FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

Integrating Dharma Practice in Spanish: An Interview with Venerable Dhammadīpa Samaneri

Venerable Dhammadīpa was originally interviewed for Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that interview.

The Venerable Dhammadīpa Samaneri, also known as the Reverend Konin Cárdenas, is a Buddhist nun ordained in both the Zen and Theravada Buddhist traditions. The name Dhammadīpa can be broken down into its constituent words, where “Dhamma” means “the Buddha’s teachings” and “dīpa” refers to an “island,” a “light,” or a “lamp.” Therefore, the Pāḷi name of Rev. Konin Cárdenas—Dhammadīpa—means that she herself is an island who continues bringing people the Buddha’s light of wisdom, in this case to the United States and other parts of the world.

Ven. Dhammadīpa resides at the Aloka Vihara Forest Monastery in Placerville, California, and teaches Buddhism in English and Spanish. She became an interfaith chaplain and has completed four units of Clinical Pastoral Education. As a chaplain, she provides spiritual guidance at hospitals and hospices. Ven. Dhammadīpa earned an MBA from the University of California, Berkeley, and worked in finance for many years before she became a full-time Buddhist practitioner. This month, Buddhistdoor Global interviewed Ven. Dhammadīpa to learn about her life, practice, and future plans.

Ven. Dhammadīpa Samaneri. From dhamma-dipa.com

Buddhistdoor Global: We would love to hear a little about your life before you were ordained. Can you tell us what inspired you to become a Buddhist nun?

Venerable Dhammadīpa Samaneri: I began meditating in the Zen tradition in 1987, when I read the book Taking the Path of Zen by Rōshi Robert Baker Aitken. At that time, I felt how the bell must feel when we ring it: completely resonating. I was happy as a lay practitioner, mother, wife, and finance professional. So when I went to the San Francisco Zen Center in 2003, I had already been practicing Zen for many years. It wasn’t long before I started to study under Rev. Shosan Victoria Austin, my teacher in the United States who years later gave me Dharma transmission. I also participated in a study group, contemplating a book written by Rōshi Sekkei Harada, the abbot of Hosshin-ji, a Soto Zen training monastery in Japan. My friend, Rev. Daigaku Rumme, who coordinated the group, invited me to travel to Japan to sit a sesshin (an intensive meditation retreat) with Rōshi in May 2006. I had five encounters with Rōshi during that retreat, and I realized that the Dharma was much more vast than I previously thought.

Thanks to this profound experience, and the good example of Rev. Shosan, my ardor for practice burned even stronger. However, when I returned to the United States, I had many doubts about how to practice and about whether I was really capable of realizing such a great and wise Dharma. Yet, having found this gem, I couldn’t leave it behind. After discussing it with my daughter, I left my job and moved to Hosshin-ji in September of that same year. I wanted to become a nun because I wanted to invest my entire life in the Path, as my teachers had done, and I hoped I could support others, so that they too would have the opportunity to practice the Dharma.

End of the Jukai ceremony, giving the 16 precepts to student Dana Elliott, left, attended by Norma Fogelberg, right, at the Insight Meditation Center in Redwood City, California. Image courtesy of Martha Chickering

End of the Jukai ceremony, giving the 16 precepts to student Dana Elliott, left, attended by Norma Fogelberg, right, at the Insight Meditation Center in Redwood City, California. Image courtesy of Martha ChickeringBDG: What led you to devote yourself to disseminating the Dharma in Spanish in the US?

VDS: I spent approximately two years training in Japan and when I returned I was more aware of the effort other practitioners had made before me, so that the Dharma could be available in English. I decided that Spanish speakers could also benefit from the Dharma in their native language, so I decided to try to offer it myself. Also, when I experience the Dharma in Spanish, it touches me differently than in English. Different themes and feelings emerge. I imagined that others would feel the same.

BDG: Do you have followers from different Spanish-speaking nationalities?

VDS: Yes, there are several Spanish-speaking people who practice with me, both in person and online. Most are from Mexico and there are some from Spain, Brazil, and El Salvador. Some Americans who speak Spanish also attend.

