FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Immortality and Invincibility, Part Two: Notions of the Body, Concrete and Subtle

Exploration into the intersection of Taoism and Buddhism finds a fundamental premise of distinction in disparate notions of the body. Notions of the body in different cultures and epochs is not a topic often treated. So, before going into a more detailed description in Part Three of how Taoist and Buddhist notions of the body contrasted first and integrated later, this article presents a series of images, which could be also another series of images, to offer a consideration of what is meant by “a notion of the body.”

What is a human body and what is it supposed to do? What is it capable of doing and what does it signify, when used didactically or symbolically in art or esoteric transmission? Is the body a vessel of spirituality or a hindrance to abstract understanding? Is the body about perfection or is it merely something to conquer and transcend? Should it be honored or abandoned? At its best, is a body hard or soft? Is the real body invisible?

It should be pointed out that the examples below are of the human body, not the bodies of deities or supernatural beings.

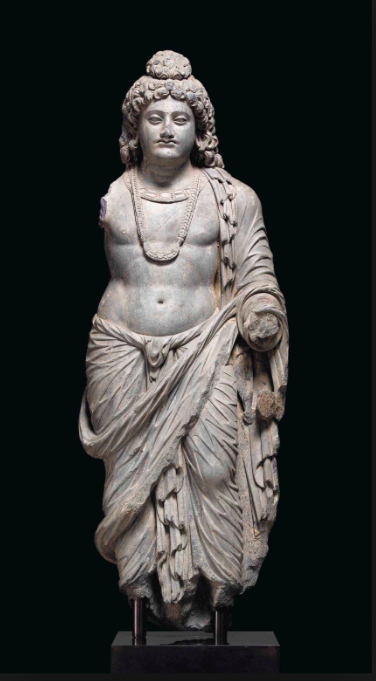

Grey schist figure of a bodhisattva. Gandhara, second or

third century. Image courtesy of Christies

This Gandharan bodhisattva from what is now Afghanistan depicts a Buddhist enlightened one, while looking more like an ancient Greek athlete. It is whole, self-contained. Gandhara is a region conquered by Alexander the Great. To this day, one will find blonde-haired, green-eyed people along with blue-eyed, black-haired people in the region. Aesthetically, the philosophical aspiration of the bodhisattva is expressed through bulging muscles, curly locks of hair, and somewhat stoic but handsome Western facial features: an aquiline nose, almond eyes, and bow shaped mouth.

Physical accomplishment and strength, characteristics of Greek art, are borrowed to reveal spiritual attainment and protection, characteristics of bodhisattvas. Two notions of the body are integrated. The bodhisattva is standing in a relaxed pose, torso exposed, with his weight resting on his right leg and his left slightly bent. He is wearing a dhoti tied at the waist and a sanghati with cascading folds of drapery, a sculptural treatment of fabric also borrowed from the Greeks, to better reveal musculature.

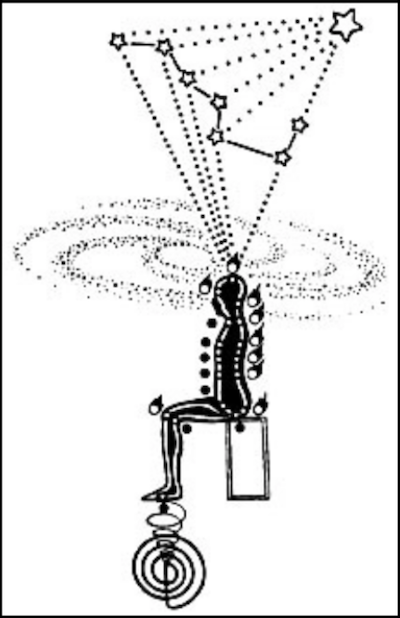

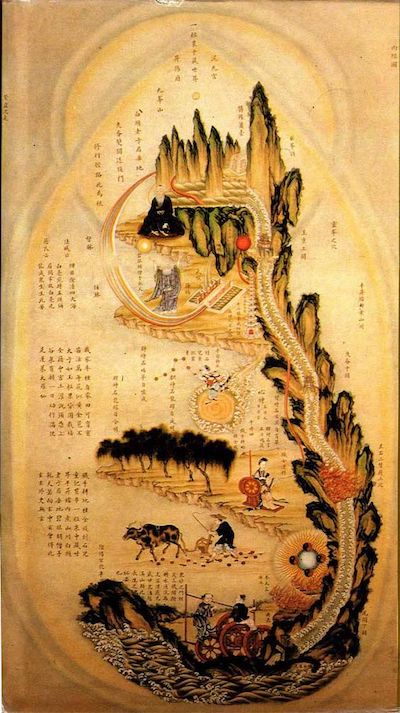

A Taoist schematic of the macrocosmic orbit, a

psycho-physical meditation practice connecting the heavens,

the Earth, and one’s body. From Core of Culture

The second image here is a diagram, a schematic for a Taoist meditation and energy circulation practice known as the macrocosmic orbit, part of a collection of related techniques called neidan. The practice relies on the layered understanding of five bodies: the zhi body connecting the physical body to the deepest energy of the Earth, affirming the human as an earthly creature; the po body or breath body uniting the physical body to the air of the Earth, an energy that extends beyond the skin and physical form; the wu, or shen body, which realizes the undifferentiated substrate that flows in all things; the yi body or body of light, which is a germinal essence outlasting physical form; and the hun body or astral body, which bears the imprint of the stars and determines our personality.

