FEATURES|COLUMNS|Ancient Dances

Mario Fantin: Mountaineers, Ethnography, and Buddhism

Mario Fantin, 1964. Self-portrait

Italy has a patrimony of mountaineering, and of Buddhist research in Tibet and the Himalaya. These don’t always intersect, and sometimes do. Ethnography is something shared by both disciplines, often unbeknown to the other. Understood as a scientific account describing the customs of distinct cultures and peoples, ethnography takes many forms and has been produced by many different types of professionals and scholars.

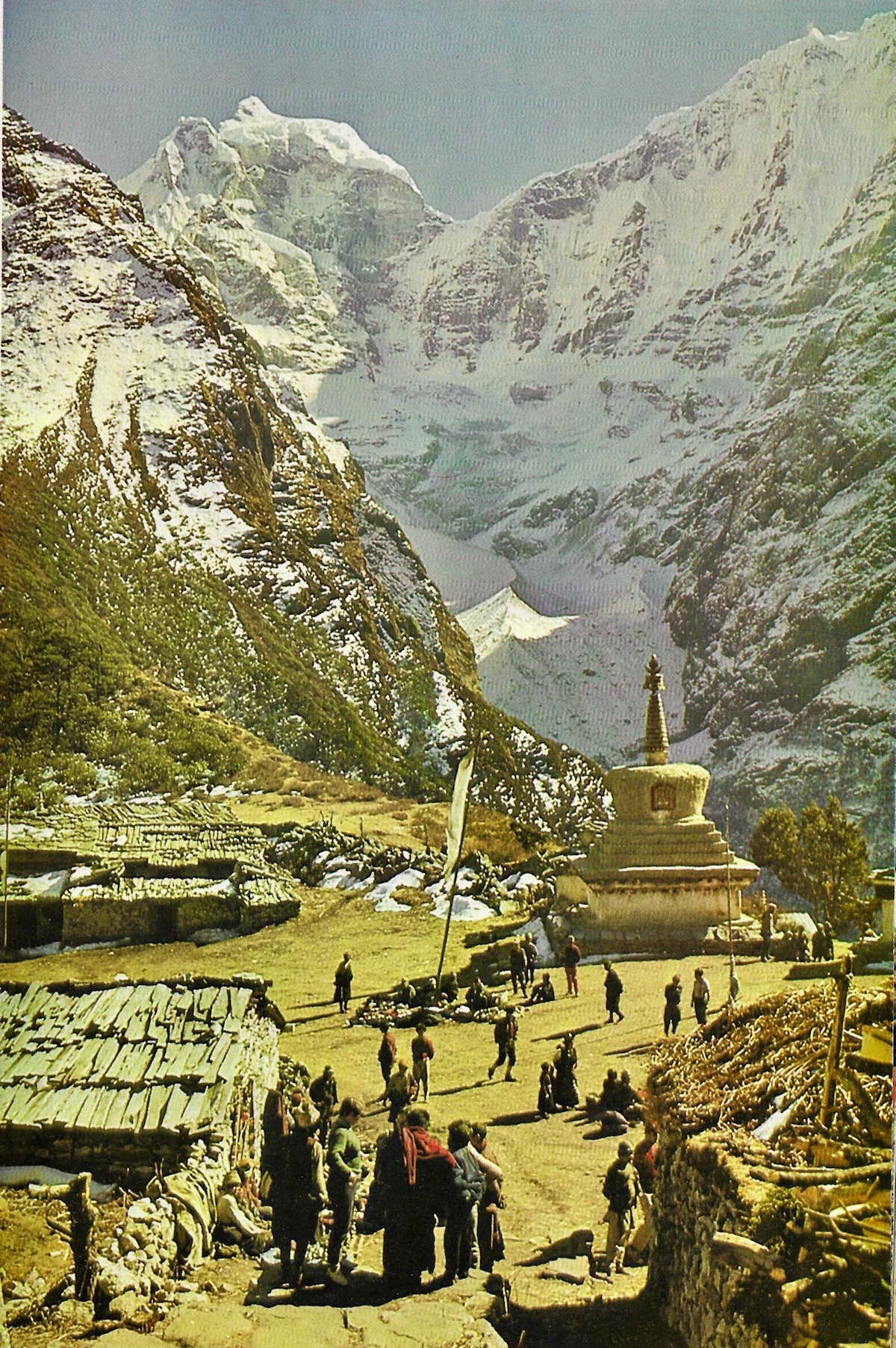

Nepalese landscape. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama

of Tengboche (1976). Photo by Mario Fantin

Painters Urjingiin Yadamsurem of Mongolia and Tyra Kleen of Sweden were ethnographers of Buddhist ritual dance. Joseph Rock, an Austrian-American botanist, was an ethnographer of Buddhist dance. Claire Holt, the Latvian-born art historian, was a dance ethnographer of Buddhist, Hindu, and indigenous dances of Indonesia. Werner Forman, the German anthropologist and photographer, was an ethnographer of Mongolian Buddhist dance masks. Swede Sven Hedin was a cartographer, and ethnographer of Tibetan dance. These are a few admirable examples of ethnographers of different stripes whose methods continue to inform us.

Not only are the methods of each of these ethnographers revealing, but also the individuals themselves. Ethnographies of ancient dances are things to be discovered in used bookstores and expansive old libraries. Mario Fantin (1921–80) was an Italian mountaineer of some distinction. Part of the Italian mountaineering team of 1954 that victoriously summited K2, Mario Fantin climbed mountain ranges and peaks on every continent. At 8,600 meters, K2 is the second-highest summit in the world, and Fantin considered it the most treacherous.