Ayya Anandabodhi, left, Ayya Santacitta, middle, and Ven. Dhammadīpa, right, teaching at the Spirit Rock Meditation Centre in Woodacre, California. Image courtesy of Shannon Anderson

Ayya Anandabodhi, left, Ayya Santacitta, middle, and Ven. Dhammadīpa, right, teaching at the Spirit Rock Meditation Centre in Woodacre, California. Image courtesy of Shannon AndersonBDG: How do you conduct your teachings in Spanish and what formats do you use—online Dharma talks, blogs, in person?

VDS: I offer the Dharma in Spanish via my blog at www.dhamma-dipa.com, and I offer talks and retreats in Spanish in person and online. These teachings are normally recorded, so you can also watch videos on my website.

BDG: You are ordained in the Zen and Theravada Buddhist traditions. How did this dual lineage practice come about? Are there ways in which they are incompatible? Could you share your understanding with us of the standing of nuns in both traditions?

VDS: After practicing Zen for decades, I suddenly realized that although I am wholly committed to the Bodhisattva Path, I also appreciate the practice of the Vinaya. The Vinaya Piṭaka is one of the three “baskets” of the Pāli Canon, and includes the Patimokkha, the precepts that define the lifestyle of monastics in the majority of Buddhist traditions. We do not follow them in Zen. To me, practicing the Vinaya represents a further step in my commitment to invest all my energy and effort into living the Dharma. This is why I added the precepts of the Theravada to my Zen vows, and was ordained in the two traditions. The precepts of the Theravada may be the oldest in Buddhism. Such ancient wisdom inspires me.

I am living at a Theravada monastery and I am a Zen and Theravada nun. The traditions are compatible if we understand that Zen practice arose as a further development of the expressions of the Ancestors, which began with the teachings of the Buddha, our first ancestor in the Dharma.

There are difficulties for women in both styles of practice. In the Theravada tradition, nuns are more dependent on monks. One reason for this dependence is that, in modern times, both nuns and monks must gather for each ordination. This helps the folks who support the nuns to have confidence that the ceremonies are being performed correctly, but it also means that we cannot develop a lineage without the support of monks. I feel great, great gratitude for many of the Sri Lankan monks because they participated in all of the nuns’ ordinations I have seen in California, including mine. I believe that they feel responsible for helping because their national history is shaped by the arrival of Ven. Sanghamitta to Sri Lanka, who brought the lineage of Buddhist nuns from India. Conversely, many Western-born monks are opposed to the ordination of Theravada nuns because—in order to re-establish the lineage after 1,000 years without nuns—there were ordinations with only Theravada monks, or with Theravada monks and Mahayana nuns. Especially where I live, at Aloka Vihara, we nuns are developing a Vinaya lifestyle in the contemporary world while we continue to express the original intention of the precepts.

Ordination of Ven. Dhammadīpa as a samaneri in the Theravada tradition, at the Buddhi Vihara

Temple in Santa Clara, California. Image courtesy of Ven. Dhammadīpa

I had the good karma to find my master in Japan because, in general, nuns in Japan are not very highly valued. Today there are only two monasteries in the entire country where they can train, and the hierarchy of the tradition is completely dominated by monks. As an example of this, we need only look at the fact that the two main monasteries for the Soto Zen tradition in Japan are Eihei-ji and Soji-ji, and neither permits women to train there.

American Zen has made great progress in the equality of ordained women and men. There are many temples that are led by abbesses, and monasteries where women can train side by side with men. However, there have occasionally been people who were not mature enough to live in this kind of practice setting, and there have been cases of sexual harassment. In the end, society’s problems also manifest at temples and monasteries, just as they do in the secular world.

In both traditions, the aspiration is that people of any gender receive the same basic training and have the same opportunities to practice in healthy and safe locations. In the end, the most important thing is that women are enabled to devote themselves to a practice that leads to clarity, wisdom, and peace, whether it is monastic or lay. When you practice face-to-face with someone, whether it is a woman, man, or another gender, you will soon learn whether they truly understand this, and whether you truly understand it too. Because of this I feel great appreciation for Ayya Santacitta and Ayya Anandabodhi, with whom I practice at Aloka Vihara. These women truly understand this.

“Black Lives Matter, Because Love Matters” protest in Placerville, California.

Photo by Matt Weingast

BDG Could you tell us about your future plans? Do you have a personal Dharma mission?