These five bodies create a framework for the circulation of qi within the physical body. That qi can then extend through the body, deep into the Earth, and draw from deep space as well, aligning with the pole star, as cosmic energy is poured into the physical frame. Indeed the planetary orbits and paths of the stars are considered circuitry. Here, in neidan, the physical form is the locus of circulating energy, expanding to reveal and partake in the full reality of human nature as a cosmic being.

Discobolus, the disc thrower. Roman marble copy of a lost Greek bronze original by the sculptor Myron. Image courtesy the Vatican Museum

Discobolus, the disc thrower. Roman marble copy of a lost Greek bronze original by the sculptor Myron. Image courtesy the Vatican MuseumThe third image here is the famous Discobolus, or disc thrower, called by some the most perfect sculpture of the human form. In showing a perfection of physical form, it nonetheless depicts human potential as the athlete is about to release the disc. The ancient Greeks defined a style of sculpture called rhythmos that embodied harmony and balance, and in doing so, revealed sublime beauty, the beauty of the athletic male form. It is important to note that this perfection belongs to a man, not to a god.

The harmony, balance, and proportion indicate a similar mind, one concerned with philosophical development, character, and attaining the heights of human possibility. Nudity has many reasons in art. In Discobolus, the nudity expresses honesty and the complete attainment of principle from all angles, including the intellectual. Greek athletes competed in the nude, so the sculpture is factual. A total symmetry occurs. Athletes represented places, and their honor was the honor of a whole city. This personal perfection is a matter of civic glory. The beauty, mathematical rigor, perfection, and grace belong to all Greeks, not to Discobolus alone. His body means much more than a single man’s body; it symbolizes what man can be; a fundamental ideal of ancient Greek civilization.

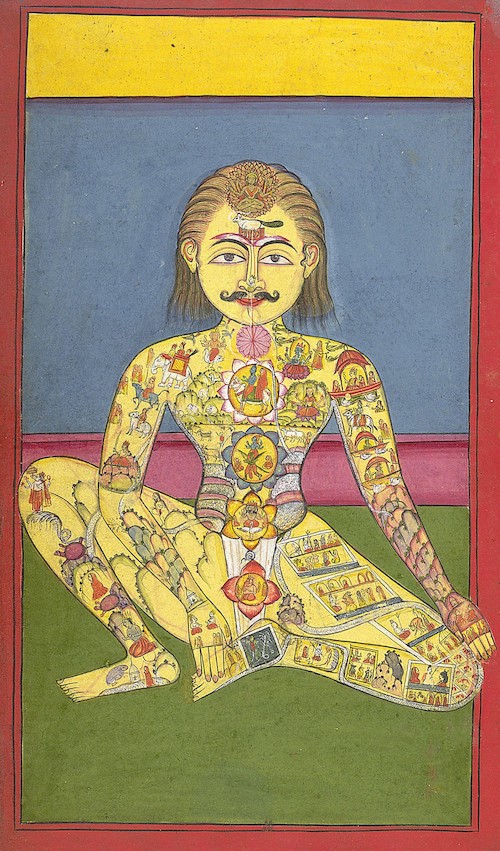

The subtle body with chakras in Indian tantric mysticism. Yoga manuscript, 1899.

Image courtesy of the British Library

The fourth image here treats the human body as a yantra, a kind of mystical diagram shaped by essential primordial sounds. This human-as-yantra diagram is designed to assist practice, called sadhana. The word sadhana implies that to attain a thing is to know it in its ultimate sense by being that thing, and this necessitates substantial exertion, cosmic reflection, and self-generation. Early writers on tantra, yoga, and natya (dance) emphasized that the highest importance of any form was reached in its practice. The body is conceived of as a vibratory field.

Fundamental to Indian yogic techniques is the central column rising straight through the torso, from perineum to the crown of the head, punctuated by psychic-energy centers, called chakra, usually seven in number. Each chakra, beginning at the base of the torso, represents a three-dimensional unfolding flower-shaped vessel, becoming more complex and refined as the chakras rise, one upon the other.

The lowest chakra has merely two petals, the highest has many, some say 32, some say a thousand, as such there is a spiritual progression from lower to higher consciousness. Each chakra is generated by a sound particular to it, has its own vibratory field, and corresponds to a point on the spine. These sounds in sequence form one kind of mantra, inviting a series of particular deities to be present in each chakra. Placing the elements and other universal entities on different parts of the body, the meditator makes his body cosmic. This function of tantra means reflection of godliness in every aspect and being within the universe, including the human body. The meditator, who longs for gnostic union, is energized and awakened to a higher self by the chakras.

