I arrived in Songgwangsa (one of the oldest Seon, or Zen, temples in South Korea) in 1975 on the first day of the biggest ceremony of the year, the commemoration of the death of national master Bojo. The next morning, Haemyong Sunim (Robert Buswell) took a young American who had recently arrived, Larry Martin (who became Hyunsung Sunim), and myself to see Venerable Kusan Sunim, the renowned master of the temple. I had never met a Zen master before, and went with great trepidation. We paid our respects by bowing three times as instructed, and then sat and waited. He smiled warmly.

First, he asked us where we had come from and our nationality. Then, with a penetrating gaze, he looked at me and said:

“What is the most important thing in the world?”

I replied: “Two people smiling at each other.”

He smiled: “Yes, that’s good, but there is something even more important than that. You know your body, but do you know your true mind?”

I could not answer.

He then proceeded to encourage me to meditate by asking myself at all times: “What is this?”

Then he turned to the young American and said:

“What is the most frightening thing in the world?”

“To walk alone in the dark at night.”

The master laughed heartily: “No, there is something much more frightening than that—not to know your own mind.” He then gave him the same question to investigate: “What is this?”

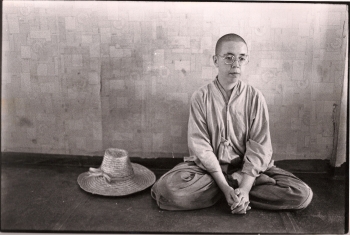

So impressed was I that over the next three days I decided to become a nun. Up to then I had not sat in meditation for very long, nor did I have any idea what Buddhist nuns actually did. Nevertheless, I made up my mind and immediately told Ven. Kusan Sunim. He seemed pleased, and straight away began to consider which of his nun disciples could serve as my preceptress.

My preceptress and Ven. Kusan Sunim agreed that it would be best if I stayed at Songgwangsa for the meditation season. I could practice with two other Western women who had recently arrived, work in the kitchen, and learn Korean. Whenever necessary, I could talk to Ven. Kusan Sunim with the help of a translator. It was a great opportunity, although I was rather anxious since I had never really meditated before.

One day, Ven. Kusan Sunim came to meditate with us. I diligently applied myself to my hwadu, moving only occasionally on the cushion, but after that I could not face another hour and left. Upon my return, the monk-in-charge approached me, dictionary in hand. Ven. Kusan Sunim had asked him to tell me to “okchiro ch’amda”! We pored over the dictionary together. It meant “to bear beyond strength.” I took a deep breath and promised to mend my ways. These words were among the first I learned in Korean. I’ve never forgotten them.

Ven. Kusan Sunim used to tell us that we should work with our hands, but with our mind, we should keep investigating the hwadu. He used to encourage us not to succumb to confused states of mind. If the practice did not go well, one should not be sad, and if the practice did go well, there was no reason to be especially joyful. He emphasized the cultivation of patience and endurance. These would then help us develop tranquility and enquiry.

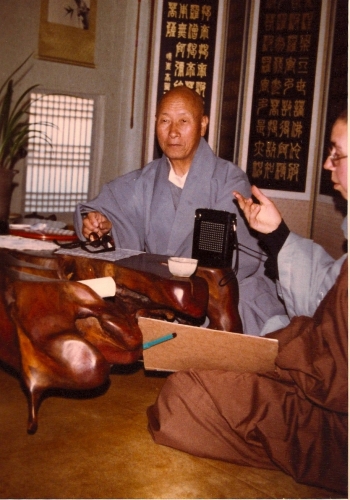

Often Western students of Japanese Zen Buddhism would come to visit, and I would translate during their meeting with Ven. Kusan Sunim. He would try to check their understanding by asking them: “What is it?” Some of them would push a cup towards him, or babble or give a shout. Then he would ask: “Before you move the cup, before you babble, before you shout—What is it?” None of them could answer. It seemed that he was trying to direct them towards the essence of things rather than remaining caught up in traditional gestures and responses.

Once, while we were on our way to the fields to work, I was waiting with a Western monk and Ven. Kusan Sunim for some tools to arrive. The German monk took the opportunity to tell Ven. Kusan Sunim of his difficulties in keeping the hwadu, especially when working. Ven. Kusan Sunim said that for himself, he was able to maintain the hwadu all the time. The German monk exclaimed: “But why should you need to work on a hwadu once you are enlightened?” Pangjang Sunim said: “As the practice evolves, the hwadu also evolves. I still use a hwadu, but in a different way.” The German monk asked him how he did it now as opposed to before. But the master refused to reply, pointing out that any explanation would be meaningless and concepts about it would only be a hindrance to real enquiry.

After the bimonthly lecture (popmun) was over, the foreign monks and nuns would follow Ven. Kusan Sunim up to his room. I would translate what he had said, and then he would answer questions and give us tea. Sometimes he would catch us out as we drank the tea. After the first sip he would ask: “Does it taste good?” We would answer: “Oh yes, it's very good.” Then he would say: “What is it that tastes the tea?” Everyone would remain silent.

In June 1983, Ven. Kusan Sunim’s health began to deteriorate. His eyes and his ears began to trouble him, and this affected his balance when walking. To remedy this condition he decided to exercise by working in the fields. Since the nuns’ compound, Hwaeumjon, was on the way to the fields, he would often stop by and ask me to join him. Once there, we would pick stones out of a field or cut the blackened, diseased heads of the barley. He would sometimes call out to me and ask me about well-known koans, for example: “What did Chao-chou mean by ‘the cypress in the courtyard’?” I would reply that I did not know. He would stress that I should awaken to the meaning of this by practicing diligently. Then we would rest by the side of the field and he would tell me Zen stories.

On another occasion, I accompanied him and his attendant for a walk. At one point we stopped and sat on a tree trunk. He said: “No matter how much you have practiced, you are never sure how you are going to be at the moment of death. You must practice diligently all the time, to be as well prepared as you can.” This great and humbling Dharma teaching touched me deeply.

I left Songgwangsa and disrobed in 1985. But the teaching of Ven. Kusan Sunim has never left me. I still endeavor to put it into practice and teach it to others. Not a day goes by that I am not grateful for the training and guidance I received from Ven. Kusan Sunim.

Martine Batchelor is a Buddhist writer and lay meditation teacher. She was a nun in South Korea for ten years, from 1975 to 1985. Some of her latest books are: Meditation for Life, Let Go, and The Spirit of the Buddha. This article is the first in a three-part series on the author’s life as a nun in Korea.