This does not define you

This is not who you are

You know who you are

From medium.com

From medium.comWe all have to cross the horizon to reach “the place that nobody wants to go.” It takes a lot of “learning to stay” before we can finally “touch” the ground that our ego-structures are based on. It doesn’t happen right away or all at once. Zeal doesn’t work; patience and willingness do. And, as Moana says, it also helps to be able to see and, more specifically, “know the name” of what lies beneath the secondary, reactive emotions. After all, it is only when Moana sings, “This does not define you. This is not who you are,” that the heat of Te Ka’s anger begins to cool and she fades from glowing red to cool black. Moana has seen her, understood her, recognized her. Her words calm and soothe Te Ka because they touch “that place”—that tender place inside her which used to hold her heart—her non-conceptual capacity to feel and love and create and trust and know.

Her words also touch the indefinable place beneath “the place that nobody wants to go,” a place that is unwoundable because it is transcendent. It goes by many names, both religious and non-religious, atheist and secular: the observing self, the self-as-context, consciousness, awareness, clear light, ground of being. The list goes on. Different words that all point at the same basic experience, of a “place” that is in fact no-place (which is, perhaps not incidentally, the literal definition of utopia) because it is impalpable, limitless, contentless, everywhere, nowhere.

The most common Buddhist metaphors liken this “place” to the sky which remains unscarred by even the most violent storm clouds, or the depths of the sea that remain undisturbed by the most violent waves. This is the sense of self that Moana is referring to when she tells Te Ka, “This is not who you are. Who you truly are.” In this instance, the qualification “truly” does not just mean authentically or primarily; she is referring to Te Fiti, Te Ka’s transcendent self. This is a supremely important and practical distinction for the simple reason that it is a lot easier to go to “the place that nobody wants to go,” as Pema implores us all to do, if we have placed that “that place” in the context of a spacious, expansive, infinite no-place that contains it, transcends it and cannot possibly, as Moana says, be defined by it.

From shelidon.it

From shelidon.itIt is only after Moana has whispered these words that Te Ka finally closes her fiery eyes and allows Moana to lean forward and touch her forehead in the Polynesian ritual known as hongi. Traditionally, the ritual serves a similar purpose to a handshake, except that in the hongi, the “breath of life” or ha is exchanged, which is also sometimes interpreted to mean that the participants’ souls are being shared. The ritual is also a re-enactment of the way, in Maori mythology, the gods breathed life into the first woman’s nostrils. In performing this ritual, therefore, Moana is not only greeting Te Ka, the embodiment of fear, but breathing life into that fear by reminding her fear that the two of them are, in fact, not two, not I-it but I-thou. What’s more, the image of their foreheads touching also suggests that Moana is not just “facing her fear,” or turning toward it rather than away, but that she is, as Pema says, “touching” her fear. Touching is not a cerebral, intellectual, or cognitive exercise, but a palpable, experiential and sensual act. Moana doesn’t just face her fear, she touches it. And she doesn’t just touch the face of her fear with her hands, she touches the face of her fear with her own face. It is, finally, this exquisitely tender, intimate, and compassionate action that allows Te Ka to lower her guard and not only go to “that place” but go to that other place, that utopian no-place, beyond it: Te Fiti. What is the most effective way of responding to difficult emotions? Like this.

References

Walsh, Roger. 2000. Essential Spirituality: The 7 Central Practices to Awaken Heart and Mind. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Mustard Seed of Grief and Rebirth

The Positive Impact of Mindfulness

Josh Korda: Where Buddhism, Life, and Psychology Meet

Loving your Tick: Book Review of Mindfulness as Medicine