FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhism in America (inactive)

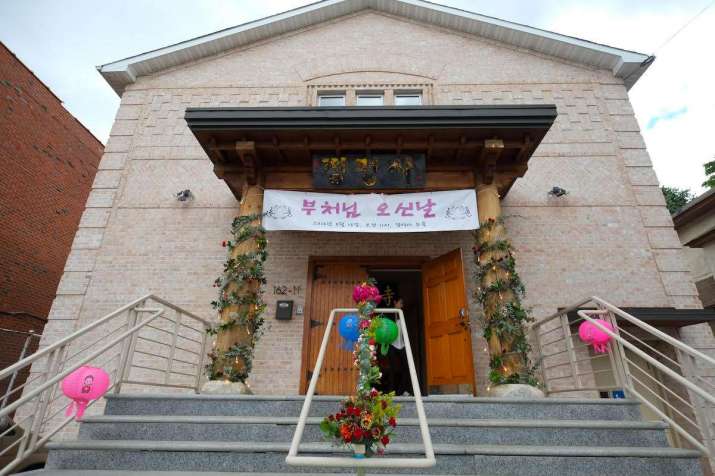

Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple: A Haven of Korean Buddhism in Queens

Do-Shin Sunim teaching in the main shrine hall on the temple’s first floor. Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple

Do-Shin Sunim teaching in the main shrine hall on the temple’s first floor. Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist TempleThe No.7 IRT Flushing Line on the New York City subway runs between the 34th Street–Hudson Yards station in Chelsea, and the Main Street station in Flushing, linking the boroughs of Manhattan and Queens, and providing transportation to thousands of New Yorkers who ride it daily. Traveling through diverse and cosmopolitan terrain, the last stop on the Queens-bound line is Flushing-Main Street at the corner of Main Street and Roosevelt Avenue.

The neighborhood of Flushing around this busy subway station seems to be in a constant state of change. Once home to Jewish and Italian immigrants, the area began to draw Chinese and Koreans from the 1980s onward.

“The first Korean immigrants worked in laundries, delis, nail shops, and restaurants, places like that,” said Do-Shin Sunim, the abbot of Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple, which was established in the neighborhood in 1995 to serve Korean Buddhists living and working in Flushing. The temple is located about a 10-minute bus ride from the Flushing-Main Street station.

In 1965, there was a tremendous change to immigration laws in the United States in the form of the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Celler Act, which abolished an earlier quota system that favored European Christians. This act motivated many Asians in particular to emigrate to the United States, bringing a multitude of religious traditions along with them.

Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple

Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist TempleAsian immigrants and others soon came to the United States so that they could be with previously arrived relatives, seeking an improved economic standing and to provide a better education for their children. Often leaving ethnically Buddhist homelands, they often faced hardship and discrimination while trying to become established. Many of these immigrants landed in New York City, and in Queens in particular. Today, one might say that the 7 train is a metaphor for the vibrant complexity of the American immigrant experience.

“Each stop on the 7 train in Queens now has a different temple,” said Do-Shin Sunim with a smile, referring to the different ethic neighborhoods along the line. He explained that once settled in the United States, many immigrants strove to establish places to practice their own religion—places that would both fortify them and connect them to their country of origin, and that would serve as places to acquaint their children with their cultural, linguistic, and religious heritage. Hence, Daoist, Hindu, and Jewish temples dot the landscape of Flushing, contributing to one of the most religiously pluralistic areas in the entire US.

It wasn’t always this way, the soft-spoken monk told me. In fact, the first Korean Buddhist immigrants to settle in Flushing had to travel some three hours by bus or car all the way to Wonjuska Monastery in the Catskill Mountains, as there were no nearby Korean Buddhist temples in the 1980s. Such travel would take time away from family and work, yet members of the Korean community persisted in their earnest desire to practice.

“It’s very have to be hard to be a Buddhist living in America,” the monk told me, as he narrated the story of how Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple came to be. It turns out that a Korean Buddhist monk by the name of Gil-Sang Sumin, who was staying at Wonjuska Monastery in the Catskills, was very moved by the diligence and sincerity of those who made the three-hour journey from Queens to practice and connect with their Buddhist identity.