Footage from first conquest of K2, 1954, by Mario Fantin

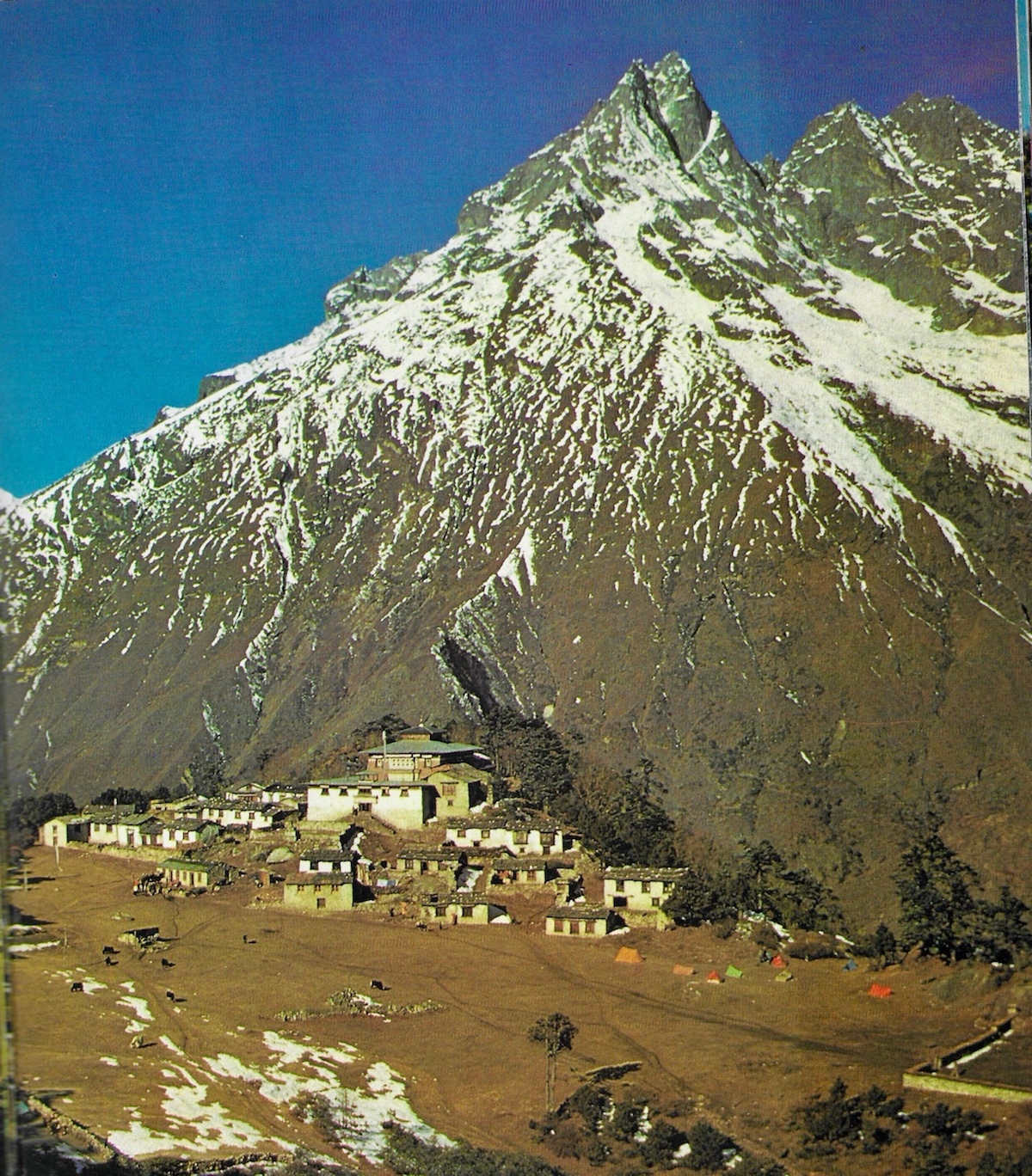

With Mount Everest now a sorry money-spinner and a victim of ecological sacrilege, it is harder to imagine a time when no one, or very few, had summited that sacred peak. Special permits were required to enter the area and the Sherpa people, much admired throughout the Himalaya and the world, were viewed as a culture rather than a workforce. In 1969, Fantin walked from Kathmandu to the Sherpa villages at the base of Mount Everest, where he discovered the Sherpa society and became a great admirer of Tengboche Monastery.

The Stupa at Tengboche Monastery. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist

Dance Drama of Tengboche (1976). Photo by Mario Fantin

It was there that he just missed the Mani Rimdu Buddhist dance ceremony at Tengboche Monastery, and so Fantin returned twice more to document the festival after writing his book, Sherpa, Himalaya, Nepal in 1971. He calls that book “a monongraph.” That is the same term he uses to describe his dance ethnography Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama of Tengboche, written in 1976. For Fantin, the amazing, never-before-seen dances were not obscure: they were clearly a grand drama playing out.