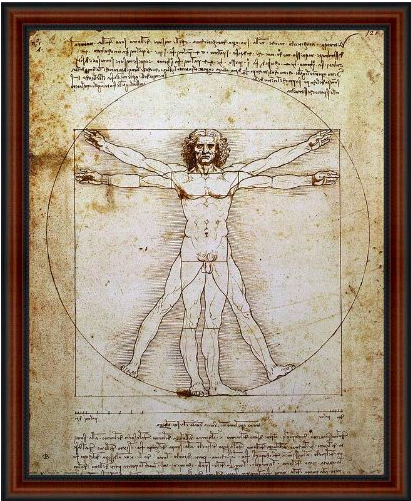

Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1490. Drawing, ink on

paper, page of a notebook. From Core of Culture

The famous Vitruvian Man by Italian renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci depicts a man in two superimposed positions, with his arms apart, and legs both together and apart. His whole body is inscribed within a circle and square. The drawing is based on the notion of ideal human proportions derived from Euclidean geometry as applied to architecture by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise, De Architectura. Vitruvius described the human figure as being the principal source of proportion within the classical geometric schematics of architecture.

In short, da Vinci showed the human male body encased in Euclidean forms—the square, the rectangle, and the circle—as per Vitruvius’ concept that the ideal human form should be the basis for scale and proportion in the buildings where humans lived and worked: man as the measure of concrete civic structure. In fact this is not such a new idea. Even primitive man made homes to suit his size and lifestyle. But this approach claims an ideal, one with far-reaching consequences, bordering on philosophical hubris. Is man the measure of all things? Vitruvian Man makes a seminal case for the concrete reality that man’s true nature, indeed his physical animal self, is the measure of the ordered world.

Taoist Neidan meditation diagram of the body’s inner landscape.

Painter unknown, 19th century. From Core of Culture

One basic dynamic of Taoist meditation is reversal, to reach undifferentiated reality by going backwards. This image appears in several forms in Taoist esoteric literature: as a drawing, an engraving, a stone print, and a painting. It integrates completely with the macrocosmic orbit above, being the microcosmic orbit that takes place within the meditator’s body. What is unique and beautiful about this schematic is that it transforms the inside of the human body into an inner landscape.

Taken as a whole, it teaches one grand technique of energies returning to their source. At the same time, each image scenario is a distinct meditation technique. For example, at the heart level the meditator is instructed to perform an archaic dance, the Pace of Yu, in order to walk the Big Dipper and so to collect heavenly energies. Instead of a spine is placed an upward flowing waterfall, pumped from the ocean of energy in the lower generative energy field of the body, to co-mingle with the body’s energy, and finally the energy of the mind in the upper energy field. The body becomes a landscape full of esoteric secrets. The meditator becomes a traveler returning to the Tao, the source of all things.

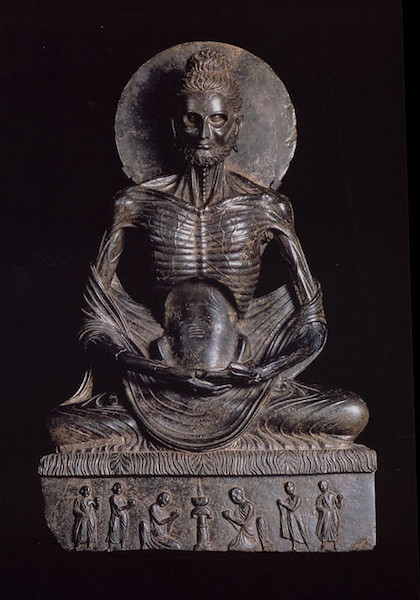

Fasting Buddha, Gandhara, second or third century.

Image courtesy of Lahore Museum

Much can be said about this famous sculpture of the fasting Buddha in the Lahore Museum. It is understood to be Shakyamuni Buddha at the end of his austerities sitting under the Bodhi tree, moments before he attained sublime transcendent enlightenment. Although seated in a canonical posture of meditation, serenity is not the salient emanating quality. The severity of the physical form is not at all about itself, but about the all-encompassing enlightenment to follow. The body is transcended, but not dishonored. The subject is what is to come. The body is skillful means.

This brief and cursory survey of images, intended to prime our minds with notions of the body, is offered so we can better understand in the next installment of this short series how Buddhist and Taoist notions of the body encountered one another, informed each other, and thoroughly integrated. In conclusion, please enjoy this little tale about the Fasting Buddha, from the village of Tabo, home to the oldest operating monastery in India, in the remote western Himalaya. Somewhere in a sutra someplace, it says something like this:

Once there were some people who did not believe Buddha was real. They could not accept that he was an actual person, made of bones, with blood flowing through his veins. In the midst of his fasting and austerities under the Bodhi tree, the Buddha showed himself to these people, saying, “See? I am made of bones. See? I have blood flowing in my veins.”

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Immortality and Invincibility, Part One: The 108 Luohan System