The founding of the temple. Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple

The founding of the temple. Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist TempleWonjuska Monastery is affiliated with the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism, the largest Korean Buddhist order in the world. Comprised of some 20,000 monks and 20 million lay Buddhists, the order’s history can be traced back some 1,200 years.*

Out of compassion for the Korean Buddhist immigrants of Queens, Gil-Sang Sumin had a vision of establishing a temple to serve them. He soon devoted himself full time to this endeavor, coming to Flushing to make this vision a reality just over 20 years ago. Today, Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple is a refuge for community members, who meet regularly each Sunday morning at 11am for a service that consists of reciting the Chun Su Kyung Sutra, bowing, reciting the Buddha’s name, reciting the bodhisattva vow, and concluding with a Dharma talk. There is also a children’s service on Sunday mornings from 10:30am.

In addition, the temple has daily morning prayers and celebrates numerous Korean Buddhist holidays, such as the Buddha’s birthday, based on the Chinese lunar calendar and therefore celebrated in late April or early May. Also celebrated is a festival known as Baek-Jung, a form of ancestor worship lasting 49 days. Baek-Jung, also known as the Ghost Festival, is said to have crossovers with Indian Buddhism. Chuseok, also based on the Chinese lunar calendar, is celebrated, and Do-Shin Sunim explained that it is similar to the American Thanksgiving. Winter solstice, known as Dongjing, is also observed, as is a day in or around February that Koreans believe marks the end of winter and the beginning of spring, known as Yp-Chun. Finally, the traditional New Year based on the lunar calendar is also celebrated.

Since the abbot is a yogi, Jungmyungsa offers classes in yoga asana on a weekly basis. Having spent time in southern India in serious yoga practice, Do-Shin Sunim feels that yoga classes offer a way to broaden the temple’s appeal. Do-Shin Sunim is also a scholar who first came the US to study Buddhism, attracted by “academic studies in general and Buddhism in particular.” He says that he was drawn to what he was told would be a more experimental nature of education in the US. Upon meeting Gil-Sang Sumin in Korean in 2008, he accepted an invitation to come on a religious visa to the United States in 2010.

Second floor. Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple

Second floor. Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist TempleWhile serving at the temple, this dedicated scholar-monk was able to earn a Bachelor of Arts in Comparative Religion at Manhattan’s Hunter College, where he traveled daily for classes back and forth on the 7 train. Further curiosity and academic excellence led him to attend Harvard Divinity School, where Do-Shin Sunim recently graduated with a master’s degree in theological studies, with a focus on Buddhism.

Out of a desire to honor the temple that sponsored him, he moved back to Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple after graduating from Harvard. Do-Shin Sunim is currently interested in pursuing a Phd in the New York area so that he may continue his university education while serving the temple’s community.

Do-Shin Sunim tells me feels the temple members bear a “double burden,” in that not only do they have the challenges faced by immigrants to a new country, they are also a minority within the Korean immigrant population. “Almost 90 per cent of Korean immigrants in the US are Christian,” he offered. “It is critical to support Korean Buddhists because they face intense conversion efforts.” There is also discrimination in the form of Buddhist children being teased at school, and even business boycotts. “So life for them can be difficult,” he said.

Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple

Image courtesy of Jungmyungsa Buddhist TempleBegun with the compassion of a monk living in the Catskill Mountains, the urban Korean Buddhist temple of Flushing, Queens, known as Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple may be small in size but is magnanimous in significance. Upholding traditional Korean Buddhism, the temple continues today to be propelled by the current abbot’s strong and sincere effort to serve the Buddha, his order, and the Korean Buddhist community of New York. In an act of generosity, Do-Shin Sunim aspires to provide a home “for all people living in Queens and other neighbors.”

Just as the dreams of countless immigrants have been to grow, prosper, and flourish in the US, may the same happen for Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple, at the end of New York City’s No.7 subway line.

* Jogye Order (Wikipedia)

See more

Jungmyungsa Buddhist Temple

Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

From Seoul to Somerville: The Founding of a Korean Won Buddhist Temple in Massachusetts

The Meditative Mosaics of Lee Kwanwoo

Seon and the City