Tengboche Monastery. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama

of Tengboche (1976).Photo by Mario Fantin

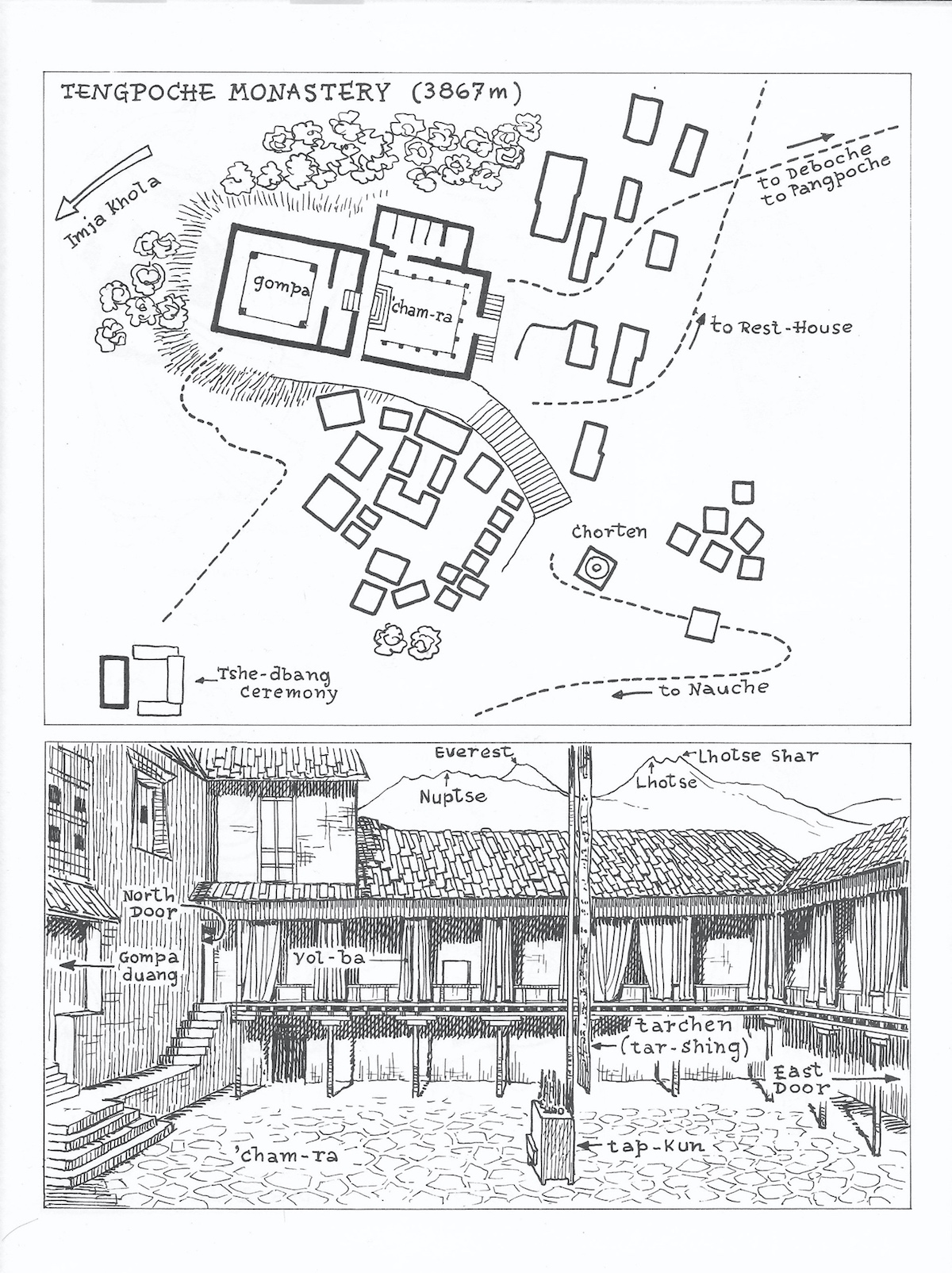

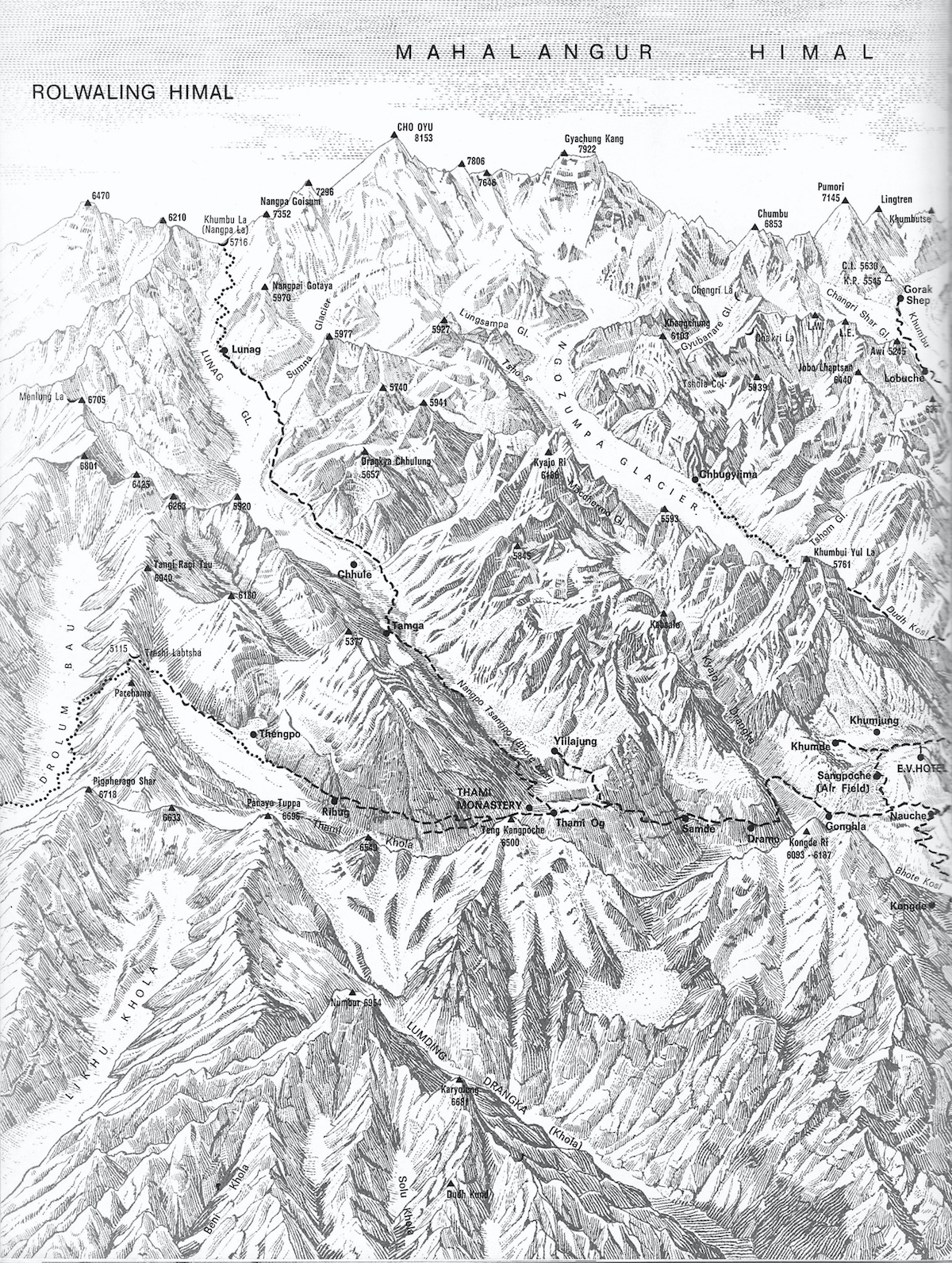

In seeing these as monographs: single-subject portfolios, a topic explored in depth, we see Fantin’s beautiful method. He has elements in common with Tyra Kleen in numbering images and using their sequential descriptions and explanations as the core text of the monograph. He has elements in common with master cartographer Sven Hedin, in the creation of excellent and beautiful maps. And he has elements in common with Claire Holt in producing volumes that are “all-in-one”—including maps, diagrams, photographs, drawings, scientific accounts of the mountains, environment, and architecture. The document includes glossaries, costumes, masks, instruments, and text. These are replete choreological records bound together in one document, produced by a man who walked from Kathmandu to Mount Everest.

Hand-drawn map of Tengboche Monastery and drawing of the dance

courtyard, chamra. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama

of Tengboche (1976). By Mario Fantin

These books are marvels of self-representation, with Fantin producing every element. The Mani Rimdu book is the reflection of an orderly mind. First, it is beautiful. Fantin understood and cared about beauty. It is a well-made book, physically and conceptually. He begins with an introduction to Nepal such as only a mountaineer could provide. He describes religious ethics and significance, and is humbled by Buddhism, which he conveys with a deep reverence and a concern for accuracy. Fantin believed that culture belongs to a place, and place belongs to a landscape. This is followed by an introduction to the Mani Rimdu festival and its mystical significance. This is followed by the festival’s program of the 13 dances presented. These dances are named according to the names of the deities dancing.

