Several years ago in Bangladesh, I participated in the Honey-offering Festival being observed at my master’s monastery. As per tradition, thousands of lay followers came to the temple dressed in white to pay their respects to the Buddha and monastics. Five monks, myself included, were present, with lay followers seated before us on mats spread on the floor. The lay practitioners pledged to observe the five precepts—to refrain from taking life, stealing, sexual activity, lying, and intoxicants—and many also vowed to observe the eight precepts during the ceremony that my master conducted. The second part of the ceremony was marked by a long period of chanting, paying homage to the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the sangha, followed by offerings of food, flowers, incense, and lamps. The participants shared the accumulated merit with friends, relatives, and all sentient beings.

FEATURES|THEMES|Festivals and Teachings

The Honey-offering Festival: Commemorating the Service of Animals to the Buddha

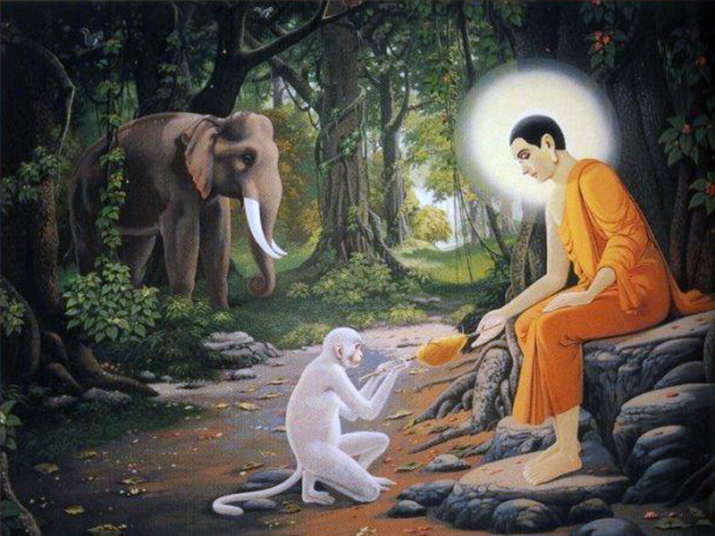

The Buddha with the monkey and the elephant in Parileyya Forest. From scentsofgrace.blogspot.hk

The Buddha with the monkey and the elephant in Parileyya Forest. From scentsofgrace.blogspot.hkThe Honey-offering Festival is a Buddhist religious ceremony that commemorates the service and sustenance provided by animals to the Buddha during his 10th rains retreat at Parileyya Forest. According to legend, during his retreat a monkey brought a honeycomb for the Buddha to eat, while an elephant brought fruit and protected the Buddha from fierce animals.

When the Buddha accepted the gift of the honeycomb, the monkey, overjoyed, began to leap from tree to tree, but suffered a deadly fall in his reckless jubilation. Because of his generous gift, however, the monkey was immediately reborn in the Heaven of the Thirty-Three (Pali: Tavatimsa), the second of the six heavens in the Desire Realm. Since these events are believed to have taken place on the day of the full moon, the occasion has come to be commemorated as Madhu Purnima, or “honey full moon.” The festival is observed on the full moon of the 10th lunar month, mostly by Theravada Buddhists in South and Southeast Asia.

This year the festival falls on 28 September, and Theravada Buddhists in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and elsewhere will observe it by offering honey and other foods as alms. As an Uposatha—a Buddhist day of observance that dates back to the time of the Buddha and during which members of the sangha and lay practitioners observe their practice more deeply—the Patimokkha, the basic code of rules governing conduct within the sangha, is recited. Traditionally, a minimum of four monastics is required to recite the Patimokkha; however, in circumstances when fewer monastics are present, the Vinaya prescribes alternative activities. The most senior monk of the group leads the ceremony, following a ritual for mental purification.

Lay Buddhists also play an active role in commemorating the day, many of them observing the eight precepts (Pali: Uposatha Sila):

1. To refrain from taking life.

2. To refrain from stealing.

3. To refrain from sexual activity.

4. To refrain from lying.

5. To refrain from using intoxicants.

6. To refrain from eating at the improper time.

7. To refrain from dancing, singing, wearing garlands, and perfumes.

8. To refrain from lying on luxurious sleeping places.

They can also practice meditation, listen to Dhamma talks, recite suttas, and participate in other ritual activities.

Thai lay practitioners offering honey to monks. From thaibuddhist.com

Thai lay practitioners offering honey to monks. From thaibuddhist.comThe session concluded shortly before noon with offerings of honey from the lay practitioners, who lined up as the monks, bearing alms bowls, passed by following the senior monk. Until the offering was given, all the devotees softly uttered: “Sadhu, sadhu, sadhu . . .,” a Pali word meaning “good,” “excellent,” or “auspicious.” Those who had chosen to observe the eight precepts then ate lunch at the same time as the monks. In accordance with Theravada tradition, they did not eat in the afternoon during their observance of the eight precepts, taking only liquids such as juices. They were accorded additional respect from other attendees, who offered them juice in order to accumulate merit. Afterwards, the other attendees also ate, and presented charitable donations of clothing, medicines, food, and other items for needy people. Visitors could then leave or choose to remain at the temple to attend a Dhamma talk, engage in discussion, read Dhamma books, or to practice meditation.

The observances concluded in the evening with chanting, when new attendees joined the group who had undertaken to observe the five precepts. Those observing the eight precepts kept them until the next morning, thus continuing the Honey-offering Festival until the next day. The next morning those observing the eight precepts returned to the temple to mark the end of their vow, although they continued to observe the five precepts in their daily lives.

The festival is also significant as it marks an event that underlines the importance of harmony within the sangha. While the Buddha was in Kosambi in ancient India, a dispute arose among his monastic followers over whether it was permissible to leave the water scoop in the latrine. The Buddha attempted to resolve the quarrel amicably but was unsuccessful, so he left and retired to Parileyya Forest to show his dissatisfaction with their conduct. It was during his solitary retreat in the forest that the monkey and the elephant fed the Buddha.

As the argument between the monks escalated, with neither side willing to concede to the other, the Buddha’s lay followers demonstrated their loss of respect for the monks by refusing to offer alms. It was only then that the monks finally decided to resolve their dispute, seeking the Buddha’s forgiveness and vowing to live together in harmony. The Buddha pointed to the elephant and counseled the quarrelling monks, saying that if it is possible to cultivate wisdom with diligence and live with consideration for one another, they should do so; if it is not possible, then, like the elephant, it would be better to live alone because foolish associates only increase one’s own suffering.

See more

The Honey Offering Festival, Samut Sakhon Province (encyclopediathai.org)

Honey Offering Ceremony at a Thai Temple (Buddhism in Thailand)

Buddhists celebrate Madhu Purnima (The News Today)

The Quarrel at Kosambi (nichirenscoffeehouse.net)