VDS: I am in the process of writing two books. One of them describes the teachings that emerged from encounters during alms collections that support the monastics. The provisional title is Mendicancy in the Modern World. It will be a collection of stories about my experiences practicing in Japan and in northern California. These encounters, face-to-face with people who feel a deep sense of connection with the Buddhist community like I do, demonstrate the way in which each of us personifies the Dharma. I hope to have it ready by the end of the year.

The other book will be based on the teachings I offered in an online course to study the Heart Sutra. It will focus on the principle of emptiness and a skillful way to practice with the five aggregates and experience this principle directly. It was a request from one of my students, and I hope it will come out at the end of next year.

Ven. Dhammadīpa receiving her ordination in the Zen tradition at Hosshin-ji

in Obama, Japan. Rev. Fumai, left, and Rev. Kokyō, right.

Image courtesy of Ven.Dhammadīpa

I am also making plans to develop a small monastery for nuns and laywomen in Virginia, close to where my daughter lives. I hope there are people who appreciate the teachings of Buddhism in the way we nuns offer them. My intentions for the monastery are to:

• Demonstrate that profound practice on the cushion, and beyond the cushion, is always available.

• Explore the ways in which offering service to others creates greater intimacy with our common humanity and, in turn, honors the uniqueness of the one who is giving and the one who is receiving.

• Explore the ways in which the study of the Dharma brings us closer to the Buddhist community in the present, and allows us to experience the practices of those who lived centuries ago.

• Demonstrate that the arts and creative writing can reveal new expressions of the teachings of Buddhism, and reveal our unique ability to manifest beauty and wisdom.

I am sure we will need more places where we can meditate together once COVID-19 allows us to start meeting again. My personal Dharma mission is to invite everyone to practice with the broad Buddhist community, exploring how to live in beneficial service to others, while we awaken to the truly wise nature of the world and of ourselves. I hope that we all come to trust that we can progress together on the Noble Eightfold Path!

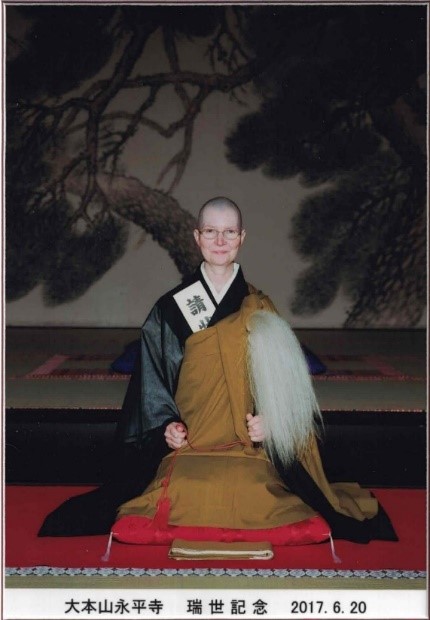

Photo taken at the end of the Zuise ceremony, during which Ven.

Dhammadīpa received the title of “Osho” (Venerable) and authorization

to be a sangha leader. Photo taken in Eihei-ji, the main Soto Zen

monastery in Fukui, Japan. Image courtesy of Nomoto Photo Shop

See more

About Venerable Dhammadīpa (Dhamma Dipa)

Audio Archives in Spanish (Dhamma Dipa)

Video Teaching Library (Dhamma Dipa)

Āloka Vihāra Forest Monastery

Teachings: Āloka Vihāra Forest Monastery

Programa de Dhamma en Español con Ven Dhammadipa (YouTube)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

From Hearts to Hearts: An Interview with Ven. Dhammananda Bhikkhuni

The 2,600th Anniversary of the Global Bhikkhuni Sangha and Fourfold Sangha of the Buddha

On Bhikkhunī Ordination by Bhikkhu Analayo: An Interview with Bhante Kusala

United by Our Common Vows: Tenku Ruff on Soto Zen in North America

Buddhistdoor View: Crisis and Opportunity for Theravada Buddhism

Buddhistdoor View: Supporting the Ordination of Theravada Bhikkhunis

Reflections from the 14th Sakyadhita International Conference: Nurturing the Theravada Bhikkhuni Sangha

Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project: The First Buddhist Nunnery in the UK

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

BBC Names Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, Thailand’s First Female Monk, among 100 Influential Women of 2019

Female Buddhist Monastics in Thailand Continue to Fight for Equality

Daughters of Buddhism in Thailand Find Growing Acceptance in the Face of Official Disapproval

Female Monastics in Thailand Barred From Paying Respects to Late King