The Protector God of the Khumbu region. From Mani Rimdu Nepal,

the Buddhist Dance Drama of Tengboche (1976). Photo by Mario Fantin

Fantin then proceeds to itemize 109 sequential photographs, each providing in the photo an image to describe a particular phase of the dance. The elaborate descriptions of 109 photos are interrupted with the 109 photos themselves presented as a single, central portfolio of images. This choice provides much continuity as an account of what Fantin did, and how the whole story is bigger than the sum of the photos. The photos are presented as both an artistic and scientific accomplishment.

The photos are followed by a section of eight pages of hand-drawn maps. This is followed by a 62-page glossary of mostly Buddhist and dance terms. This perfect book concludes with a section of Fantin’s hand-drawn renderings of the dance courtyard, the costumes, instruments, and implements, including serving utensils such as teapots and candle lamps.

Hand-drawn documentation of Cham costumes, with elements identified.

From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama of Tengboche (1976).

By Mario Fantin

Fantin conducted more than 35 mountaineering trips outside of Europe. He wrote ethnographic monographs of mountain cultures in the Andes, the Sahara, and elsewhere. His method provides us today with a rigorous account of his actions, scientific by their ordering. Fantin devised an enriching ethnographic formula that facilitated and fit in well with his first love, mountaineering. Some work needed to be completed in the field. Other work could not be completed until a return to Italy. Yet it is all intended from the start to produce a single monongraph.

Black Hat dance. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama

of Tengboche (1976). Photo by Mario Fantin

Mario Fantin’s archive of more than 300,000 photographs is maintained at the Italian Alpine Club in Turin. From the late 1950s onward, for nearly 20 years, Mario Fantin produced a book and a film almost every single year, and sometimes more than one per year. It is extraordinary, full of this man’s joy for life. His work is not easy to locate or access. It would be a good thing if his complete body of mountaineering ethnography were made available to an admiring posterity. A mere four or five films are available commercially, yet there are so many more. He clearly was a self-actualized man. These monographs and films are the record of a fine life.

Ging-pa. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama

of Tengboche (1976). Photo by Mario Fantin

Mountaineering has been so often befuddled with scandals around glory and conquest, even by relying on words such as “conquering” and “victory.” Fantin rather escaped this measure of things through his self-created way of mountaineering ethnography, including the making of ethnographic films. His works are difficult to find today and yet they remain a baseline of 20th century mountaineering ethnography. They are real measures of a man in full stride, who measured everything he did. Leaving for posterity comprehensible accounts of vanishing worlds, these books shine with the awe that Fantin experienced in his own travels through life.

Hand-drawn mountain map. From Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance

Drama of Tengboche (1976). By Mario Fantin

References

Fantin, Mario. 1971. Sherpa, Himalaya, Nepal. New Delhi: The English Book Storei.

———. 1976. Mani Rimdu Nepal, the Buddhist Dance Drama of Tengboche. New Delhi: The English Book Store.6ri

See more

Mario Fantin (IMDB)

Core of Culture

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Nicholas Roerich: Master of the Himalaya

Pioneering Himalayan Buddhism in the US: The Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art

Finding Excellence, Part 1: Of Course They Don’t Talk About It

Finding Excellence, Part 2: A Tradition of Transmission

Finding Excellence, Part 3: Who is the Best Dancer Here?

Finding Excellence, Part 4: What Buddhists Do

Finding Excellence, Part 5: A Buddhist Land

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Renowned Buddhist Lama Ngawang Tenzin Jangpo Rinpoche Dead at 85

Mt. Everest Visible from Kathmandu for the First Time in Decades as COVID-19 Lockdown Clears Smog

Growing Mountains of Litter Plague the Tibetan Plateau

Buddhist Monk Who Blessed Mount Everest Climbers Passes Away